« October 2006 | HOME PAGE | December 2006 »

November 30, 2006

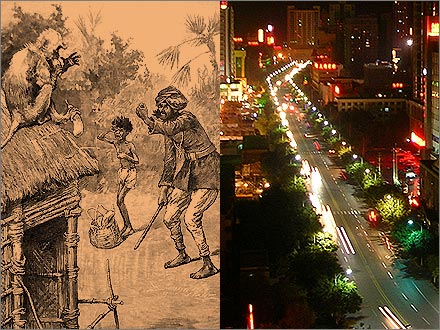

Xinjiang's War on Drugs

China's battle against illegal substances seems to going about as well as the United States' own "War on Drugs", which has been raging for more than 20 years now. That is, not very well. Here in Xinjiang, where opium and heroin flow over the borders with Pakistan and Afghanistan, rates of drug use are higher than ever. Police estimate that the consumption of heroin in Urumqi has risen by more than 600% since 2000. Of course, the newspapers here try to publish upbeat reports, but by connecting the dots you can see that things really aren't going so well.

China's battle against illegal substances seems to going about as well as the United States' own "War on Drugs", which has been raging for more than 20 years now. That is, not very well. Here in Xinjiang, where opium and heroin flow over the borders with Pakistan and Afghanistan, rates of drug use are higher than ever. Police estimate that the consumption of heroin in Urumqi has risen by more than 600% since 2000. Of course, the newspapers here try to publish upbeat reports, but by connecting the dots you can see that things really aren't going so well.

First, from China Daily:

In the first nine months of this year, local police in Xinjiang's capital city Urumqi had 16 trafficking cases involving drugs from Afghanistan and Pakistan, almost double the same period last year.

Police estimated the annual consumption of heroin in Urumqi grew from 1 ton in 2000 to 7 tons, and said more drugs are being transferred from Xinjiang to other Chinese cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, as well as Russia and Eastern Europe.

Now, a story from SBS World News:

Local police in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region announced yesterday that 27 drug trafficking suspects from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Africa had been captured so far this year.

Police in Xinjiang said they'd arrested the suspects in connection with 13 major cases involving multi-national drug trafficking. Police have seized 53.1 kilograms of heroin, almost triple the amount for last year, stated a press release provided by the region's Public Security Department over the weekend.

So, let's see... 53.1 kilos over 7,000 total kilos, carry the one, multiply by one-hundred... and you get a decent idea of the success rate of Xinjiang's War on Drugs: 0.75%, or less than 1 out of every 130 kilos coming across the border.

But never mind that, I'm sure things will turn out fine in the end... after all, Urumqi's police department has erected a quadripod in the city honoring the "International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking", which apparently falls on June 26th. What's better, the quadripod sits next to a statue of Lin Zexu, China's drug control pioneer (see Opium War):

Lin (1785-1850) was honored as the first Chinese who fought against drugs. On June 3, 1839, he ordered the destruction of about 1,000 tons of smuggled opium confiscated from British and American merchants, at Humen in south China's Guangdong Province.

In 1842, Lin was sacked and sent into exile in Xinjiang because the government bowed to aggressors.

And so you see, it all comes back to Xinjiang. You can read the full articles below.

Neighbours to intensify drug crackdown

Zhu Zhe

25 November 2006

China Daily - Hong Kong Edition

China will step up co-operation with Pakistan to fight increasing drug trafficking from the "Golden Crescent" region into Northwest China, according to the Ministry of Public Security.

Senior officials from Pakistani drug prohibition departments will visit China this year for closer bilateral co-operation, the ministry said in a report on its website on Wednesday.

The efforts will boost an already intensified crackdown of the trans-national drug trade by the two countries, resulting in a number of trafficking cases in the past year.

The report said drugs produced in the Golden Crescent region, encompassing the mountain valleys of Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, pose a growing threat to China, especially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Opium cultivation in Afghanistan rose to 165,000 hectares this year, and an unprecedented 6,100 tons of opium was harvested, said the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime this September.

About 70 per cent of Afghanistan's drugs are trafficked through Pakistan. Xinjiang, a region that neighbours Pakistan, has become one of the major areas for drug flow, according to a report by the International Herald Leader under Xinhua.

In the first nine months of this year, local police in Xinjiang's capital city Urumqi had 16 trafficking cases involving drugs from Afghanistan and Pakistan, almost double the same period last year.

Police estimated the annual consumption of heroin in Urumqi grew from 1 ton in 2000 to 7 tons, and said more drugs are being transferred from Xinjiang to other Chinese cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, as well as Russia and Eastern Europe.

"China faces a serious threat from drugs from the Golden Crescent region," said Chen Cunyi, deputy secretary general of China's National Narcotics Control Commission at a news conference in June. "To better fight against drugs, we need to have more international co-operation."

China started anti-drug co-operation with Pakistan in 1996 when the two counties signed a memorandum of understanding on drug prohibition.

The countries say the partnership has been strengthened in recent years.

The Ministry of Public Security said Pakistan intensified its airport security checks this year and seized a large amount of drugs headed to China. China's anti-drug efforts in the past year resulted in several trans-national drug trafficking cases, the ministry said.

September 17, police in Southwest China's Yunnan Province broke a drug trafficking ring, seizing 13 suspects and 430 kilograms of drugs.

Co-operation with police in the United States and the United Arab Emirates also helped break a major drug ring July 31, in which two foreign suspects were arrested and 2 kilograms of heroin seized.

China has also launched opium replacement planting schemes in the "Golden Triangle" region, an area along the Mekong River Delta including Myanmar and Laos. Rubber, tea and other cash crops have been grown as substitutes.

Due to Chinese and international efforts, opium poppy cultivation in the region has dropped to 24,160 hectares this year, down 85 per cent from eight years ago, the ministry said.

Heroin 'pouring into China'

14 November 2006

SBS World News Headline Stories

Local police in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region announced yesterday that 27 drug trafficking suspects from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Africa had been captured so far this year.

Police in Xinjiang said they'd arrested the suspects in connection with 13 major cases involving multi-national drug trafficking. Police have seized 53.1 kilograms of heroin, almost triple the amount for last year, stated a press release provided by the region's Public Security Department over the weekend.

Police attributed the "spike" in drug-smuggling cases to a significant increase in production in the "Golden Crescent" area, which is currently the world's leading source of drugs. The area straddles the common borders of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.

In 1999 the area produced 4,600 tons of opium or about 75 percent of the world's total output that year, making Afghanistan the world's top opium producer. This year, by comparison, Afghanistan is expected to produce 6,100 tons of opium or 92 percent of the total global output.

To prevent drugs from the "Golden Crescent" arriving in China, local public security departments have reinforced their staff and toughened inspection procedures along the frontier as well as at customs bureaus, storage depots and major points along air routes and roads.

On October 22, customs officers found 20.7 kilograms of heroin in powder form hidden in 10 boxes marked "date fruits" that two Pakistan businessmen were carrying. That discovery represented the largest seizure of illegal drugs in Xinjiang. To date nine suspects have been arrested in connection with the case including six Africans and three Pakistanis.

Quadripod erected in Xinjiang as anti-drug symbol

Xinhua News Agency

June 25, 2004

A bronze quadripod was erected on Thursday beside the statue of Lin Zexu, China's drug control pioneer, in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwest China.

A bronze quadripod was erected on Thursday beside the statue of Lin Zexu, China's drug control pioneer, in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwest China.

According to local officials in charge of the drug control, the quadripod was built to observe the International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, which falls on June 26.

Quadripod is a sacrificial vessel used in ancient China which evolved into a symbolic ritual article to commemorate major events nowadays.

Local government planned to build an anti-drug educational basearound the statue and the quadripod to arise public awareness of the harm brought by drug-taking, officials said.

Lin (1785-1850) was honored as the first Chinese who fought against drugs. On June 3, 1839, he ordered the destruction of about 1,000 tons of smuggled opium confiscated from British and American merchants, at Humen in south China's Guangdong Province.

In 1842, Lin was sacked and sent into exile in Xinjiang because the government bowed to aggressors.

posted November 30, 2006 at 03:26 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (43)

November 26, 2006

Frank Nicholas Meyer's Xinjiang

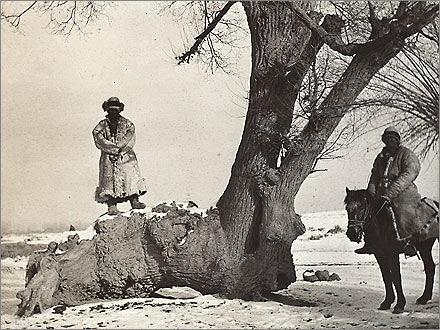

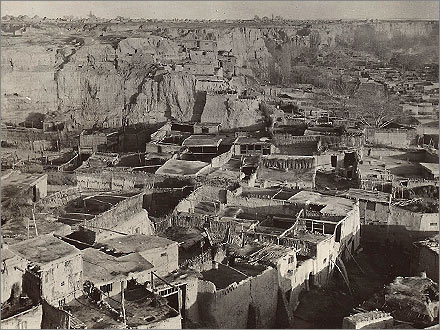

Frank Nicholas Meyer, a Dutch botanist who immigrated to America in 1901, quickly found employment with the US Department of Agriculture's (USDA) Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction. They sent him off to East Asia where he was to collect samples of "trees and shrubs of ornamental value" and take photographs of local plants and landscapes. Thus, Meyer passed through Chinese Turkestan - now Xinjiang - in the winter of 1910/11, shooting what are the earliest photographs I've yet been able to find of the region. Luckily, Meyer wrote captions on the back of his photographic prints, forever immortalizing his opinions and observations of the locales he visited. For the most part, he writes straightforward and mildly interesting comments like:

Frank Nicholas Meyer, a Dutch botanist who immigrated to America in 1901, quickly found employment with the US Department of Agriculture's (USDA) Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction. They sent him off to East Asia where he was to collect samples of "trees and shrubs of ornamental value" and take photographs of local plants and landscapes. Thus, Meyer passed through Chinese Turkestan - now Xinjiang - in the winter of 1910/11, shooting what are the earliest photographs I've yet been able to find of the region. Luckily, Meyer wrote captions on the back of his photographic prints, forever immortalizing his opinions and observations of the locales he visited. For the most part, he writes straightforward and mildly interesting comments like:

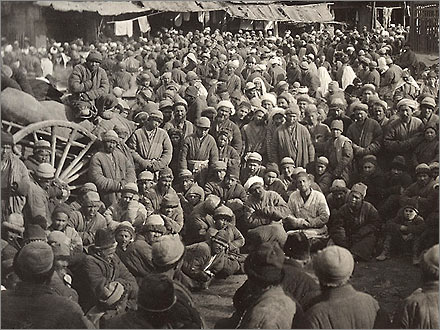

Every Friday, there is a large market or bazar held in Kashgar and every Sunday a small one. This picture shows the Friday market. Cloth, skins, rice, flour, dried fruits, and in fact, all sorts of things are sold and resold. Kashgar, Chinese Turkestan. February 9, 1911.

The real fun begins, however, when he starts commenting in the typically condescending (and often racist) tone common to Edwardian anthropological observations:

A business meeting of Sarts and Kirghiz in the courtyard of our inn. The farther one moves away from the coasts washed by cold, salt water the more stupid man becomes. The natives of Central Asia certainly are the essense of ignorance and unprogressivenesss. Kashgar, Chinese Turkestan. October 22, 1910.

The Friday bazar in Kashgar. A storyteller informs the crowd of former glories of Turkestan. The natives of Chinese Turkestan are known for their lying, lazy and cheating dispositions, combined with an intense ignorance. They are, however, not revengeful and murder is a very rare occurance. Kashgar, Chinese Turkestan. February 9, 1911.

Well, at least ol' Frank didn't beat around the bush. Below you'll find a few of Meyer's photographs from his visit to Xinjiang. Click on the small images below for higher resolution versions. These images and more can be found over on Harvard University's Visual Information Access system:

For a comparison with that last photo, here's a picture I snapped at Kashgar's livestock bazaar earlier this year:

posted November 26, 2006 at 02:59 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (23)

November 22, 2006

Sundried Tomato Interview

My favorite half-Asian female and longtime friend, Cathy Erway, has posted an interview with me and a few pictures of Demeter Foods' sundried tomato operation over at her excellent foodie blog, Not Eating Out in New York. The blog's title is derived from Cathy's pledge, now four months strong, to never eat out at a restaurant again. If you want to know more about what I'm doing here in Xinjiang — or if you just want to learn how to sun-dry a tomato for yourself — I suggest taking a look. The recipes are fantastic, too.

posted November 22, 2006 at 11:49 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (12)

November 21, 2006

The Federal People's Republic of China, circa 2036.

The musings of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) — which publishes analysis and forecasts on over 200 countries — are a fun read for those few people lucky enough to have access. Unlike it's conservative cousin, The Economist, EIU is chock-full of strange yet stimulating predictions about the future of the world we live in. EIU's excellent publication Business China (of interest to me for obvious reasons) has just celebrated its 30th anniversary with a special issue. The wrap-up of the past 30 years is interesting enough... China has certainly come a long way since 1976. But it's the lengthy set of predictions about the state of affairs in China 30 years from now that really hits the spot.

The musings of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) — which publishes analysis and forecasts on over 200 countries — are a fun read for those few people lucky enough to have access. Unlike it's conservative cousin, The Economist, EIU is chock-full of strange yet stimulating predictions about the future of the world we live in. EIU's excellent publication Business China (of interest to me for obvious reasons) has just celebrated its 30th anniversary with a special issue. The wrap-up of the past 30 years is interesting enough... China has certainly come a long way since 1976. But it's the lengthy set of predictions about the state of affairs in China 30 years from now that really hits the spot.

The editors at Business China boil down the major issues confronting China between now and 2036 to a single question: Will rampant pollution kill millions of Chinese in their prime, or will they be the happiest bunch of yuppies the world has ever known?

I'll post a few of the best predictions here for my lazy readers... but if you've got the time, do yourself a favor and read the full text below.

On foreign policy:

China’s troubled relationship with Japan is almost certainly headed for some sort of “settling of the score”. China’s deep distrust of and enmity with Japan stemming from the military conflicts of the 20th century have been compounded by Beijing’s suspicion that Tokyo has been abetting the independence movement in Taiwan, a former Japanese colony. More generally, given its insatiable demand for raw materials and natural resources to fuel its industrialisation, it is safe to assume that China will become more assertive in its backyard. That is why Beijing quietly dropped the use of the phrase “peaceful rise”. The reality is that rising big powers always bully small neighbours!

On politics:

In a more imaginative application of creative ambiguity, the province of Fujian will pioneer the use of “free trade investment zones” with their boundaries extending to include airports and ports in both Fuzhou and Xiamen. By thus dispensing with the semantic obstacles posed by the use of national or even provincial designations, direct cross-Strait flights and cargo shipments at last will be authorised. Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, too, will soon follow Fujian’s example and incorporate their airports into existing free trade zones, thereby facilitating direct links to Taipei and Kaohsiung.

On the environment:

In some respects, the country will be more polluted than ever in 2036. For example, it is almost impossible to envision a substantial improvement in air quality without some unforeseen technological leap. Even if China’s economic base shifts from energy-intensive industries like cement and smelting towards less polluting services sectors, or even if the government manages to make China as energy efficient as Japan, it will require a lot more energy. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s current forecast is that China’s GDP will be well over three-times as large (in real terms) in 2036 as it is this year. The power needed to fuel this expansion will undoubtedly come mostly from coal. The country is thus likely to see a steady deterioration of air quality and a steady rise in acid rain and greenhouse gas emissions. Surging levels of car ownership will also see urban air pollution rise to choking levels.

On education:

With 25% of Chinese workers university-educated by 2036, generating suitable employment for the 200m-strong elite force (compared with just 20m in 2005) will become a major headache for the Chinese government. It will rely heavily on the private sector to provide employment. But even the avalanche of new job opportunities in urban areas created by the “Great Migration” of two-thirds of the Chinese population (estimated at 1.5bn in 2036) into cities will not be enough to meet the needs of the country’s well-educated workers. Increasingly, they will look for employment overseas.

On the global effect of China's economic interests:

With China’s economy continuing to rocket ahead, the country is certain to become a major source of investment for other countries 30 years from now. But will this be a good thing for the rest of the world?

In Sudan, the main reason why the UN has been so slow to introduce sanctions against the country for the atrocities taking place in the country’s Darfur region is opposition by China, a veto-wielding member of the UN Security Council. Similarly, China, along with Russia, is shielding Iran from a US-led effort to punish the oil-rich country for pursuing a suspected nuclear-weapons programme. Meanwhile, in Angola, which is now China’s largest supplier of oil, there are concerns that Beijing’s few-strings-attached investment in infrastructure is undoing the IMF’s and World Bank’s efforts to improve governance in the country.

The full text is available below for your perusal, unless you're a copyright lawyer.

Special 30th Anniversary Edition

China in 2036

20 November 2006

Economist Intelligence Unit - Business China

(C) 2006 The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd.

Anniversary issues are usually backwards-looking and self-congratulatory affairs. Most readers roll their eyes and yawn. So, in this special edition, we decided to ask our China experts to gaze into their crystal balls and offer their best guesses about what China will be like 30 years from now. Will China dethrone the US, at least economically, or will the People’s Republic break up? Will rampant pollution kill millions of Chinese in their prime, or will they be the happiest bunch of yuppies the world has known? Some of our answers may surprise you. Please read on.

Click on the links below to browse by topic:

Foreign Policy

Politics

Environment

Education

Outward Investment

Foreign policy: An unfinished quest for inner peace

China’s “soft power” in the international arena will grow, but its hard power will grow faster

Chinese leaders have always been acutely aware that weak countries have little diplomatic clout. That is, economically and militarily feeble countries—such as yesterday’s China—are at the mercy of great powers. But in light of the dazzling reversal in its economic fortunes, the notion that China’s global influence will also quickly grow through “soft power”—a term coined by Joseph Nye of Harvard University—is gaining currency among Chinese and foreigners alike. The concept, in a nutshell, refers to a country’s ability to influence others by the attractiveness of its ideas, system and culture rather than by sheer coercion.

Interestingly, many Chinese leaders still subscribe to the late Deng Xiaoping’s maxim that China should not seek the “limelight” and take the lead in international affairs before it gets economically much stronger. Even so, examples of China’s growing soft power are becoming more evident by the day. The most recent was the appointment of Margaret Chan, a former Hong Kong civil servant, as the new head of the World Health Organisation. She is the first Chinese national to lead a UN agency.

A country’s hard power and soft power often go hand in hand—as with the US. But hard power is not a sufficient condition for a country to project a lot of soft power (eg, the former Soviet Union). Conversely, a country without massive hard power can wield significant soft power. The UK, for example, punches far above its weight despite its middling economy. Why? As the world’s language of business, English, for one, gives its native speakers disproportionate clout in international settings. Meanwhile, London’s strategic location between continental Europe and the US and its pulsating cosmopolitanism have enabled it to preserve—and enhance—its traditionally pivotal role in global finance.

Spillover effect

Will China be another UK or Soviet Union? The conventional wisdom is that as China continues its swift climb up the global wealth league, its economic influence is bound to spill over into other spheres. If so, that China will wield more soft power in the long run should not be in doubt—its economy is already the world’s fourth largest and holds record foreign-exchange reserves of over US$1trn. By 2036 China’s soft power is certain to manifest itself in, among other things, more Chinese nationals at the helm of the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, IMF and the alike; a large contingent of Chinese troops in UN peacekeeping missions; and a mushrooming number of overseas Chinese language and cultural centres such as the Confucius Institutes. But less certain is the future balance between the magnitudes of China’s soft and hard power, as well as which it will choose to make greater use of.

The conventional wisdom also suggests that by 2036 the Chinese economy will have overtaken the US economy. On the assumption that China’s annual per-capita GDP growth will average 7% and that the renminbi will appreciate by 25%, Citigroup forecasts that by 2030 China will command the world’s largest economy with per-capita income of US$13,000. This seems more than plausible. China’s GDP has expanded at a double-digit clip annually for the past two decades, while the renminbi faces immense upwards pressure. History has also proven that developing countries can leapfrog developed countries if they leverage their competitive advantages and pursue sound economic policies. With its massive pool of labour, exceedingly high savings rate and close integration with the global economy, China looks very likely to become the next to do so.

That said, it is dangerous to extrapolate long-term economic growth scenarios purely based on past trends. A couple of years before the Asian financial crisis someone predicted that Thailand would catch up to France within 20 years. Today the French simply shrug and say, “imbécile!” For all that is going right for China, it faces serious challenges to continuous growth, such as an ageing population, gaping income disparity and worsening environmental degradation.

It would be equally naïve to assume that Chinese leaders will continue to adhere to Deng’s creed of self-restraint in international affairs—especially as their confidence grows in tandem with China’s might. One reason that the UK is so good at exerting soft power is because it is keenly aware of its limits and avoids hubristic overreach. The opposite is true of the US, which has recently undermined its soft power by relying too much on its awesome hard power. Alas, China will increasingly be tempted to behave more like the US than the UK.

Consider China’s relations with its neighbours. While it is true that Beijing has put its territorial disputes with Russia, Mongolia, India, Vietnam, the Philippines and Japan on the back burner, it does not mean that current Chinese leaders have forgotten about the concessions their imperial predecessors were forced to make under the “unequal treaties” imposed by stronger powers. In particular, China’s troubled relationship with Japan is almost certainly headed for some sort of “settling of the score”. China’s deep distrust of and enmity with Japan stemming from the military conflicts of the 20th century have been compounded by Beijing’s suspicion that Tokyo has been abetting the independence movement in Taiwan, a former Japanese colony. More generally, given its insatiable demand for raw materials and natural resources to fuel its industrialisation, it is safe to assume that China will become more assertive in its backyard. That is why Beijing quietly dropped the use of the phrase “peaceful rise”. The reality is that rising big powers always bully small neighbours!

China’s exercise of its far greater soft power in the future will be limited by a numbers of factors. The relatively difficult-to-fathom Chinese language is one. The gap between how a lot of foreigners see China (nervously) and how most Chinese see it (respectfully) is another. And China’s economic development, as impressive as it has been so far, is more likely than not to encounter a severe setback or two in the next 30 years. Above all, true soft power derives from a country’s inner strengths and ideals. But China still bears too many scars from its recent political history, which have eroded many traditional Chinese values and which have yet to heal completely. To truly revitalise the best Confucian principles and undo Maoism will take several generations, not a mere 30 years.

Politics: The Federal People’s Republic of China

By 2036 the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on a unitary state will only be a façade

In the coming 30 years China will split along geographic lines into a far looser political system than is currently the case. And the country’s superficial administrative coherence will, in reality, mask a number of fractures.

Following the accession of “sixth generation” politburo members in 2011, technocrats will overwhelmingly make up the senior leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They will place more emphasis on “inner-party democracy,” which, in their own minds, will entail building up systems and institutions for a more rational and efficient administration. They will not tolerate other power centres, but will allow considerable leeway in the use of alternative administrative models under CCP control. This is why successive party leaders will trumpet vaguely defined “harmonious goals” and a consensual leadership style. But much like Japan’s dominant Liberal Democratic Party, this means sharp factionalism will be the name of the game in private.

Contradictory agendas

Behind the polished façade will lie a contradiction: the “central” government will be increasingly restrained by forces of decentralisation. Since the beginning of the market-opening era in the early 1980s, the leadership in Beijing has relied on consensus among provincial leaders concerning the pace of reforms and burden-sharing for the social costs imposed by economic change. But efforts at tax-sharing agreements and transfer payments will degenerate into a series of debilitating political struggles for Beijing. This will inexorably alter the balance of power in favour of provincial bodies. Such changes, though, will be incremental and the result of crafting specific political bargains. These exercises will, in turn, be both reinforced and exacerbated by factionalism. Favouritism within the politburo will exploit regional loyalties, university alumni networks and the increasingly intertwined linkages among the corporate and political elites.

There will be nothing like a constitutional conference to debate the political framework of this new China. In truth, however, the tradition of ad hoc arrangements will be convenient for not only the provinces, but also the Special Administrative Regions (SARs) of Hong Kong and Macau, as well as the de facto SAR of Taiwan. Throughout the reform period, there have been several precedents for the decentralisation of political power: China’s five Special Economic Zones (SEZs) have been given legislative authority akin to provinces in the early 1990s, and have successfully “piloted” legislation for a number of corporate-sector reforms.

In a more imaginative application of creative ambiguity, the province of Fujian will pioneer the use of “free trade investment zones” with their boundaries extending to include airports and ports in both Fuzhou and Xiamen. By thus dispensing with the semantic obstacles posed by the use of national or even provincial designations, direct cross-Strait flights and cargo shipments at last will be authorised. Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, too, will soon follow Fujian’s example and incorporate their airports into existing free trade zones, thereby facilitating direct links to Taipei and Kaohsiung.

The flip side of such economic decentralisation will entail the off-loading of social obligations, such as education and healthcare, to sub-provincial levels of government. Despite the “harmonious society” policies initiated by Hu Jintao—the Chinese president from 2002 to 2012—and the subsequent attempts to consolidate and standardise provision of public goods, their delivery will remain mostly in provincial hands. The central government will have some success unifying funding options, but its traditional tolerance for discrepancies in standards of governance among localities will only grow.

Regions, naturally, will champion different issues. For example, some will emphasise greater environmental protection. Others, such as Xinjiang and Tibet, will stress mother-tongue instruction in the school system. These differences will become particularly apparent at sessions of the National People’s Congress, during which provincial caucuses will engage in spirited lobbying of central ministries.

In 2036, as in 2006, the Chinese government’s mantra will be preservation of the status quo. But it will not be able to preserve the status quo at all. In fact, incremental tinkering in the centre-periphery relationship will make the balance of power even more lopsided and differences in governance at the provincial level even more pronounced. Formalisation of a new centre-periphery power-sharing arrangement will be discussed with more frequency and urgency within Zhongnanhai. But no consensus with China’s 31 provinces and regions will be reached.

Numerous think-tank conferences on the topic of federalism will get bogged down on the knotty issues of the treatment of the SARs—and the precedent that would be set by absorbing them into the Chinese political system while at the same time according them special status. Hong Kong’s “high degree of autonomy” is due to expire in 2047, and the politburo will be keen to transform Hong Kong’s de facto economic convergence with the Shenzhen SEZ into a de jure accord. Similarly, Taiwan’s effective surrender of full sovereign claims—through its participation in free-trade zones and preferential customs arrangements with the mainland—will need to be normalised in a comprehensive agreement according the island “autonomous” status within China.

Re-defining Beijing’s asymmetrical balance of power with its various dependent jurisdictions will require political maturity to conceptualise possible solutions and political will to implement them. Whether Beijing and the provinces are up to this task will be of decisive consequence to China’s political evolution through 2036—and well beyond that.

Environment: Saying “no” to growing filthy rich

China will be a (relatively) cleaner place 30 years from now

China’s economic rise represents one of the most potent challenges to the environment that the world has ever faced. Environmentalists fret, for example, that if a more developed China produced urban waste at the same rate as the US does today, there would be 3bn tonnes of the stuff every day. This prompts many to call on China to find a “new paradigm for development”, lest its quest for a better-off society ends up trashing a big chunk of the planet. But comparisons with developed countries in 2006 and extrapolations of existing trends probably present a very distorted picture of China’s environment in 2036. In many ways, China will be a cleaner place by then.

Changing priorities

The fundamental problem with extrapolating current trends into tomorrow, is that China’s government has only recently begun to pay attention to environmental issues. In the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-10), the government has emphasised, for the first time, the need to strive for quality as well as quantity in output. Environmental goals, such as more efficient power and water usage, have been instituted. A renewable energy law came into effect at the start of 2006, mandating power generators to buy from renewable-energy producers. The State Environmental Protection Agency, only raised to ministerial rank in 1998, has also gradually been given more teeth and muscle.

One can take a cynical view of how effective all this will be—in the short term. Energy consumption outpaced GDP growth in the first half of 2006, making a mockery of the target of reducing the amount consumed per unit of GDP by 4% this year. But in the long term, growing pressure from local and international sources will keep the focus on environmental matters, and this will inevitably lead to some change for the better. Already, incremental but significant steps are being made, such as the government’s levy on electricity sales, which goes towards supporting the development of renewable energy.

The most obvious improvements will come in two areas: water and desertification. Arguably China’s water supplies could not get any worse than they currently are—around 90% of urban underground water is polluted, as are 70% of China’s rivers and lakes. Partly because the situation is already so dire, water pollution will be a priority for the government and, happily, progress in the next 30 years will be relatively easy. Treatment of urban sewage will rise rapidly from the current level of 52%. And tougher enforcement of environmental regulations will persuade a growing number of firms to invest more in waste-water treatment systems. While China’s pungent waterways in 2036 will not be at risk of attracting hordes of recreational swimmers, the majority will be substantially cleaner.

The scourge of spreading deserts will also likely pose less concern in 2036 than it does today. The pressure on China’s rural areas will ease as more Chinese migrate to the cities, turning the country from a rural-majority to an urban-majority one. Some might argue that the benefits of fewer farmers could be offset by more intense usage of the land. But this trend, in turn, will be offset by the simultaneous retreat of government support for farming in the most marginal agricultural terrains, which will encourage farmers to concentrate in more fertile regions. This process is already underway—by the end of 2005 around 23m ha of infertile farmland had been returned to woodland or grassland.

China’s environmental future is not all gleaming, however. In some respects, the country will be more polluted than ever in 2036. For example, it is almost impossible to envision a substantial improvement in air quality without some unforeseen technological leap. Even if China’s economic base shifts from energy-intensive industries like cement and smelting towards less polluting services sectors, or even if the government manages to make China as energy efficient as Japan, it will require a lot more energy. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s current forecast is that China’s GDP will be well over three-times as large (in real terms) in 2036 as it is this year. The power needed to fuel this expansion will undoubtedly come mostly from coal. The country is thus likely to see a steady deterioration of air quality and a steady rise in acid rain and greenhouse gas emissions. Surging levels of car ownership will also see urban air pollution rise to choking levels.

The most important challenge for China will be enforcing its environmental regulations. Progress will depend on establishing an independent judicial process and actively engaging China’s civil society. Fortunately for China and for the outside world, the indications to date suggest that the environment will be at the vanguard of reforms pushing the country towards both these goals.

Education: More is better

China will produce millions of new university graduates who will be generally smarter, wealthier and happier

Disparities are entrenched (or embraced?) as a way of life in China. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the classroom. Even 30 years from now, at rural schools, the chalk and blackboard will remain the primary teaching prop. At city schools, though, the palmtop computer will be taken for granted. The iron-rice-bowl egalitarianism of the pre-1979 era will only get a brief mention in a course on history—not a popular subject, incidentally, for China’s über-achievers obsessed with a more brilliant future.

As China’s economy grows bigger and races up the value chain, will its educational system be able to supply the armies of qualified workers the country needs? The short answer is yes—with a lot of help from the private sector. Many more Chinese university students will be trained at tertiary institutes set up by private business and home-grown philanthropists. By the end of the 16th Five-Year Plan (FYP—2031-35) Chinese universities will be producing about 8m graduates each year, or about 1% of the workforce.

With government expenditure on education peaking at 4% of GDP under the 11th FYP (2006-10), the private sector will shoulder the extra spending demand. These private institutions of higher learning will be more in tune with economic demands than the traditional state-run universities. This will result in twice as many privately funded universities with full undergraduate courses as state-run ones, compared with the 1:20 ratio in 2006.

Following in the footsteps of Beijing Geely University, every leading enterprise (numbering about 100) in the country will operate an institution of higher education. They will generally offer a curriculum patterned after Ivy League schools in the US. These enterprise universities focused on teaching directly relevant skills required by the job market will be more sought-after than many joint-venture campuses set up by China’s traditional academic institutions and their Western counterparts.

Always flexible, the country’s erstwhile party schools—funded by a club of 100m-strong well-heeled “communists” who were the first to be allowed to get rich—will aim to offer the world’s best MBA facilities at well-manicured campuses equipped with five-star restaurants and hotels for teaching staff and students from all over the world. These schools will also operate the highly popular Confucius Institutes, first set up in 2004 in South Korea, to promote Chinese language and culture to foreigners. Students will be drilled in the core Confucian philosophy of social harmony, collective responsibility and, most importantly, respect for authority. Foreign governments besieged by religious terrorism and ethnic unrest will find it especially useful to send their bureaucrats to China for such an education.

No thanks to humanities

The privatisation trend will reinforce the country’s bias in favour of science and engineering, as product innovators and infrastructure builders continue to attract great market demand. China will remain the single largest supplier of engineers in the world with some 4m graduating in the discipline each year, compared with a paltry 120,000 in the US. But the US will still lead in technological innovation, as the country’s liberal environment continues to inspire a gaggle of geeks in both the classroom and the garage.

With 25% of Chinese workers university-educated by 2036, generating suitable employment for the 200m-strong elite force (compared with just 20m in 2005) will become a major headache for the Chinese government. It will rely heavily on the private sector to provide employment. But even the avalanche of new job opportunities in urban areas created by the “Great Migration” of two-thirds of the Chinese population (estimated at 1.5bn in 2036) into cities will not be enough to meet the needs of the country’s well-educated workers. Increasingly, they will look for employment overseas.

With considerably fewer peasants left after the great urban migration, farms will become relatively larger and farming more mechanised. Agricultural institutes, financed by private investors who see an opportunity to capitalise on a “green revolution”, will fan across the country, teaching farm management and new cultivation methods.

Despite the persistent rural-urban divide, farmers’ income levels will increase with higher-value crops and economies of scale. Mob violence will flare up on occasion, but these will be driven less by wealth disparities than by local injustices. Such actions will lack national appeal. A better-educated population, preoccupied with self-advancement, will have little interest in rocking the system.

Outward investment: Tainted money

Rising overseas investment by Chinese companies will help keep despots around the world in business longer

One less-noted feature of China’s current economic boom is the strong growth in outward foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2005 Chinese investment abroad surged by 526% compared with 2004, reaching US$11bn. With China’s economy continuing to rocket ahead, the country is certain to become a major source of investment for other countries 30 years from now. But will this be a good thing for the rest of the world?

The experience so far, especially in Africa where China has been on an investment spree, suggests that the longer-term impact will be far from positive. Indeed, China is coming under criticism from various international observers for undermining Western attempts to improve governance and reduce corruption in African countries. China, for instance, is blamed for abetting genocide and human rights abuses in Sudan. To maintain access to the country’s oil, China has refused to censure the internationally ostracised regime in Khartoum. If these are early signs of China’s future behaviour abroad, the outside world would be right to worry.

The main factor driving China’s outward FDI is its need to secure the energy resources and raw materials, such as copper and iron ore, that are necessary to fuel the country’s booming economy. With domestic production of oil stagnant, and demand forecast to grow by around 7% a year, China in particular is becoming a central player on the world energy scene. This is why, despite the unsuccessful attempt by the state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corp in 2005 to take over Unocal, a US-based oil firm, Chinese energy companies will continue to look abroad.

China’s hunger for oil and other natural resources means much of China’s future investment will flow to developing countries in Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East. However, even as China gets richer and more powerful, Western observers fear that it may continue to pursue only its narrow self-interests rather than doing its part to help solve global problems.

In Sudan, the main reason why the UN has been so slow to introduce sanctions against the country for the atrocities taking place in the country’s Darfur region is opposition by China, a veto-wielding member of the UN Security Council. Similarly, China, along with Russia, is shielding Iran from a US-led effort to punish the oil-rich country for pursuing a suspected nuclear-weapons programme. Meanwhile, in Angola, which is now China’s largest supplier of oil, there are concerns that Beijing’s few-strings-attached investment in infrastructure is undoing the IMF’s and World Bank’s efforts to improve governance in the country.

Of course, China may amend its ways as time goes by. Part of the reason why Chinese companies so often act “unethically” is due to their lack of international business experience. And the root of Chinese firms’ bad behaviour lies in weak domestic corporate-governance standards and managerial transparency. As standards at home improve, the behaviour of Chinese companies abroad should also improve.

Few good choices

Less certain is whether the behaviour of the Chinese government will change. On the one hand, “non-interference” in the affairs of other countries is enshrined in China’s foreign-policy doctrine. On the other hand, China does not deliberately set out to make allies of the world’s pariah regimes. It is just that, as a late entrant in the race to secure access to raw materials, China is often left with little choice but to invest in countries like Sudan, which have been abandoned by many Western countries.

China is increasingly keen to be seen as a responsible global power. If so, the Chinese government must start acting the part. As long as it continues to turn a blind eye on genocide and cosy up to despots like Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, the rest of the world will wonder if China’s overseas investment will truly benefit recipient countries in the long term.

END ITEM

posted November 21, 2006 at 10:43 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (30)

November 15, 2006

Fragrant Pears in the NY Times

The New York Times' Dining & Wine section features an article on Korla's fragrant pears today. As the photos I published on this website in September are among the only ones available online showing the pear harvest, the Times asked me for permission to use one along with the story. I suppose I should have found out if my friend, Mohammed, minded having his picture in America's newspaper of record before granting their request. Oh well, too late now... but doesn't everyone want their picture in the NY Times?

From the article:

The pears, as crisp as Asian pears but juicy and sweet like more familiar varieties, originated in far western China in the Xinjiang region. The area accounts for only 3 percent of China’s pear crop, but the Fragrant variety, which its farmers have cultivated for 1,300 years, is esteemed as the country’s finest, and fetches twice the price of other pears there.

Fragrant pears are fairly small and roughly oval, with long stems. The light green or yellow skin, with a reddish blush on some fruits, is thin and readily edible; the flesh is extraordinarily tender, crisp and juicy. The flavor is delicate, and different from that of most Asian pears, with a whiff of the “pear ester,” ethyl decadienoate, which gives European varieties their characteristic aroma. Ready to eat after harvest in September, they can keep in commercial storage for up to a year.

So, congratulations to me for getting my first photograph in the NY Times. (No, they didn't pay me. And yes, a photograph containing my likeness has been in that paper before, but it wasn't shot by me.) As always, you can read the full article below, or here.

From Silk Road to Supermarket, China’s Fragrant Pears

The New York Times

November 15, 2006

By DAVID KARP

JADE-GREEN Fragrant pears, with exotic provenance and a legendary reputation, have arrived in the United States for the first time after a journey that evokes Marco Polo.

The pears, as crisp as Asian pears but juicy and sweet like more familiar varieties, originated in far western China in the Xinjiang region. The area accounts for only 3 percent of China’s pear crop, but the Fragrant variety, which its farmers have cultivated for 1,300 years, is esteemed as the country’s finest, and fetches twice the price of other pears there.

The Fragrant pears, which have been exported to the United States since last month, are grown around Korla, a stop on the ancient Silk Road that is now an oil boomtown with more than 420,000 residents. West of the Gobi Desert and north of the Taklimakan Desert, Korla draws water from the Konqi or Peacock River, which flows south from the Tian Shan Mountains.

In recent decades Chinese government policy and market reforms have encouraged farmers to sharply increase pear production, which is expected to reach 12.5 million metric tons this year, more than two-thirds of the world’s supply. Virtually all are Asian pears, crunchy and ripe off the tree, not the European kind, such as Bartlett and Bosc, which develop their desired buttery texture and rich flavor after harvest.

Fragrant pears are fairly small and roughly oval, with long stems. The light green or yellow skin, with a reddish blush on some fruits, is thin and readily edible; the flesh is extraordinarily tender, crisp and juicy. The flavor is delicate, and different from that of most Asian pears, with a whiff of the “pear ester,” ethyl decadienoate, which gives European varieties their characteristic aroma. Ready to eat after harvest in September, they can keep in commercial storage for up to a year.

Xinjiang lies at the intersection of the ranges of Asian pears — which are mostly grown in China, Korea and Japan — and European pears, which evolved later in the Caucasus Mountains and Asia Minor. The botanical identity of Fragrant pears has long been unclear, and Chinese trade documents describe them as resembling the European species. In a study published in 2001, however, scientists analyzed the variety’s molecular markers and determined that it is a complex hybrid of the two main European and Asian species, along with Pyrus armeniacifolia, a little-known Xinjiang species with small fruits and leaves similar to apricot foliage.

Xinjiang’s political situation is unsettled, as an influx of Han, China’s main ethnic group, has fed separatist agitation and terrorism by the mostly Muslim Uighurs, who are now a minority in their homeland. Korla has long been renowned for its fruit — melons and grapes, as well as pears — and the Chinese government has sought to relieve economic pressures by promoting exports.

Chinese officials asked to export Fragrant pears to the United States in 1993, but American pear growers raised concerns that the imported fruit might introduce exotic plant pests and diseases. Only after repeated visits by Department of Agriculture scientists, pest risk assessments and revisions of inspection procedures did the department grant approval last December.

The only other Chinese pear allowed in the United States is the Yali (Ya) pear, or duck pear, a major commercial variety that is durable but mediocre, with tough flesh and bland flavor.

Jacky Chan, managing partner of YW International, a fruit importer, traveled to Korla twice this year to arrange for shipments of Fragrant pears.

“If I didn’t go, they wouldn’t have sent us the best quality,” he said in an interview in his office in South El Monte, Calif., east of Los Angeles.

The lengthy journey taken by Fragrant pears may not endear them to environmentally conscious shoppers concerned with food miles. Mr. Chan, 29, said that workers at the packing house in Korla use air guns to clean the pears of insects and debris, check them with magnifying glasses, and then cushion them in tissue paper and foam mesh sleeves for the journey ahead: seven days by truck, over small roads as well as highways, to Shenzhen, a port near Hong Kong; two weeks by container ship to Long Beach, Calif.; and another five days by truck to New York.

Several other importers are bringing in the pears, which are available at grocery chains including Hong Kong Supermarkets in New York, 99 Ranch Markets in California and H-E-B stores in Texas; they are also expected to show up soon at fancy New York markets such as Agata & Valentina and Dean & DeLuca.

Knowing that Fragrant pears would soon arrive from China, John M. Wells, co-owner of Viewmont Orchards, in Hood River, Ore., visited China in 2004 and brought back cuttings of the variety, which he intends to propagate and plant next spring.

“I’m trying to figure out whether the tree will grow here,” he said.

posted November 15, 2006 at 03:20 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (51)

Return of the Sexy Uzbeks!

Despite the fact that they turned out be Uzbek, I stick by my original assertion six months ago that Shahrizoda's music is Uyghur pop. Uzbeks and Uyghurs are about as close as two ethnicities can get, and it seems to me that the group's popularity here in Xinjiang at least makes them honorary Uyghurs.

The entries on this site containing the videos for Shahrizoda's two super-hits (found here and here) have turned out to be the most popular posts in this blog's short history. The songs are now Xinjiang classics, which I've since heard playing in locales as distant as Beijing and Lhasa. A few samples of the, ermmm... praise they've received in the comments section:

Hi

i m frm pakistan.i really enjoy this music,and now i m a great frnd of this band.i like this band .i love the girl in black dress and i want her e-mail address.plz mail me the e-mail address of all girl in this band.

thank u

Ramiz

Hi Dearest and Sweetest heart throb, I like all of them three very much but the reason is that i don't know their names. After all i would like to say that about them. they are dead beutiful. i have no words to say about their great job. If i got a chance God Willing i'll meet them. They are the best...

Farooq Khan

Hi

Salam to u all girL.

I like u all very much .

U all very atractive.

Email me u all .

I am waiting for ur email.

I like ur dance and program.

Asif Khan

Writing something here is just like wasting of time. just write one massege to any singer of Pakistan. U'll get response. I wrote many massege here but in vain. So beware from writing here... Because These singers are vey heity-tiety.....

Farooq Khan

And so on and so forth. People seem to think that just because I post the videos, I must be chillin' with Shahrizoda every weekend here in Korla. If only it were true! The girls are so popular in Xinjiang these days that a photo of the "hot one" has even been spotted on a box of Uyghur hair dye:

Anyway, the point of this entry is to post one last Shahrizoda video for all the freaks and addicts out there. (I don't mean drugs - I'm talking about Uzbek-Uyghur pop addicts.) You can watch the videos for a number of their other songs if you search YouTube, but this one wasn't among those available until today.

It's a little pop number with a heavy Russian feel, including a catchy disco-accordion melody. Not as infectiously awesome as their two most famous songs, but worth a look (if only for the hip-shaking). Like many of Shahrizoda's more basic videos, it appears that this club performance was shot at Mix Bar (on Renmin Gongyuan Beijie) in Urumqi:

Please direct your Shahrizoda-related unreasonable requests towards the comment section below.

posted November 15, 2006 at 12:10 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (42)

November 13, 2006

Xinjiang's AIDS Problem: Heroin.

There's a good article in the NY Times today about Xinjiang's AIDS problem. We've got the highest infection rate in China here, officially standing at about 0.3% of the population... although it may be as high as 1.2%. The spread of AIDS seems to be more of a drug problem than a sex problem, though, with most of the local heroin addicts apparently unaware that sharing needles is a bad thing. Luckily, attitudes to drug treatment and education are changing in China:

With a population of about 20 million and an officially estimated 60,000 infections, Xinjiang has one-tenth of China’s AIDS cases and the highest H.I.V. infection rate in the country. Chinese authorities estimate that Kashgar Prefecture, with a population of about three million, has 780 cases, but public health experts here say the real figure is probably four times that and rising fast.

Until recently, addicts were largely left to the police, who regarded them as simple criminals whose drug use was to be combated mercilessly. Resistance to treating drug addiction as a public health concern has been high, mirroring what some international health experts say was a slow response to the virus generally in China as AIDS first gained a foothold.

“Some cadres are not willing to launch a public campaign against AIDS, fearing it would affect their image and investment in their locality,” said Parhat Halik, the deputy commissioner for Kashgar Prefecture, in a speech in June. “Some are still having endless debates about whether to promote the use of condoms, methadone treatment and needle exchange programs, or standing in the way of initiatives to work with high-risk groups. That is our biggest problem in the fight against AIDS.”

You can read the full article below.

China’s Muslims Awake to Nexus of Needles and AIDS

November 12, 2006

The New York Times

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

KASHGAR, China, Nov. 6 — The story of Almijan, a gaunt 31-year-old former silk trader with nervous eyes, has all the markings of a public health nightmare.

A longtime heroin addiction caused him to burn through $60,000 in life savings. Today, he says, all of his drug friends have AIDS and yet continue to share needles and to have sex with a range of women — with their wives, with prostitutes, or as he said, “with whoever.”

For now, Mr. Almijan, whose name like many here is a single word, seems to have escaped the nightmare. His father carted him off to a drug treatment center hundreds of miles away in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region here in China’s far west.

When he relapsed, he was arrested during a drug deal. That landed him in a new methadone clinic, opened last year in this city, where he spent three months cleaning himself up. He says he has repeatedly tested negative for H.I.V.

This day, fresh from a clinic just off of People’s Square here, watched over by a huge statue of Mao, Mr. Almijan slurred thickly after drinking the dose that keeps his cravings at bay. “If I can help other people, I’d be happy to tell you my story,” he said. He explained why he had embraced treatment: “My friends were dying, and I was very afraid.”

The way the authorities handled Mr. Almijan, including his treatment with methadone, is part of a sea change by the Chinese public health establishment, which is struggling to confront an increase in intravenous drug use and an attendant rise in AIDS cases in Xinjiang, an overwhelmingly Muslim region close to the rich poppy fields of Afghanistan and near the border with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

With a population of about 20 million and an officially estimated 60,000 infections, Xinjiang has one-tenth of China’s AIDS cases and the highest H.I.V. infection rate in the country. Chinese authorities estimate that Kashgar Prefecture, with a population of about three million, has 780 cases, but public health experts here say the real figure is probably four times that and rising fast.

Until recently, addicts were largely left to the police, who regarded them as simple criminals whose drug use was to be combated mercilessly. Resistance to treating drug addiction as a public health concern has been high, mirroring what some international health experts say was a slow response to the virus generally in China as AIDS first gained a foothold.

“Some cadres are not willing to launch a public campaign against AIDS, fearing it would affect their image and investment in their locality,” said Parhat Halik, the deputy commissioner for Kashgar Prefecture, in a speech in June. “Some are still having endless debates about whether to promote the use of condoms, methadone treatment and needle exchange programs, or standing in the way of initiatives to work with high-risk groups. That is our biggest problem in the fight against AIDS.”

But since 2005, the authorities in Xinjiang have been trying everything from needle exchanges and drug substitution programs — approaches that first became popular in the West in the 1960s — to community outreach programs, often giving briefings to imams and mullahs.

The people of Xinjiang are ethnically distinct from China’s Han majority, and have a long history of distrust of the central government.

In the narrow, winding alleys of this city, where most women wear veils and mosques can be found every hundred yards or so, Islamic clerics spoke enthusiastically about antinarcotics efforts.

“These people are killed and arrested, persecuted and punished by the police, and the price of their drugs becomes greater even than gold, and yet they continue to use them,” said Abdu Kayaum, imam at a small brick mosque here. “If I didn’t preach about these ills, I wouldn’t be a Muslim.”

At another mosque, the muezzin, or prayer caller, Abulkasim Hajim, put it slightly differently, saying: “This is not just a problem for the government, it’s a problem for our people. The people who use drugs are going to die, but before they do so, they will waste their family’s money and cause a lot of suffering.”

Mr. Hajim might well have been speaking of Mr. Almijan, whose costly 12-year habit ruined his family’s lucrative silk trading business, left him deep in debt and finally reduced him to a lowly job at a small hotel.

Now, less than a month out of detention in the treatment center, he reports most days to the clinic near Yuandong Hospital where he goes voluntarily to drink a dose of methadone under the watchful eye of a video monitor. Each treatment costs him about $1.20.

“All my money has gone up in smoke,” Mr. Almijan said, explaining that he lacks the capital to get back into the silk trade. “My friends all shared needles when I was using drugs. At least I understood how bad that was and only used my own.”

Another heroin addict, a fruit seller dressed in a tweed jacket who goes by the name Ablimit, said he started injecting heroin in 1999. “I had a bunch of friends invite me to try heroin,” he said. “They either shared a lot of needles or they overdosed. They’re all dead now.”

Mr. Ablimit, who said he had tested negative for H.I.V., has tried to break his heroin addiction many times, including a previous bout with methadone. He recently spent 45 days in a methadone treatment center after his wife caught him shooting up at home and threatened to leave him.

He said that while methadone had given him great relief from cravings for the drug, it was a not a cure. Cravings return when the methadone wears off, and weaning recovering heroin addicts from the replacement drug can be as hard as quitting heroin itself — and some say harder.

Nowadays, Mr. Ablimit works in a neighborhood recreation center, where he helps counsel other addicts and reports less and less frequently to a methadone clinic for a dose of the drug he is trying to wean himself from.

“You can take methadone as long as you want,” he continued, his wife looking on. “But I’ve got children and want to be a regular person. I want to atone for all the bad I have done.”

posted November 13, 2006 at 12:41 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (53)

November 12, 2006

Xinjiang News for 2006.11.11

Two interesting news items for you today...

Xinhua: Crazy Monkey Taunts Xinjiang Motorists

The macaque ran onto the highway linking Turpan and Urumqi cities at about 4:00 p.m. on Thursday and traded his mountain life for an exciting experience amid the traffic flow, witnesses said.

The creature found a safe spot on the partition belts between the highway lanes, waving his "hands" to "greet" drivers who passed him.

What's more, he jumped off and started racing with the swiftly-passing vehicles, overjoyed but unaware of the dangers and troubles it made to the traffic. (link)

IPS: Korla's Oil Riches vs. the Taklamakan Desert

With its karaoke bars, oversized department stores and a neon-lit promenade along the man-made Peacock River, the city strives to be a mini-replica of booming metropolises of the east coast like Shanghai.

Yet there is one flaw that has escaped local officials' drive for perfection. Being only 70 km from the desert, the city is plagued by fierce desert storms that ravage the fragile vegetation and blanket the skies for days in the spring.

It rains so little that the locals remember every day of the year when it happened. The drought sucks all the moisture from the soil, making it an easy prey for the storms. Encircled by dry mountains from all sides, Korla gets whipped by sand that is picked up by the wind and deposited on every visible surface. It happens some 40 days every year.

So desperate were local officials to tame the storms that in mid-1990s they embarked on a scheme to level off some of the surrounding hills by blowing them up. (link)

You can read the full articles below.

Naughty monkey teases traffic police on highway

Naughty monkey teases traffic police on highway

11 November 2006

Xinhua News Agency

URUMQI, Nov. 11 (Xinhua) -- A mischievous macaque believed to have escaped from a zoo barged into a highway and gave five traffic police officers a hard time catching him in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

The macaque ran onto the highway linking Turpan and Urumqi cities at about 4:00 p.m. on Thursday and traded his mountain life for an exciting experience amid the traffic flow, witnesses said.

The creature found a safe spot on the partition belts between the highway lanes, waving his "hands" to "greet" drivers who passed him.

What's more, he jumped off and started racing with the swiftly-passing vehicles, overjoyed but unaware of the dangers and troubles it made to the traffic.

Witnesses called the local traffic police and five police officers spent about 20 minutes trying to capture the dodging animal, but their efforts failed.

A police officer held out a bottle of green tea drinking water to seduce the macaque, and he rose to the bait but was seized from behind when trying to grab the bottle.

Yet the macaque managed to break away from the human hands and escaped again.

The naughty creature was finally caught by workers with the Xinjiang Tianshan Mountain Safari Park where it had fled, a spokesman with the park told Xinhua on Friday.

CHINA: A CITY BUILT ON MAO'S ORDER FIGHTS AN ENCROACHING DESERT

By Antoaneta Bezlova

8 November 2006

Inter Press Service

BEIJING, Nov. 8, 2006 (IPS/GIN) -- When the city of Korla rose from the Taklamakan desert in mid-1950s, it was marvelled as a triumph of human willpower over adverse nature.

Thousands of soldiers dispatched by the Chinese Communist Party put this place on the map in China's far west Xinjiang, by digging 600 km of channels to coax underground water to large collective farms.

Half-a century later, Korla has to defend every bit of its existence in the desert by erecting sentries of trees against the encroaching sands. It has to fight for every drop of water by using sophisticated water conservation technology imported from Israel.

While the gleaming modern centre of today's Korla is a far cry from the cluster of shacks this place used to be in the 1950s, the enormous efforts to build and maintain it have exhausted local ecology to a degree causing people to question the wisdom of creating it in the first place.

"If it wasn't for the oil in the desert, this place wouldn't have survived," says Tian Yugang who works on the afforestation of the city.

Like many other settlers in Korla Tian comes from inland China. His parents -- members of China's paramilitary corps, or Bing Tuan, were sent to isolated Xinjiang by chairman Mao Zedong in the 1950s to open up new land and build new cities.

It was the Bing Tuans that secured the subjugation of this Muslim-populated territory for the rule of the distant communist rulers in Beijing. It was the Bign Tuans too that set into motion the backbreaking work of introducing farming in this arid land where there is insufficient water.

The economic magnet of this rugged place though is the abundance of oil extracted in the Taklamakan desert, which has kept the Han Chinese coming to Korla since the oil discovery in the late 1950s.

Korla now hosts the headquarters of Tarim Oilfield Co, a unit of the state oil giant, PetroChina, and receives throngs of visitors from foreign firms interested in the oil and gas reserves in China's western deserts.

With its karaoke bars, oversized department stores and a neon-lit promenade along the man-made Peacock River, the city strives to be a mini-replica of booming metropolises of the east coast like Shanghai.

Yet there is one flaw that has escaped local officials' drive for perfection. Being only 70 km from the desert, the city is plagued by fierce desert storms that ravage the fragile vegetation and blanket the skies for days in the spring.

It rains so little that the locals remember every day of the year when it happened. The drought sucks all the moisture from the soil, making it an easy prey for the storms. Encircled by dry mountains from all sides, Korla gets whipped by sand that is picked up by the wind and deposited on every visible surface. It happens some 40 days every year.

So desperate were local officials to tame the storms that in mid-1990s they embarked on a scheme to level off some of the surrounding hills by blowing them up.

"We thought this would decrease the sand carried by the wind and would help us irrigate the land better," recalls Zhang Yizhi, vice-director of Korla's Afforestation Bureau.

At the time Beijing had declared a nationwide battle on encroaching deserts by erecting an enormous "green wall" in the areas worst hit by desertification. Korla had its share -- some 13,000 hectares of land allocated by the central government, in a massive tree-planting scheme to hold back the deserts.

But while Korla could plant the trees it could not irrigate them properly because of its hilly terrain. Blowing up a few of the hills encircling the city didn't produce the result city leaders had hoped for. It was impossible to alter entirely the vast stretches of rocky outcrops surrounding the place.

The miraculous solution came in the shape of a dripline irrigation technology introduced by the Israeli company Eisenberg Agri Co. Ltd (EAC). It uses a pressurized system of several main pipes and hundreds of drip lines that can carry the water up the hill and deliver it through sprinklers to the roots of every tree.

"The brilliant thing about this technology is that the water pressure and volume are the same on top of the mountain and at the bottom of it," gushes Korla's vice-mayor Qu Sihao. "It really works here because all we have are hills".

While in the past it would take 800 to 1000 cubic meters of water to irrigate one mu (0.067 hectare) of land with planted trees, now the city can save 75 percent of the water. Since introducing the technology in 2001, Korla leaders claim to have successfully planted more than 3,000 hectares with trees.

The resources mobilized to achieve this are mind-boggling. The government is spending 1,167 yuan (148 US dollars) per every mu of newly planted trees along with an annual payment of 184 yuan (23 dollars) for maintaining it.

Mar. 12 has been declared a Tree Planting Day and every year local government leaders join thousands of people who take up shovels in a mass campaign to plant trees.

Zhang, at the local afforestation bureau, believes the strategy is paying off. In the past five years desert storms have decreased by 6 to 7 days and Korla's summer temperature is slightly lower. Yet the place is continuously dry and the tree belt created resembles a small green dent in an ocean of sand.

The gains are tiny compared with the environmental losses during the past five decades of water overuse and excessive farming. Overall, Xinjiang faces an uphill battle in reversing the tide of ecological degradation because its scarce water resources are mostly from glacier mountains and concentrated in two to three months in the summer. More than a quarter of Xinjiang's territory is covered in desert.

This year China claimed a victory in slowing the spread of deserts, saying the rate at which the desert is eating up farm and other land had slowed from 10,400 sq km to about 3,000 sq km a year.

Lester Brown, the president of the United States-based Earth Policy Institute, however, believes China is losing the centuries-old war against the deserts.

"A huge dust bowl is developing in western China," he says, "perhaps the world's largest conversion of productive land into desert we have witnessed so far".

(*The Asia Water Wire, coordinated by IPS Asia-Pacific, is a series of features around water and development in the region.)

posted November 12, 2006 at 12:07 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (13)

November 10, 2006

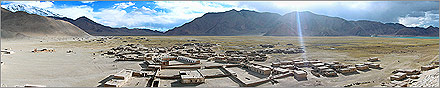

The Most Beautiful Place in Xinjiang

I've been messing around with Panorama Factory recently. The program does what it advertises and makes truly beautiful panoramas. I tend to snap panoramas here and there when I'm travelling, but have rarely pieced them together... until now.

I shot the photograph below when I traveled to Lake Karakul south of Kashgar, earlier this year. Shot from a hillside, this panorama encompases snow-capped Mustagh Ata (7500m) on the left, the ethnically Kyrgyz village of Subash in the middle, and the brilliant turqoise waters of Lake Karakul on the right. I didn't let the fact that the sun was about to set in my face ruin the picture... in fact, I think it adds to the overall effect.

Let it be proclaimed across the land, then, that Lake Karakul is the most beautiful place in Xinjiang:

Click on the image above (or here) to see the full-sized panorama at 3000×600 pixels. If your browser shrinks wide images, make sure to expand this one to full size. Stiched together, the picture is pretty awesome. (Please allow me a self-congratulatory pat on the back this one time.)

Special Bonus Image: The panorama below was taken from the other side of Lake Karakul. If you view the full-resolution version, I've marked an "×" at the hillside spot from where the first image above was taken:

UP NEXT: The ugliest place in Xinjiang.

posted November 10, 2006 at 09:54 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (16)

November 07, 2006

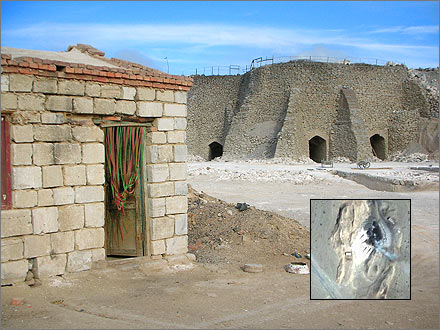

Mysterious China: Targets in the Desert

It's no secret that Korla is a city of some military importance. A few of you may remember my discovery on Google Maps last year of PLA fighter jets sitting on a runway south of Korla. With those jets flying overhead almost daily, there must be something going on around here. I was browsing the Korla area using Google Earth recently when I noticed a series of strange-looking marks in the desert east of the city. Not just any old marks... but the unmistakable "bomb-me" outline of a target with crosshairs. The roar of a jet engine overhead made everything click.

It's no secret that Korla is a city of some military importance. A few of you may remember my discovery on Google Maps last year of PLA fighter jets sitting on a runway south of Korla. With those jets flying overhead almost daily, there must be something going on around here. I was browsing the Korla area using Google Earth recently when I noticed a series of strange-looking marks in the desert east of the city. Not just any old marks... but the unmistakable "bomb-me" outline of a target with crosshairs. The roar of a jet engine overhead made everything click.

It's not that I was scanning the desert inch-by-inch for oddities... I had the Google Earth Community layer turned on and some wackos had already put placemarks there before I got the chance. It's a bit depressing to think there are people out there scanning the globe at close-range in order to find "UFO landing sites" and the like. But these markings — which appeared to be practice bombing targets of some sort — are out in the desert just a few miles east of my current location, so I knew I'd get the chance some day to take a closer look.

I've been occasionaly tutoring a student in English for the past couple of months, and when his "uncle" lent him a Jeep this past weekend I suggested an attempt at finding these strange signs in the sand. The journey started out poorly: our vehicle got stuck in the sand near Korla's new development zone and we had to be rescued by a shovel-wielding but friendly manual laborer. Then we couldn't find the road we were looking for... seems that Google Earth's "less than 3-years old" satellite photography policy doesn't cut it for navigation in a rapidly developing China.

Yet eventually we found the "mysterious" chalk mine we were looking for, the first clue that we were somewhat on track... our second clue was a sign warning that we were entering an active military zone. Yikes! At that point we should have been very close to our first two targets, but we searched and found nothing. Still, we forged eastward and suddenly off to the left I spotted something white and very out-of-place on the brown surface of the desert. Closer inspection revealed what should have been our third target... but hey, we were happy to find anything! After that, finding the other targets was a piece of cake: