« September 2006 | HOME PAGE | November 2006 »

October 31, 2006

No Tibet Travel Permit? No Problem.

I'll keep this short and informative, with the hope of saving some of you a big chunk of cash. Since the opening of the train line to Tibet this summer, a lot of people (including myself) have made the very comfortable journey to Lhasa by rail. The tracks are smooth, the scenery is stunning, and the price is right... except for one little detail. A f#%&@! bulls@*& piece of paper known as the Tibet Travel Bureau (TTB) permit that can cost as little as Y200 (in Chengdu, I've heard) but will more likely end up setting you back between Y800 and Y1000. Most people say that it's an expensive bureaucratic necessity... but is it really necessary?

I'll keep this short and informative, with the hope of saving some of you a big chunk of cash. Since the opening of the train line to Tibet this summer, a lot of people (including myself) have made the very comfortable journey to Lhasa by rail. The tracks are smooth, the scenery is stunning, and the price is right... except for one little detail. A f#%&@! bulls@*& piece of paper known as the Tibet Travel Bureau (TTB) permit that can cost as little as Y200 (in Chengdu, I've heard) but will more likely end up setting you back between Y800 and Y1000. Most people say that it's an expensive bureaucratic necessity... but is it really necessary?

The answer is no. In fact, if you're travelling by train it's downright foolish to fork over that much cash, essentially for nothing. Here's a way to get around the TTB permit. The truth is, you only need a TTB permit to purchase your train tickets. After that, no one cares or will ever ask you to see the document... not on the train, not in Lhasa, not at Everest Base Camp. Nowhere. You should think of it less as a permit for travel and more as a voucher to wait in line at the train station. If you don't want to add 100%-600% to the price of your transportation to Tibet, here's a simple solution: get a Chinese person to buy your ticket for you. You may be able to find a friend to do this, or you may have to pay a migrant worker (failed attempt) or restaurant owner (successful attempt) to buy them like I did in Golmud. (I paid him a Y150 helper's fee for purchasing two tickets). In any case you'll end up saving a lot in the end.

The answer is no. In fact, if you're travelling by train it's downright foolish to fork over that much cash, essentially for nothing. Here's a way to get around the TTB permit. The truth is, you only need a TTB permit to purchase your train tickets. After that, no one cares or will ever ask you to see the document... not on the train, not in Lhasa, not at Everest Base Camp. Nowhere. You should think of it less as a permit for travel and more as a voucher to wait in line at the train station. If you don't want to add 100%-600% to the price of your transportation to Tibet, here's a simple solution: get a Chinese person to buy your ticket for you. You may be able to find a friend to do this, or you may have to pay a migrant worker (failed attempt) or restaurant owner (successful attempt) to buy them like I did in Golmud. (I paid him a Y150 helper's fee for purchasing two tickets). In any case you'll end up saving a lot in the end.

It's a solution that underage people all over the world have employed outside of liquor stores, and it can work for you at at a Chinese train station. Of course, you should be careful about to whom you give your money and that they don't run off on you... but the risk is certainly worth the reward. In fact, I think not paying the outrageous fees for obtaining a TTB permit is your duty. What kind of real travel permit can only be purchased at profit-hungry travel agencies, anyway? If the Chinese really wanted to regulate foreigners going into Tibet, wouldn't applying for a travel permit be similar to applying for a visa? Why does getting a Tibet Travel Bureau Permit feel so sleazy?

Feel free to send me some of the money you save. Good luck!

You can view photos of the train journey to Lhasa in the Tibet gallery.

posted October 31, 2006 at 12:25 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (81)

October 29, 2006

Chinese Wine

I missed the China Law Blog's first post about Chinese wine two weeks ago, but the follow-up post today caught my eye. That's mainly because it contains the word "Xinjiang" and Technorati alerted me... but hey, that's how these things happen. I figure I'll throw my two cents into the discussion.

Here's what I know. It's true that wine is being produced in China by the tanker-load. Most of this wine is of very poor quality, and tastes something like grape Kool-Aid mixed with grain alcohol. It sort of looks like wine, but really isn't. (Beats baijiu, though.)

There are, however, a few decent Chinese wines. All of the good ones that I've tried were made in Xinjiang, which makes sense because this is grape-central... and also because I live here. To name the few that I can recall, there's Suntime, with a passable Cabernet Sauvignon; Yizhu, located in Yili and specializing in ice wine; and the French-owned Les Champs D'or, which gets my award for the best overall winery in China. (Someone told me they use prison labor, but we're talking about wine not human rights here.) Located only forty-five minutes north of Korla, I stopped in at the Les Champs D'or production compound for a peek last month and took a few snapshots:

I don't know about you, but I'm thinking a good Xinjiang red would go very nicely with some quality Uyghur food.

posted October 29, 2006 at 09:54 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (43)

October 28, 2006

One Baadasssss Uyghur!

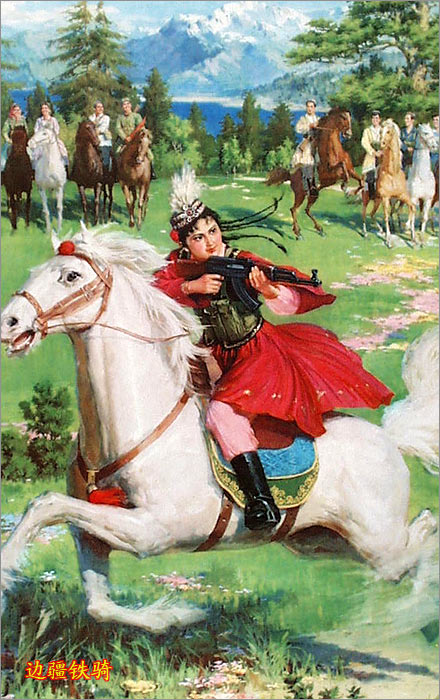

There was a time — 1978, according to my sources — when Beijing's brilliant propagandists were happy to put a machine gun in Uyghur hands to showcase China's far-flung minorities as willing defenders of the People's Republic. Simply titled "Frontier Cavalry" (边疆铁骑), I doubt we'll see any images like this again in the near future, as the Chinese government is happier now for Uyghurs to be seen as happy, simple farmers... far, far away from deadly weapons of any kind.

So, without further ado, let me present to you the lethal lady who is now the official mascot of The Opposite End of China:

Is she the most bad-ass Uyghur girl ever devised or what? (That fellow in back is certainly excited.)

Much thanks to Stefan Landsberger — who maintains an excellent collection of Chinese propaganda posters over at the International Institute of Social History — for hooking me up with this image. But the real question is... can you get me this girl's phone number? Va-va-voom!

posted October 28, 2006 at 10:30 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (33)

October 25, 2006

That Ol' Hotan Rhythm

Yesterday being the Muslim festival of Roza Heyt (known as Eid elsewhere), I decided to take a walk through the Uyghur marketplace here in Korla to see if anything intersting was going on. Unfortunately, I found out that I'd missed a meshrep in the morning. But still, there were more people out on the street than one usually finds on a Tuesday night... eating kebabs, playing pool, listening to music, and generally relaxing after a month-long fast.

I stopped in at my usual Uyghur VCD shop, where I noticed a somewhat frenzied crowd gathered around a cardboard box. So, I asked the shopkeeper what was going on:

Me: What's going on here?

Him: A new VCD just arrived from Hotan! It's the kind of traditional dutar music that farmers like.

Me: Really? That must be good then.

Him: Yeah, and it's only ten yuan. That's why everyone is buying.

Not wanting to be left out of this hysterical buying frenzy, I plunked down Y10 and ran home with my newly acquired treasure in the breast pocket of my windbreaker.

These two videos by Dolkun Omer are much more traditional than what I usually feature, so I hope you enjoy. Here then, are the sounds that have been rockin' farmers across Xinjiang — from Hotan to Gulja, from Kasghar to Qarkilik — these past few post-Ramadan days:

Happy Roza Heyt to all the Uyghurs out there!

posted October 25, 2006 at 04:43 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (13)

October 24, 2006

Xinjiang News for 2006.10.24

A special Rouzijie (Eid ul-Fitr) edition of the Xinjiang News:

A special Rouzijie (Eid ul-Fitr) edition of the Xinjiang News:

LA Times: Uyghurs feel the long arm of Beijing

Beijing bars mullahs from using loudspeakers, one of dozens of rules critics say are designed to mute Islam's voice in China, particularly among the Uighur minority here in the far-western region of Xinjiang, which the government considers a separatist threat.

Signs and banners at mosque entrances in Hotan, Kashgar and other western cities make it clear who is boss.

"Completely abide by the Communist Party's religious policy," reads an oversized banner straddling the gate of Hotan's Imam Asim tomb, half a mile over desert dunes from the nearest road. "Actively lead religion toward a just socialist society." (link)

SCMP: Chinese Muslims jump hurdles on the road to Mecca

Magied Alshamry, the head of the visa section at the Saudi Arabian embassy in Beijing, is also upset by the quota.

"I'd love to grant visas to everyone who comes to us, but they won't be able to leave China when they go to the airport without a permit from the Islamic Association. It's an embarrassment to us. It's a waste of my time and of our visas. The haj pilgrimage is for every Muslim in the world." (link)

FT: Central Asian border woes

As he waved a bottle of clear spirits containing red berries and the carcass of a small snake, the Kyrgyz border guard's sign language was very clear: next time truck driver Cai Chaojun crossed from China, he should bring more of the same medicinal drink.

Such demands from underpaid officials for contributions in cash or kind are just one of the difficulties facing people who carry goods or do business across the borders of Central Asia. (link)

CIDN: Second cross-desert highway near completion

According to October 20th reports, the roadbed construction of the second desert road in Xinjiang, which crosses the Taklimakan Desert, was completed at the beginning of July 2006. Currently, more than 240km of asphalt road surface have been completed, with the construction progress 5 months ahead of schedule. The 423.5km-long road starts from Alaer in the North and terminates at Hetian in the South, involving a total investment of RMB1.05bn. (link)

You can read the full articles below.

Muslims feel the long arm of Beijing

In Xinjiang, which is of strategic importance to China, Uighurs try to maintain their culture despite strict oversight.

Mark Magnier

23 October 2006

Los Angeles Times

HOTAN, CHINA -- Mullah Masude, 63, removes his shoes and gingerly navigates an expanse of cheap carpeting in the Jaman mosque's main worship area before climbing a set of rickety steps to the roof.

Powered by a good set of lungs and lots of practice, the cleric belts out the afternoon call to prayer. Despite his best efforts, the chant is all but drowned out by the din of a single-stroke tractor engine and a passing bus.

Beijing bars mullahs from using loudspeakers, one of dozens of rules critics say are designed to mute Islam's voice in China, particularly among the Uighur minority here in the far-western region of Xinjiang, which the government considers a separatist threat.

Signs and banners at mosque entrances in Hotan, Kashgar and other western cities make it clear who is boss.

"Completely abide by the Communist Party's religious policy," reads an oversized banner straddling the gate of Hotan's Imam Asim tomb, half a mile over desert dunes from the nearest road. "Actively lead religion toward a just socialist society."

More than 2,000 miles to the east, Beijing seems a world away, which partly explains officials' deep-seated fear that the region's more than 8 million Uighurs will unite to form an independent state.

Mutton and flat bread trump pork and rice as the cuisine of choice, blue eyes and light skin are common, and many people speak only a few words of Mandarin.

Although most Uighurs are proud of their history, distinct language and centuries-old culture, they tend to see a Uighur homeland as a distant dream, given Beijing's tight grip and economic clout.

"I'm not in favor of it, nor do I think it's possible," said Elham Adl, 22, a Uighur tour guide in Dushanzi, a town in northern Xinjiang. "I don't want to see Xinjiang become a second Iraq. And if Xinjiang became independent, we'd lose access to China's big market."

But Beijing isn't taking any chances, critics say, and it continues to intimidate the clergy, weaken Uighur culture through assimilation policies and otherwise stifle dissent.

The strategy has been successful, largely putting an end to the bombings, protests and unrest of the 1990s, though some say China has only driven resentment underground.

"They put out the fire," said Dru C. Gladney, an anthropologist and president of Pomona College's Pacific Basin Institute. "But the embers are smoldering. And unless they address hearts and minds, it will flare again."

The government's iron grip underscores Xinjiang's strategic importance. The region has huge reserves of oil, gas, gold and uranium. It is home to the nation's Lop Nor nuclear testing facility.

With 17% of Chinese territory but just 1.5% of its people, Xinjiang is an important release valve for population pressures. It's a buffer against rival Russia. And any loosening would set a precedent for pro-independence movements in Taiwan and Tibet.

"Xinjiang is very important to China's security," said Raphael Israeli, a fellow at the Truman Research Institute at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. "They will have to do what it takes when a rebellion becomes evident."

In the meantime, Beijing is working to soften local hearts and minds to its position, albeit in a sometimes heavy-handed manner.

'Love the motherland'

Ayinoor, a Uighur civil servant in her early 20s, is required to attend ideology classes for two hours a day aimed at hammering home the glories of the Communist Party, the danger of separatism and the benefits of national unity. Like others interviewed, she declined to give her family name for fear of losing her job.

If lecturing doesn't win her over, there's music, including a version of the party's recent "Eight Virtues and Eight Shames" campaign that she's required to sing, with such lines as "It's most glorious to love the motherland, a great sin to harm her." There's economic incentive: If she doesn't do well on a weekly political thought quiz, her pay is docked.

"I'm only telling you this," she said in the shadow of the historic Id Kah mosque in Kashgar, near two police cars and an army truck and a sign that read, "All ethnic groups warmly welcome the party's religious policies."

"At work I have to say, 'I love everything Han Chinese' or I get into trouble," she said, referring to the majority ethnic group.

Uighur clerics had ignored the ban on government employees entering mosques. But religious authorities started threatening their jobs as well. Now they report on attendees, who risk losing their jobs or worse. More than 300 Uighur civil servants have been jailed in recent years for their beliefs, locals say, and some were beaten to death.

Government officials were not available for comment, and the figure could not be verified.

Beijing's longer-term goal is to create a new generation of Mandarin-speaking Uighurs with fewer ties to Islam or traditional Uighur culture, critics say, including programs that send the brightest young Uighurs to Mandarin-only schools in other provinces.

"Chinese is very difficult, but it's the language of the marketplace," said Shiaili, 14, a student in Urumqi. "I've studied for two years. Sometimes I forget some of my Uighur."

Government officials did not respond to written requests for an interview. But Chinese minority and ethnic affairs officials in the past have denied trying to dilute Uighur culture and say they're raising living standards and spurring entrepreneurship, as seen, they say, by an economy that has grown forty-twofold since 1955.

But government officials also promise to remain vigilant. They blame separatist groups for more than 200 terrorist attacks since 1990, resulting in 162 deaths and more than 440 injuries.

"In Xinjiang, the separatists, religious extremists and violent terrorists are all around us," Wang Lexiang, Xinjiang's deputy chief of public security, said in August. "In China, endangering national security is the No. 1 crime. We have to crack down on it severely."

The Sept. 11 attacks gave Beijing a new argument, allowing it to tar pro-independence Uighurs as radical Muslims with ties to Al Qaeda, claims that are viewed with skepticism.

"China saw 9/11 as the best opportunity since 1949 to crack down on Uighur people," said Alim Seytoff, general secretary of the Washington-based Uighur American Assn., which advocates the creation of an independent state called East Turkistan through nonviolent means. "China makes allegations that can't be proven, but after 9/11 it's very hard to champion your cause if you're Muslim."

Wary of the link between religion and politics, China prohibits anyone younger than 18 from entering a mosque or receiving a Muslim education.

"I don't know if it's right or wrong, but it's the law," said Sulika, 43, a former soldier turned fruit seller, chomping down on a stew of sheep organs and intestine casings stuffed with rice.

Schools also require students to eat during Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of fasting and atonement. "If they don't eat, they get disciplined by the teachers," Sulika said.

Religious study for prospective clerics and others older than 18 must take place in heavily monitored government schools and after an extensive background check. At that age, many young Uighurs don't bother, having been seduced by video games and modern distractions.

"By that time, most aren't interested," said Ma Xueliang, a Muslim cleric at the Qinghai mosque in Urumqi.

If persuasion and distraction don't work, there's brute force. Xinjiang is riddled with informants, human rights activists say, amid claims that 1,000 Uighurs were executed and more than 10,000 imprisoned during a 1996-97 crackdown. Detentions have fallen off more recently, they say, because intimidation tactics are working.

"Control over Xinjiang society is very minute," said Nicholas Bequelin, a China researcher with Human Rights Watch. "It's impressive and reminiscent of Soviet Union times."

New generation of mullahs

After 1990, the authorities replaced many longtime mullahs with a new generation educated in Chinese patriotic programs, and began paying their salaries directly and requiring annual license renewals.

In many parts of Xinjiang, mullahs are required to clear their Friday sermons, limited to 30 minutes, with local religious affairs bureaus and are punished for deviating from the script. Those who resist Chinese policy, by arguing, for instance, against abortion or family planning policies on religious grounds, are fired or jailed.

"My neighbor, an imam, was arrested 12 years ago for saying something the government didn't like," said one Uighur government worker, who asked not to be identified. "He's still in jail. Their message is clear: Keep your mouth shut."

In addition to its internal campaigns over the last decade, Beijing has tried to cut off links with ethnic Uighurs in neighboring countries by pushing for extradition treaties with Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

"China has been very successful at portraying Uighurs as terrorists and themselves as victims of terrorism, while they manipulate Islam through their control over mosques," Seytoff said. "It's really not easy trying to stand up to such a powerful country and an emerging superpower."

mark.magnier@latimes.com

Hurdles on the road to Mecca for mainland Muslims

A new deal on visas between China and Saudi Arabia is set to squeeze the number of Chinese pilgrims headed for Mecca, writes Kristine Kwok.

24 October 2006

South China Morning Post

Arzuguli Saidulla closed her hardware store in Urumqi , Xinjiang , early last month and left home on the journey of a lifetime for most Muslims - her first haj pilgrimage to Mecca.

But before arriving in Islam's holiest city, the 42-year-old and more than 5,000 other pilgrims from the northwestern region first headed to Pakistan. They were following in the footsteps of many other Xinjiang Muslims, who have routinely obtained Saudi Arabian visas from the kingdom's embassy in Islamabad before the annual pilgrimage.

This year it took much longer for the Chinese Muslims to get their visas. Ms Saidulla, a mother of one, finally got her visa on October 14.

"It was so tiresome that we had to go to the embassy every day to wait for the visa," Ms Saidulla said from Rawalpindi, near Islamabad. "There were so many people."

The long wait was the result of a change in policy after the Chinese and Saudi governments agreed in May that all Chinese passport holders on the haj must go through the official channels organised by the mainland's government-sanctioned Chinese Patriotic Islamic Association, instead of a third country.

This meant pilgrims should collect visas through the Saudi embassy in Beijing and a permit from the Chinese Patriotic Islamic Association.

Upset by the refusal of the Saudi embassy in Islamabad to issue them with visas, the Xinjiang Muslims, some of whom arrived in Pakistan as early as August, protested outside the embassy for weeks until the Saudi government relented on October 3 and said visa requests would be processed in Pakistan again this year - for the last time.

"We were thrilled by the announcement, I never thought going on the haj could be this tedious," Ms Saidulla said. She finally set off for Saudi Arabia on October 15.

An official from the Islamic branch of the mainland Ministry of Religious Affairs, who gave his surname as Ma, said the new policy was designed to weed out "illegal snakeheads" who were making money by organising haj tours. "Haj is a religious activity, it should be organised by a religious organisation," he said.

But the Washington-based Uygur American Association said the change of policy could be a way to control the number of Uygurs undertaking the pilgrimage.

"Or it could be a measure to more effectively monitor who is going on pilgrimage," the association said in a statement.

Li Jinxin , a researcher from the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences, said that by requiring the pilgrims to travel in government-organised groups, the authorities were also trying to prevent the Muslims from contacting undesirable foreign influences, such as terrorists, extreme religious groups and pro-independence groups.

"There have been cases that when some Xinjiang Muslims went on the haj by themselves or through underground groups, they built up contacts with those people. This has caused concern in the government," he said.

Considered the world's biggest Islamic event, the haj attracts millions of pilgrims from around the globe to Mecca every January. The Koran says that every able-bodied Muslim should make the pilgrimage at least once in their lifetime if they can afford to do so.

Ms Saidulla is among a surging number of Chinese Muslims joining the Mecca pilgrims as China's economic boom helps to lift their living standards.

In the 1980s, Professor Li said, only a few hundred Muslims from Xinjiang would apply for a visa each year through the Patriotic Islamic Association. That figure had jumped to around 10,000 in recent years, he said.

But the surge in demand had been confined by a quota imposed by the Patriotic Islamic Association, which allowed only about 2,000 Xinjiang Muslims to go on the haj last year, Professor Li said.

The limited seats had sent would-be pilgrims, especially those without official connections, in search of visas in third countries such as Pakistan and Thailand.

"In the past, it was economic hardship that put people off from performing the pilgrimage. Now a lot more people have the financial ability to do so, but they still find it difficult to go to Mecca because of the quota imposed by the Islamic Association," Professor Li said. He said that in some cases those wishing to make the pilgrimage had to bribe the authorities to get a visa.

"Some people have complained to me that they were rejected by the Islamic Association five years in a row," he said.

Magied Alshamry, the head of the visa section at the Saudi Arabian embassy in Beijing, is also upset by the quota.

"I'd love to grant visas to everyone who comes to us, but they won't be able to leave China when they go to the airport without a permit from the Islamic Association. It's an embarrassment to us. It's a waste of my time and of our visas. The haj pilgrimage is for every Muslim in the world." But Mr Ma from the Ministry of Religious Affairs denied the mainland had ever imposed a quota.

He said the official Muslim population in China was around 21 million and the quota would be imposed only when applications reached 20,000.

The Chinese Patriotic Islamic Association had received up to 9,000 haj visa applications so far and the eventual figure was expected to top 10,000, Mr Ma said.

About 6,900 mainland Muslims performed the pilgrimage through the association last year, he added.

Professor Li said most Chinese haj pilgrims were Muslims from Xinjiang and members of the Hui minority, who preferred to apply for visas in Thailand.

Xinjiang Muslims have been collecting their Saudi visas in Pakistan since as early as 1980s, before China established diplomatic relations with Islamabad in 1990, according to Abdulla Ahmad, a Xinjiang native who is now a business consultant in Beijing.

By going to a third country, Chinese Muslims could travel to Mecca without a permit from the Chinese Patriotic Islamic Association and avoid expensive tour packages provided by the authorities, he said.

"Most of the haj pilgrims are from southern Xinjiang, and most of them are impoverished and poorly educated. They think it will be cheaper to go through unofficial channels via Pakistan," Mr Ahmad said.

"But it doesn't necessarily save them money because they are sometimes ripped off or cheated."

Ms Saidulla said she would rather have got her visa in Beijing.

"They didn't tell me about this when I collected my visa to Pakistan in Beijing. If I knew about this I would definitely apply for a Saudi visa in Beijing. That would have saved me a lot of time and I wouldn't be away from home for such a long time," she said.

Mr Ahmad, who plans to go on the haj in the next few years, said the new policy would make it safer for the pilgrims.

"Most Chinese Muslims can't speak the local language in Mecca, and some have never travelled abroad. It happens a lot that they get lost there," he said.

Snake wine helps keep border traffic flowing

Repairing crumbling roads across central Asia is only half the battle in creating a transport network for the region.

By MURE DICKIE

23 October 2006

Financial Times

As he waved a bottle of clear spirits containing red berries and the carcass of a small snake, the Kyrgyz border guard's sign language was very clear: next time truck driver Cai Chaojun crossed from China, he should bring more of the same medicinal drink.

Such demands from underpaid officials for contributions in cash or kind are just one of the difficulties facing people who carry goods or do business across the borders of Central Asia.

Poor road conditions pose another problem for Mr Cai and his heavy truck on their weekly trips into Kyrgyzstan from Kashgar city in China's far-western region of Xinjiang.

"The road is terrible," he says. "Up in the mountains, when we have a load we sometimes cannot move at all because of all those big rocks and sand."

Removing obstacles to trade, tourism and investment has become a central development challenge for Central Asia, a strategic and cultural crossroads that is one of the world's poorest regions.

In a report last year, the United Nations Development Programme said closer co-operation among Central Asia's former Soviet states could raise incomes by 50-100 per cent over 10 years.

Better transport links are top of the agenda for the Central Asia Regional Economic Co-operation forum (Carec), which groups Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Azerbaijan, along with China and Mongolia.

The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union left many Carec members struggling to maintain their basic infrastructure. New borders cut across roads and railways, prompting scarce resources to be poured into new internal routes.

Now, however, making Mr Cai's life easier is an international priority: the road he travels has been identified as an important corridor linking China with the Kyrgyz second city of Osh and reaching on to neighbouring Uzbekistan. Some progress has already been made. The road's first 18km within Kyrgyzstan is smooth going, thanks to a Rmb60m (Dollars 7.6m, Pounds 4m, Euros 6m) "rehabilitation" project last year paid for by China. There are plans for similar work on stretches near Osh. But much of the trip to the Chinese border remains a bone-jarring high-altitude trial for travellers and a harsh test for any truck and its load.

Still, the adoption last week by Carec of a "Comprehensive Action Plan" should help to secure funds to repair the most difficult stretches, cutting travel times by more than half.

Kubanychbek Mamaev, Kyrgyz deputy minister for transport, is hoping for loans from China and a deal that would see Beijing pay rehabilitation and maintenance costs in return for mineral rights.

Recent rehabilitation work on the highway between Osh and the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek were so successful, Mr Mamaev says, that he now has a new problem on the route: speeding.

"The only worry is how to reduce the number of accidents," he says.

As Mr Cai's snake wine experience suggests, however, repairing roads will be only half the battle. Carec is also seeking to smooth cross-border traffic by addressing such "software" problems as poorly run borders, divergent transport rules and unpredictable tariff regimes.

Attempts to smooth traffic between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, for example, have faced a number of obstacles.

For a few days after the introduction of high-tech equipment at one customs post, trucks were "just flying across the border", says an Asian Development Bank official.

"But then (border officials) started to realise they were not making any money and things started to break down," he says.

Similar problems could threaten the gains from construction of a planned new customs post on the Osh-Kashgar road that is to be largely funded by Beijing.

Travellers already contend with multiple checkpoints - including one set up by officers of China's People's Liberation Army that, local Chinese border guards suggest, should not exist at all.

Border closures for long lunches, national holidays and bad weather bring many shipments to a standstill. Kyrgyz officials say China maintains a ban on foreign vehicles within its borders, a stance that could reduce future willingness to allow passage to Chinese trucks.

As for Mr Cai, he says he now plans to bring a batch of snake wine on his next trip across the border.

Even if the usual small cash contributions prove enough to smooth their passage, however, he and his comrades still have a lot of hard travelling ahead.

Construction of Second Desert Road in Xinjiang Accelerated

23 October 2006

China Industry Daily News

According to October 20th reports, the roadbed construction of the second desert road in Xinjiang, which crosses the Taklimakan Desert, was completed at the beginning of July 2006. Currently, more than 240km of asphalt road surface have been completed, with the construction progress 5 months ahead of schedule. The 423.5km-long road starts from Alaer in the North and terminates at Hetian in the South, involving a total investment of RMB1.05bn.

posted October 24, 2006 at 02:16 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (32)

October 23, 2006

Mildred Cable's Northwest China

"The Gobi Desert" — written by English missionary Mildred Cable and first published in 1942 — is an account of travels in northwest China during a very different era. The book, which describes Cable's journeys through Gansu and Xinjiang (then still called Turkestan) between 1923 and 1936 is filled with descriptions of the Turki (Uyghur), Mongol, Tungan (Hui), Kirghiz (Kyrgyz), Uzbek, Tibetan, Russian, and Qazaq (Kazakh) people who each ethnically dominated their own small region before the post-liberation hyper-influx of Han migrants. The book is a fun read, both for its humorous descriptions of local peoples and for its politically incorrect "heathens-just-don't-understand" moral tone. Here, for example, is an excellent description of Xinjiang's Uyghur donkey drivers:

"The Gobi Desert" — written by English missionary Mildred Cable and first published in 1942 — is an account of travels in northwest China during a very different era. The book, which describes Cable's journeys through Gansu and Xinjiang (then still called Turkestan) between 1923 and 1936 is filled with descriptions of the Turki (Uyghur), Mongol, Tungan (Hui), Kirghiz (Kyrgyz), Uzbek, Tibetan, Russian, and Qazaq (Kazakh) people who each ethnically dominated their own small region before the post-liberation hyper-influx of Han migrants. The book is a fun read, both for its humorous descriptions of local peoples and for its politically incorrect "heathens-just-don't-understand" moral tone. Here, for example, is an excellent description of Xinjiang's Uyghur donkey drivers:

For local journeys, or when, owing to the perishable nature of the cargo time is of great importance, the Turki with his drove of little donkeys is the man. He is met on every road of Turkestan, always hustling his beasts through a cloud of dust and lashing them right and left to keep them up to speed. He is a great burly fellow, dressed in loose clothes which increase his bulk, and his baggy trousers are stuffed into high leather boots. His chapan (coat) is tied in with a thick belt, and he wears a round hat with a sheepskin border which mixes with his loose hair to form a shaggy frame to the weather-beaten face.

He mainly conveys melons, early vegetables and fruit — apricots, peaches, grapes and pears according to the season.... He knows no organization of travel life, but pushes on from stage to stage with restless energy. When the donkeys must be fed he drives them to an inn-court, tosses the panniers from their backs, carelessly throws fodder into the manger, pulls some hard cakes of bread from his own food-bag and sits down to a meal of bread soaked in tea. Being a Moslem, he will buy nothing from a kaper (infidel), so himself carries what he will need to eat on the road.

The donkeys are small and cheap, so he is careless of life and sacrifices them in large numbers to his passion for speed and his reckless output of strength. He will use dangerous short-cuts over which no other class of transport-man will venture, and in bad weather many beasts die by the roadside. This does not trouble him... He will normally do five full stages in three days and nothing may stand in his way, but when the goods are handed over and he can lodge in a Moslem inn he enjoys twenty-four hours of sheer luxury. There is hot, greasy pilau to eat, women to wait on him, and long carefree hours of sleep to enjoy before he starts again on the hectic return journey.

I'm not really sure that all that much has changed during the past eighty years, although donkeys are probably more expensive. Uyghur womens' contempt in general for Uyghur men — which has been conveyed to me on numerous occasions — was already quite evident in the 1930s:

The foundation of the Turki home is undisguised gratification of sensuous pleasures. The man comes home to sleep, and all the relationships of the home centre on his use of those hours of darkness. On that score he is master, and tyrannical in his use of power, for the male creation has unquestioned right of dictatorship in the Turki world. He has too many children to be deeply attached to any one of them, and when a child dies its death brings him little sorrow. As to a sick wife, the sooner she goes the better. Family relationships bring him so little of the chastening which refines and purifies character that is is not suprising that men of the Turki race remain, as their wives always declare them to be, "mere animals."

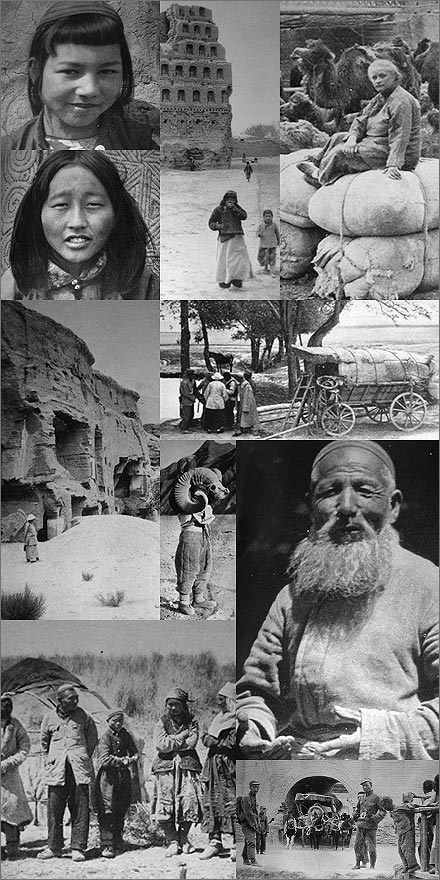

What I most want to share with you, however, are some of the pictures reproduced in "The Gobi Desert". There aren't many historical photographs of Xinjiang and northwest China available online, so I though I'd do my part here:

The original photo captions, from left to right and top to bottom are: A Turki girl; The tower of Sirkip; The inn courtyard (showing Mildred Cable); A Mongol woman at her tent door; The great facade was pierced with innumerable openings (showing Cable at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang); The worst of the desert stages were over; The horns of an ovis poli (Marco Polo sheep); One of the Khan's men; A family of Qazaqs; The city gate at Tunhwang.

The funniest aspect of Cable's narration is her frequent reference to her activities as a Christian missionary. Once can only imagine the gratitude of the desert woman in the quote below:

We were once asked to share the meal of an isolated family whose only water-supply oozed through the sand and collected at the bottom of a deep pit. For grain they were reduced to a ration of bran... steaming it carefully over a fire the desert woman made a palatable meal, which she generously shared with us. We in our turn taught her how to thank God for daily food.

Cable also can't help but remind us that the terrible plight of so many Turkis, Tungans, and even Han Chinese could easily be relieved by acceptance of Jesus Christ. Here, she describes a Uyghur fasting ritual:

For forty long days the only occupation of the fasting man was to say his ritual prayers and to enumerate the ninety-nine attributes of Allah.... I stood there awhile and let my imagination picture the stones falling ceaselessly through forty long days from the weakening fingers of this man who knew all the ninety-nine names for God but had never learnt the one which would have changed everything for him — God is love.

Ah, missionaries. You've got to give them an A for effort, but an F for cultural sensitivity. Anyway, enjoy the photos.

posted October 23, 2006 at 09:56 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (50)

October 19, 2006

Tibet Photos

The photos from my trip to Tibet have been posted to the gallery. Need I say more?

posted October 19, 2006 at 11:33 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (12)

October 16, 2006

"Shooting them like Dogs"

Let me preface this entry by reminding my readers that I love the People's Republic of China like a parent and am firmly and resolutely opposed to seperatism of any kind. Tibet is an inseperable part of the great motherland! That said...

WARNING:The video below contains graphic violence and may be disturbing to some viewers.

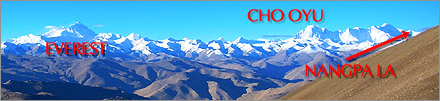

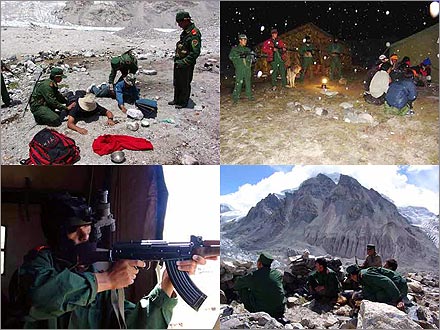

The international outrage over the shooting of Tibetan refugees attempting to cross into Nepal - which I reported on earlier this week - has intensified today with the posting of a video of the event (also here and here) on YouTube, shot by a Romanian cameraman. The killings were captured on video from the slopes of Cho Oyu at a distance of approximately 1 kilometer. The video clearly shows several of the refugees falling to the ground as PLA soldiers fire rifle shots in their direction:

From the NY Times:

Witnesses quoted by human rights groups said that those who had been fired upon included monks, women and children and that the person who had been killed was a 25-year-old Tibetan Buddhist nun.

The video does not offer a comprehensive account. It was shot from a long distance — the narrator says the cameraman was more than half a mile away — and only a few faces are clearly identifiable. But it does suggest that the shootings were not in direct response to an attack on soldiers. The refugees were spaced far apart on an arduous climb over a 19,000-foot-high pass, called Nanpa La, when the two victims fell.

You can read the full article below.

For those of you with Google Earth installed, click here to visit Nangpa La Pass, where the incident took place. Also, thanks to the reader who passed on this link to official government photos of the incident and the PLA soldiers deployed along the Tibet/Nepal border:

Video Disputes China’s Claim Shooting Was in Self-Defense

The New York Times

By JOSEPH KAHN

Published: October 16, 2006

BEIJING, Oct. 15 — A Romanian videotape that appears to show Chinese security forces shooting two Tibetan refugees in the Himalayas contradicts Beijing’s claim that the refugees were shot when soldiers acted in self-defense.

China acknowledged on Thursday that soldiers killed one refugee and wounded another on Sept. 30. The official New China News Agency said the soldiers acted only after about 70 refugees seeking to enter Nepal illegally from China attacked border troops.

The long-range video shows a slow, single-file line of Tibetan refugees climbing over a snow-covered mountain pass followed by Chinese troops. A rifle shot is heard and the first climber in the pack falls to the ground, followed by the climber at the tail end of the group.

A separate shot shows a uniformed Chinese soldier firing a rifle. It then shows several soldiers examining the shooting victims and escorting some detainees back to a camp.

The video was first shown on Pro TV, a private Romanian network, and was posted on the Internet. It was taken by Sergui Matei, a Romanian cameraman on a climbing expedition on Cho Oyu, a peak near China’s border with Nepal.

Tibetans often cross into Nepal, at least partly because their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, visits there often. He lives in exile in India and is not permitted to visit China.

The Sept. 30 incident was first reported by mountaineers in Nepal and was circulated by human rights groups, including the International Campaign for Tibet and Human Rights in China.

Witnesses quoted by human rights groups said that those who had been fired upon included monks, women and children and that the person who had been killed was a 25-year-old Tibetan Buddhist nun.

After the accusations, China’s Foreign Ministry vowed to investigate. The New China News Agency subsequently issued a report that said the soldiers had fired in self-defense after soldiers had tried to persuade the group to return home. “The stowaways refused and attacked the soldiers,” the agency said.

The video does not offer a comprehensive account. It was shot from a long distance — the narrator says the cameraman was more than half a mile away — and only a few faces are clearly identifiable.

But it does suggest that the shootings were not in direct response to an attack on soldiers. The refugees were spaced far apart on an arduous climb over a 19,000-foot-high pass, called Nanpa La, when the two victims fell.

The American ambassador in Beijing, Clark T. Randt Jr., went to the Foreign Ministry on Thursday to protest China’s treatment of the refugees, an embassy representative said.

posted October 16, 2006 at 10:57 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (18)

October 14, 2006

Xinjiang News for 2006.10.14

SCMP: Shanghaiers exiled to Xinjiang during Cultural Revolution fight for equal pensions

Although many in Shanghai volunteered, some had little choice, and others were coerced. Neighbourhood officials allowed families to keep their other children in Shanghai if they would surrender one for Xinjiang.

Many of the families who sent children had bad class backgrounds from working for foreign companies before 1949 or being labelled "rightists" in earlier political campaigns. The government blocked their children from attending university or finding good jobs. (link)

AFP: Kadeer asks Yunus to help Xinjiang's Uyghur Muslims

"I wish to congratulate him and hope he can help my people overcome poverty," said Kadeer, among 191 people nominated for the Nobel award this year. Bangladesh's Yunus, dubbed the "Banker to the Poor", and his Grameen Bank won the Nobel award Friday for helping millions escape the poverty trap through a system of small-scale loans.Kadeer, leading a struggle for eight million Uighurs in China's autonomous northwest Xinjiang, said her people were in dire need of assistance to free them from poverty, allegedly worsened by an influx of mainland Chinese. (link)

Xinhua: Wild horses fitted with collar video cameras

Przewalski's horses have existed for 60 million years, and are the only surviving wild horse species in the world. They were first known to the outside world in 1879 when Russian explorer Nikolay Przewalski discovered them in Xinjiang.

A German party captured 52 of the horses in 1890 for transport back to Hamburg, but only 28 survived the journey. The thousand or so Przewalski's horses in the world, including those in Xinjiang, are said to be the offspring of those survivors.

The horses disappeared in this westernmost region of China due to excessive poaching for meat and environmental degradation over a period of 100 years before 1986. (link)

China Daily: Xinjiang Schools Ban Hepatitis-B Carriers

The pupils were told to go home in the city of Urumqi in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

"I am in a desperate situation now; no school is willing to accept me with a drop-out paper in my hand," one student called Xiaoxiao told the Beijing News on Monday.

The 13-year-old boy was in the first grade of junior high at Urumqi No 15 Middle School six weeks ago. The school told him to return to his village three weeks later because he "carried the Hepatitis-B virus." (link)

You can read the full articles below.

Patriot pains: Shanghai citizens exiled during the Cultural Revolution are refusing to give up their fight for equal benefits

14 October 2006

South China Morning Post

When he was 17, Wang Weiguo found himself planting cotton at the edge of the Taklimakan desert in China's far western region of Xinjiang, a world apart from his home in cosmopolitan Shanghai.

The year was 1963 and patriotic zeal had prompted him to volunteer to tame the frontier. Tens of thousands of young Shanghainese heeded the government's call and went to the borderland as pioneers in the 1960s. "We were patriotic," Mr Wang said. "We were innocent. It's not like now."

More than three decades later, some returned to the city of their birth to live out their twilight years. But they feel forgotten and neglected by the government that sent them to Xinjiang , since many have been unable to secure adequate pensions.

With the same determination that allowed them to transform desolate land into productive fields, the returnees have organised a weekly protest for the past three years to seek higher benefits from the Shanghai government.

Recent revelations that corrupt Shanghai officials were stealing from the city's pension fund have increased their anger. The scandal has already ousted Shanghai's top leader, party secretary Chen Liangyu .

"We ought to receive the same treatment as Shanghai workers," one returnee said. "The government must take responsibility for its past mistakes and give us compensation."

An estimated 100,000 Shanghai "educated youth", their ages ranging from below 16 to the mid-20s, went to Xinjiang from 1963. The decision to send them was reportedly made by Wang Zhen , then a vice-premier who eventually rose to vice-president.

Shanghai was, as usual, the vanguard of the revolution. The practice of sending students and urban youth to rural areas would later grow into a political campaign known as "Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside" during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution.

"It is imperative that educated youth go to rural areas to be re-educated by the poor and lower-middle peasants. We must convince cadres and other people in cities to send their children {hellip} to the countryside," Mao Zedong wrote in a People's Daily article headlined "We Have Two Hands Too. We Will Not Loaf Around in the City".

Although many in Shanghai volunteered, some had little choice, and others were coerced. Neighbourhood officials allowed families to keep their other children in Shanghai if they would surrender one for Xinjiang.

Many of the families who sent children had bad class backgrounds from working for foreign companies before 1949 or being labelled "rightists" in earlier political campaigns. The government blocked their children from attending university or finding good jobs.

The send-offs from Shanghai were grand events. Dressed in army uniforms with Mao buttons pinned to their chests, members of the children's crusade excitedly boarded trains hauling bundles filled with food and supplies packed by worried mothers.

Arriving in Xinjiang after a week-long journey by train and truck, their idealism was quickly eroded by the rugged conditions. The soil they tilled was often barren or alkaline. Temperatures ranged from minus 20 degrees Celsius in winter to more than 40 degrees in summer.

Mr Wang and his group of nearly 200 went to an area outside Aksu city, along the old Silk Road trading route. They ate boiled turnips and slept in pits covered with tree branches and dirt. "If you were walking at night and weren't careful, you would go through someone's roof," he said.

This was life in the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, a military-linked conglomerate engaged in agriculture and industry. Popularly known as the bingtuan (soldier group), the corps encouraged migration and protected stability in the border region.

Still in existence today, it is a "state within a state", operating a system of labour camps that have drawn criticism from human rights groups.

The Shanghai contingent remained out west for years. Some escaped by sneaking back to Shanghai, fleeing to other provinces. Many died. Young women could find a way out by marrying local husbands.

Only after the Cultural Revolution and the beginning of reforms in 1978 did those sent to the countryside regain hope about the prospect of going home.

As Shanghai people sent to other parts of the country began to trickle back to the city, those in Xinjiang found their return blocked by a set of rules known by its number, Document No 91, which said the government should take steps to ensure that they stayed put.

"Take practical, feasible measures to resolutely make the vast majority of Shanghai youth remain stably in Xinjiang," ordered the document, issued by Shanghai and Xinjiang with the backing of the central government.

For Shanghai's part, this meant tactics such as detaining returnees, shutting down their small businesses and barring their children from attending local schools. This went on through the 1980s.

Various theories have circulated about why Shanghai specifically discriminated against returnees from Xinjiang, including their poor political backgrounds and the city's reluctance to accept a mass influx of people who were still needed in the western region.

In the 1990s, however, looser controls and retirement have allowed an estimated 20,000 to return to Shanghai.

Their return has highlighted a major flaw of the mainland's pension system: lack of a national scheme. Residents across the country contribute different amounts and receive different benefits, and localities manage the funds without central government oversight.

Some of the Xinjiang returnees never paid into a retirement scheme because they were working before pension reforms started. Others paid into a fund, but were unable to transfer their accounts to Shanghai.

Those who are receiving benefits from the Shanghai government have found that the levels are far below those of the city's other retired workers, since they are based on Xinjiang salaries and living standards. Mr Wang, 60, receives about 500 yuan a month - roughly half the average Shanghai level. His medical insurance adds a further 20 yuan. He relies on his children and renting his home to a retail shop to supplement his income.

He bristles at the idea of accepting poverty relief, saying he believes it denigrates his contribution to the nation. "Our slogan is that we want the same treatment given to Shanghai's retired workers," he said.

No one will openly say who organised the weekly protests, which began in June 2003. Shanghai has handled the demonstrations delicately, since the protesters are elderly and considered patriots by many. Still, authorities view the returnees as a threat to state security and make periodic arrests.

After foreign journalists stumbled on the protests in March 2004, authorities used it as an excuse to crack down. Police held reporters from the South China Morning Post and French news agency Agence France-Presse for several hours.

The following week, the city sent hundreds of riot police to clear the protest and later offered a one-off increase of 50 yuan in benefits as part of the government's dual approach to the problem. Police have since warned foreign journalists about covering the demonstrations and protesters have been cautioned about speaking to reporters. A leader of the group recently declined to be interviewed, saying: "We can handle our own internal affairs."

The protests, now held every Wednesday outside an office of the Shanghai Labour and Social Security Bureau on Hankou Road, still attract hundreds. They even play a social function, allowing retirees with shared experiences to meet and exchange information.

In the two months since the Shanghai pension scandal came to light, talk has turned to whether reforms to help their plight could follow.

Zhong Renyao , a professor at the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics who advises the government on pension reform, said the corruption case could bring change. He is calling for a move towards a unified national system and more transparency on the part of local governments over how the funds are invested.

Ideally, the central government would take control of local pensions, but some provincial and city level officials would oppose such a move, the professor said. As a halfway measure, the central government could set uniform rates for pension contributions and benefits. "This is entirely possible," he said.

In the meantime, the Xinjiang returnees cling to the hope that they might one day receive better treatment. Lawyers have refused to take on their case, so they have launched a letter-writing campaign to ask the Supreme People's Court to accept a lawsuit.

"If we want to eat, we have no money to see a doctor. If we see a doctor, we have no money to eat," one letter said. The court hasn't responded.

Xia Lin , who spent more than 30 years near Korla city farming and doing menial labour before returning to Shanghai in 1996, said he hoped the group's contributions to the nation would be recognised.

He wants someone to write the complete history of Shanghai youth sent to Xinjiang, but the topic is still too sensitive. One returnee, Xie Mingan , has written a trilogy, Bitter Love, about his personal experiences. The work had a limited printing. Overseas, stories of young people who were "sent down" to the countryside are reflected in works such as the memoir Spider Eaters by Rae Yang and a movie directed by Joan Chen, Tian Yu, about a teenage girl who compromises herself in an attempt to return home.

Mr Xia, who is self-taught with only a middle school education, is the scribe of the group. He spends his days writing articles about their plight and letters to various government bodies.

He doesn't feel up to the task of writing a history, but he says the work should gather the collective experiences of the returnees. "This is a history of the government using forced labour," he said.

Some names have been changed.

Chinese dissident asks Nobel award winner to help Uighur Muslims

13 October 2006

Agence France Presse

WASHINGTON, Oct 13, 2006 (AFP) -

US-based Chinese dissident Rebiya Kadeer on Friday asked Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus to help introduce his successful poverty eradication concept among minority Uighur Muslims in China.

"I wish to congratulate him and hope he can help my people overcome poverty," said Kadeer, among 191 people nominated for the Nobel award this year.

Bangladesh's Yunus, dubbed the "Banker to the Poor", and his Grameen Bank won the Nobel award Friday for helping millions escape the poverty trap through a system of small-scale loans.

Kadeer, leading a struggle for eight million Uighurs in China's autonomous northwest Xinjiang, said her people were in dire need of assistance to free them from poverty, allegedly worsened by an influx of mainland Chinese.

The 58-year-old grandmother spent six years in prison in China before she was deported in March last year to join her family in the United States.

Before her arrest, Kadeer was a millionaire businesswoman and her businesses were a source of training and employment for fellow Uighurs. Her companies have come under constant harassment from the Chinese authorities and are now on the verge of collapse.

About 100,000 Uighurs, including her three sons, are languishing in jail for their political and religious beliefs.

Kadeer was nominated by a Swedish parliamentarian for "championing" Uighur rights and for being "one of China's most prominent advocates of women's rights."

China Exclusive: Wild horses protected with collar cameras

13 October 2006

Xinhua News Agency

URUMQI, Oct. 13 (Xinhua) -- Inside Karamay Nature Reserve, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, a herd of Przewalski's horses are roaming around a pond, while the lead mare swings her tail leisurely.

That is a picture broadcast from a camera attached to a collar around the mare's neck, said Cao Jie, director of Xinjiang Wild Horses(Przewalski's Horses) Propagation Center.

On Sept. 30, research workers from the United States, Germany and China collared a mare and a stallion from two separate groups of Przewalski's horses inside Karamay Nature Reserve, in the Junggar Basin.

The collar cameras are the first of their kind in China, says Cao, who heralds the move as a crucial step in releasing the horses into the wild.

The center is considering putting the collars on the remaining lead mares of four more herds the center has released.

Przewalski's horses have existed for 60 million years, and are the only surviving wild horse species in the world. They were first known to the outside world in 1879 when Russian explorer Nikolay Przewalski discovered them in Xinjiang.

A German party captured 52 of the horses in 1890 for transport back to Hamburg, but only 28 survived the journey. The thousand or so Przewalski's horses in the world, including those in Xinjiang, are said to be the offspring of those survivors.

The horses disappeared in this westernmost region of China due to excessive poaching for meat and environmental degradation over a period of 100 years before 1986.

To bring Przewalski's horses back to Junggar Basin, their natural habitat, the Chinese government has included them in a protection scheme for eight endangered animal species.

The Xinjiang Wild Horses (Przewalski's Horses) Propagation Center opened in 1986 with the import of 18 horses from the United States, Britain and Germany.

The center keeps 290 horses, most of them in captivity. It started to release the horses into a semi-wild environment in 2001 and so far 45 horses have been released into the hilly areas around Karamay.

Eighteen colts have been born to six herds in the semi-wild environment.

However, some of the wild horses have gone astray and died. Herders were hired to look for missing horses, says Cao.

"With the collar cameras in place, it will be easier for us to track the six herds in the semi-wild environment," says Cao.

The two collars were donated by the Smithsonian's National Zoo, in Washington, DC, and the Cologne Zoo, Germany.

Previously, tracking and monitoring was done manually, with the help of telescopes and a jeep, he says.

"Information flashed back will not only enable research workers to respond immediately when a herd encounters misfortune, but will also be of great value to drafting of new development plans for the horses," says Cao.

No releases are planned this year because of a lack of suitable ground, but the collar cameras are helpful in finding locations.

It is expected more wild horses will be released next year.

Like most endangered species, the wild horse is facing the problem of hereditary degeneration due to inbreeding and long captivity.

Six Przewalski's horses were imported from Germany to vary the gene pool last year, says Cao.

Xinjiang Schools Ban Hepatitis-B Virus Carriers

By Xie Chuanjiao

11 October 2006

China Daily

Nineteen junior high school students have been told to leave school after they were found to be carriers of the Hepatitis-B virus.

The move has caused controversy among those who say the ban goes against the youngsters' rights.

The pupils were told to go home in the city of Urumqi in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

"I am in a desperate situation now; no school is willing to accept me with a drop-out paper in my hand," one student called Xiaoxiao told the Beijing News on Monday.

The 13-year-old boy was in the first grade of junior high at Urumqi No 15 Middle School six weeks ago. The school told him to return to his village three weeks later because he "carried the Hepatitis-B virus."

Mao Qun'an, a spokesman for the Ministry of Health, blasted the decision to ban the pupils.

"This is prejudice. All these students can go to school unless they are sick enough to be hospitalized."

The Hepatitis-B virus, like the HIV virus, is mainly transmitted through sexual contact and blood.

It cannot be spread through food or water, sharing eating utensils, breastfeeding, hugging, kissing, coughing, sneezing or by casual contact.

China is believed to have more than 120 million Hepatitis-B virus carriers.

Most people who become infected get rid of the virus within 6 months, but it can cause cirrhosis (scarring) of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and even death. Not everyone who tests positive goes on to develop any symptoms, although they could still be spreading the disease.

"All the seven students we sent away are Hepatitis-B virus carriers in a contagious period," Sun Xiaomei, an administrative official from the No 67 Middle School told China Daily yesterday.

"We made the decision when considering a safe environment for our other 900-plus students, including 400 that board," Sun continued.

Yin Xiuqin, from the No 15 Middle School, showed reporters a paper released in March by the Urumqi education department. It said students can be told to leave school if they have "chronically contagious diseases in a spreading period, all kinds of epidemic diseases in acute conditions and abnormal liver functions."

"We are doing things according to the rules," Yin said.

An official with the Urumqi Education Bureau who was reluctant to give his name told local media on Monday: "We have proved their cases may cause an epidemic after DNA tests. We had to tell them to leave school."

Zhang Yuexin, a senior expert from the Xinjiang Liver Disease Centre, disagreed, telling the Nanfang Daily: "There is nothing wrong with their liver functions. Viruses are duplicating inside their bodies, but do not show they are in an acute period."

"What the schools have done is not legal. Even if the students are Hepatitis-B virus carriers, they still have the right to a normal school life," a local lawyer named Zhang Yuanxin told China Daily.

China has launched a nationwide campaign calling on people not to take a biased attitude towards people carrying the Hepatitis-B virus, said Mao from the Ministry of Health.

The number of Hepatitis-B patients has become a major public health issue, sources from the ministry said.

posted October 14, 2006 at 04:22 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (20)

October 11, 2006

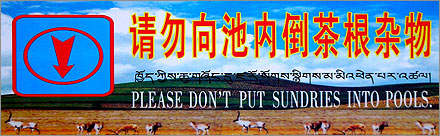

From the Chinglish Files...

Question: how is it that China can spend US$4 billion building a railroad to Tibet without allocating a few hundred bucks for a foreigner to proofread the line's English signage? The following sign is posted above the sink in trains on the Lhasa-Xining line:

Translation: don't throw your garbage into the sink. Sigh. You gotta love China!

posted October 11, 2006 at 05:25 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (15)

Bingtuan Changes

For those of you who aren't up to date on the strange way things are run here in Xinjiang, let me explain. Xinjiang, unlike other provinces in China, is effectively under the control of two governments: a normal provincial government like those found elsewhere, and the Xinjiang Production & Construction Corps... also known as the Bingtuan (兵团). The official word on the Bingtuan is this:

For those of you who aren't up to date on the strange way things are run here in Xinjiang, let me explain. Xinjiang, unlike other provinces in China, is effectively under the control of two governments: a normal provincial government like those found elsewhere, and the Xinjiang Production & Construction Corps... also known as the Bingtuan (兵团). The official word on the Bingtuan is this:

In 1949, Xinjiang was peacefully liberated. To consolidate border defense, accelerate Xinjiang’s development, and reduce the economic burden on local governments and the local people of all ethnic groups, the People’s Liberation Army units stationed in Xinjiang focused their efforts on production and construction, starting large-scale production and construction projects.

The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), established in 1954, assumes the duties of cultivating and guarding the frontier areas entrusted to it by the state. It is a special social organization, which handles its own administrative and judicial affairs within the reclamation areas under its administration, in accordance with the laws and regulations of the state and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and with economic planning directly supervised by the state. It is subordinated to the dual leadership of the central government and the People’s Government of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

While it's supposed to be subordinate to both the central and provincial governments, in reality the Bingtuan only answers to Beijing. Thus a map of Xinjiang - an autonomous region itself - should include swiss cheese holes of XPCC control compared with, say, the solid cheddar sovereignty of a Shandong or Hunan.

Anyway, I found the following headline from the October 8th edition of Ta Kung Pao (via the BBC Monitoring Service) interesting: China's Xinjiang to end separation between Production Corps, local government. What!?! Really?

No, not really:

Disputes have arisen from time to time in developing and exploiting natural resources, such as lands, prairies, water resources, and mineral deposits.In an attempt to change this situation, Xinjiang has begun to let corps leaders and local officials fill positions on each other's side. Examples: The secretary of the Party Committee of Xinjiang Autonomous Region is concurrently the first political commissar of the Xinjiang Corps. The secretaries of the Party Committees of prefectures and autonomous prefectures are concurrently the first political commissars in the corps' divisional Party Committees. The secretary of the corps Party Committee is also the deputy secretary of the Party Committee of Xinjiang Autonomous Region.

Oh, I get it. Rather than encourage a struggle between two seperate leaders to squeeze out every last jiao of bribe money and skim, Xinjiang's government and the Bingtuan have decided to combine forces in order to empower a small number of regional overlords. Those so-called "disputes"? A thing of the past... now that all the money is headed for the same fat pockets.

China's Xinjiang to end separation between Production Corps, local government

10 October 2006

BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific

Text of report entitled: "Xinjiang changes the state of separation between the Production and Construction Corps and local government", published by Hong Kong newspaper Ta Kung Pao website on 8 October

Construction is in full swing of an industrial park, so far the largest in Xinjiang - the Kuytun-Dushanzi Petrochemical Industrial Park.

This industrial park, which covers an area of 89.9 sq.km. according to the plan, is drawing wide attention from all sectors. Crossing the boundary between different administrative areas and breaking the restriction of administrative relationship in Xinjiang, this provincial-level industrial park incorporates the Kuytun City Petrochemical Industrial Park of the local government, the Dushanzi District Petrochemical Industrial Park in Karamay City under the Xinjiang Petroleum Administration, and the Petrochemical Industrial Park of the Seventh Agricultural Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.

Meanwhile, in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, the government of Shayibake District and the adjacent 104th Regiment of the 12th Agricultural Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps have announced that they will cooperate in building an industrial park on the border between their administrative areas, consisting of small processing enterprises and export-oriented industries with city industries as the main component.

With the construction of these industrial parks, people have seen with pleasant surprise that a real change is being made in the decades-old practice that the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps and the local government are working independently of each other. The dream of their cooperation in developing the region that people have cherished for decades is beginning to come true.

Back in January 1950, a 193,000-strong army of the Xinjiang Military District embarked on the task of cultivating the land while guarding the frontier. With the gun in one hand and the hoe in the other, all members of this army joined the task to meet the central authorities' demand, the only exception being the office workers and garrison units, which accounted for 20 per cent of this army.

Year after year, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps has carried on the task of guarding and cultivating the land in this centuries-old remote frontier area, making outstanding contributions to the prosperity and stability of Xinjiang and the border security of our country. It is regarded by the central authorities as the "core force for Xinjiang's stability".

The Production and Construction Corps' administrative area for carrying on its duties of cultivating and guarding the frontier land borders on that of the local government. The two administrative areas form a jagged, interlocking pattern. Also, as the corps is an entity specifically designated in the state plan, its development is independent of the local government, resulting in separation from each other. As a result, disputes have arisen from time to time in developing and exploiting natural resources, such as lands, prairies, water resources, and mineral deposits. In an attempt to change this situation, Xinjiang has begun to let corps leaders and local officials fill positions on each other's side. Examples: The secretary of the Party Committee of Xinjiang Autonomous Region is concurrently the first political commissar of the Xinjiang Corps. The secretaries of the Party Committees of prefectures and autonomous prefectures are concurrently the first political commissars in the corps' divisional Party Committees. The secretary of the corps Party Committee is also the deputy secretary of the Party Committee of Xinjiang Autonomous Region. And the members of the corps' divisional Party Committees are also the members of the Standing Committees of Party Committees of the prefectures or autonomous prefectures where they are stationed.

Source: Ta Kung Pao website, Hong Kong, in Chinese 8 Oct 06

posted October 11, 2006 at 01:45 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (41)

October 07, 2006

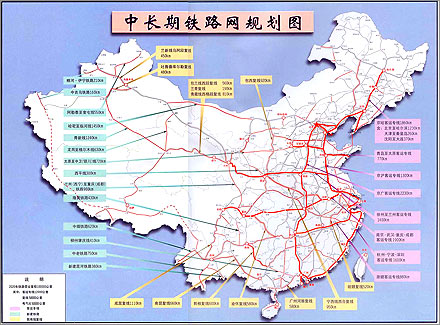

The Chinese Rail Network, Someday...

Getting from point A to point B in western China can be a pain in the ass, so it's nice to think that someday I'll be able to take a comfy train ride to almost any destination:

I was made aware of the above map - the reliability of which is uncertain and the authenticity of which is unclear - by a great link in a post over at Migrant Worker. (How'd you find that map?) The most interesting features of the plan from Xinjiang's point of view are: (1) a northern route from Hami east across Inner Mongolia that appears to shorten the length of a trip to Beijing, (2) a rail link into Kyrgyzstan from Kashgar, (3) an extension from Urumqi to the Altai Region, and (4) the route of a recently announced link from Korla to Golmud in Qinghai Province.

Perhaps most intriguing, however, is the long dotted line running south from Kashgar towards Ali and Kashgar along China's western border. If built, this railway would likely be more difficult to design and maintain than the recently opened line to Tibet. (There are several passes above 5400m along the proposed route.) Is it possible to imagine the day when - according to this map - I can get on a train in Kashgar and choose from the following list of final destinations: Lhasa (Tibet), Kathmandu (Nepal), Thimbu (Bhutan), Kunming (China), Vientiane (Laos), and Hanoi (Vietnam)?

I also notice that Hotan (和田) and the other cities along the southern Silk Road have been left without rail service in this plan. Does this mean that Hotan County - where the population is something like 96% Uyghur - will be able to maintain it's status as a relatively untouched bastion of Uyghur culture?

You can click on the small map above to download a larger version.

posted October 07, 2006 at 12:42 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (15)

October 06, 2006

Lhasa Disco

While in Lhasa recently, I supped more than once at the Tengyelink Café... best steak, tacos, and Indian food in all of Western China. But that's beside the point of this entry. While conversing with the lovely waitresses at that fine dining establishment, it was recommended to me that a delightfully entertaining evening could be found in Lhasa at a certain discotheque by the name of Neeway Nangma.

On the advice of these young women I walked the fifteen minutes from my lodgings at the Dongcuo Youth Hostel to this popular night spot on Lingkor Bei Lu. What I found there amazed me... a scene both completely un-Chinese and completely un-Western: something uniquely Tibetan and groovy. I'd recommend a visit to Neeway Nangma for anyone who's visiting Lhasa and finds the nightlife options a bit lacking in excitement. Here are two video samples of what awaits you... first, the awesome spectacle of the Tibetan disco circle:

And just to show you the diversity of the entertainment, here's some sort of quasi-traditional circle stomp that took place later in the evening:

Neeway Nangma, Lhasa's premier nightclub, is located five minutes walk northwest of the Ramoche Temple at 13 Lingkor Bei Lu... 75 meters east of the intersection with Dousenge Lu. The action takes place from 10:30pm to 4:30am every evening.

posted October 06, 2006 at 10:26 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (16)

October 05, 2006

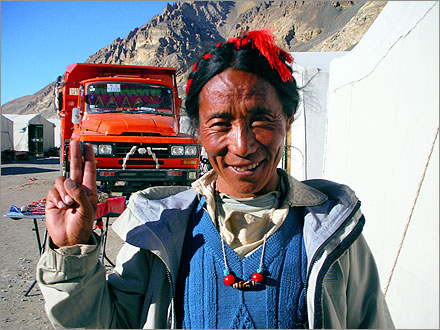

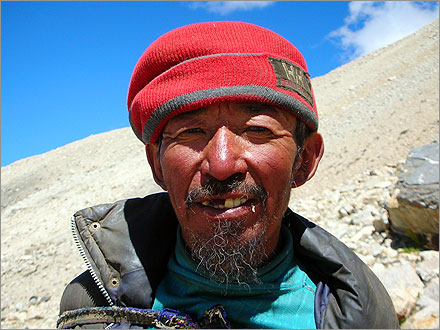

Faces of Tibet

I've finally made it back to Xinjiang. Despite having to hitch the last 7-hour leg from Miran (米兰) in a truck and arriving home at two this morning, I've already begun sorting through the hundreds of photos I snapped in Tibet. Looking at the images I've amassed, the few pictures I managed to capture of Tibetan people strike me as worth featuring here. I know it's a bit of a cliché to say that the native people you met in X country are unimagineably warm and friendy... but with Tibetans I can confirm that it's the truth. Thus, it is with great pleasure that I present to you a short photo essay, Faces of Tibet:

posted October 05, 2006 at 01:18 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (25)

October 01, 2006

Back from Everest

I'm proud to report the successful completion of my journey to Everest Base Camp (Qomolongma Base Camp, if you prefer)... and also that I've survived the mind-bendingly high altitudes (as high as 5,220m / 17,100 ft) having suffered only a small headache. Score one for the overweight and out-of-shape!

The trip from Lhasa southwest towards the crown of the Himalayas was truly impressive: crystal-clear snowmelt rivers, towering snow-capped peaks, and colorfully-clad Tibetans harvesting this year's crop of highland barley. All of you can rest assured that many more photos of the trip will be coming in the near future, but for now here's the money shot: the first rays of yesterday morning's sun striking the north face of Mount Everest.

Looks nice, eh?

In other news, I was surprised upon returning to Lhasa today at the extent to which this city has been decked out for October 1st, National Day here in the People's Republic of China. I wish I had a before-shot to contrast this photo against... the best I can do is to tell you that the red and yellow of the Chinese flag was far more conspicuous when I left this city five days ago.

Happy 57th Birthday, China!

posted October 01, 2006 at 12:36 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (38)