« November 2005 | HOME PAGE | January 2006 »

December 31, 2005

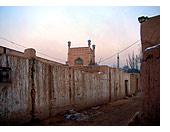

Kuqa Photos

I've finally found a few minutes to edit and upload my photos from Kuqa. They're lovely pics, if I do say so myself. Please enjoy. And as always, leave a comment... will ya? Also, an update. Chris and Rachel have been delayed for two days because of snow here in Korla, but they'll finally be coming tomorrow. Then it's off...

I've finally found a few minutes to edit and upload my photos from Kuqa. They're lovely pics, if I do say so myself. Please enjoy. And as always, leave a comment... will ya? Also, an update. Chris and Rachel have been delayed for two days because of snow here in Korla, but they'll finally be coming tomorrow. Then it's off...

posted December 31, 2005 at 04:48 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (20)

December 30, 2005

The End

UPDATE: I seem to have left out a few things. I forgot to mention that everyone else, except Lincoln, has also finished teaching for the semester. And speaking of Lincoln, he'll be travelling to Beijing soon... in order to sort out some of the details of getting married. I'm not kidding! Lincoln is marrying his Chinese girlfriend. So, congrats to him.

Well, this is it. In five minutes I'll begin my last class. And not a minute too soon... teaching is beginning to wear me down.

In other news, Chris & Rachel - who were supposed to arrive here this afternoon - are still in Beijing, as snowfall in Korla has made landing an aircraft impossible. Their plane will try again tomorrow... but until they arrive, I'll have to remain in a holding pattern. Sigh.

posted December 30, 2005 at 02:40 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (14)

December 27, 2005

Chinese Manners

I know it's a topic that's been blogged before, but it's still worth mentioning. Chinese manners are atrocious, particularly when it comes to crowds. As a teacher, I've had plenty of occasion to see my young students standing (and even marching) in perfectly orderly, straight lines. So it's something of a mystery as to why Chinese adults view lines (queues for you Brits) as a surmountable obstacle situated between themselves and whatever's at the front. I'm hard pressed to think of any single occasion over the past year when I've waited in an orderly line.

I know it's a topic that's been blogged before, but it's still worth mentioning. Chinese manners are atrocious, particularly when it comes to crowds. As a teacher, I've had plenty of occasion to see my young students standing (and even marching) in perfectly orderly, straight lines. So it's something of a mystery as to why Chinese adults view lines (queues for you Brits) as a surmountable obstacle situated between themselves and whatever's at the front. I'm hard pressed to think of any single occasion over the past year when I've waited in an orderly line.

OK, that's not true. The line at Mao's mausoleum was orderly. And I must confess to my own occasional rudenes... I used my foreign face to cut a two-hour line for train tickets last Spring Festival.

What's clear is that rudeness runs rampant throughout the People's Republic. Now, Beijing is trying to do something about it before the whole world gets offended while visiting the 2008 Olympics. The newly formed Office of the Coordinating Group for Orderly Bus-Riding is trying to bring some sort of order to one of the world's most chaotic transportation systems, bullying people into standing in line, etc. It's a good start, but I'm still waiting on the formation of a Standing Committee for the Prevention of Sidewalk-Borne Juvenile Defecation.

As always, you can read the full article below.

CHINA WATCH: Beijing Tackles Manners Ahead Of Olympics

27 December 2005

Dow Jones Commodities Service

By Andrew Batson

BEIJING, Dec 27, 2005 (DJCS via Comtex) --

City leaders promised the world a "new Beijing" when they won the right to host the 2008 Olympics. Now, four years into the capital's makeover, it seems they have decided what is really missing isn't broad avenues, lush parks or elegant hotels. It is common courtesy.

Beijing's Communist Party leadership has called for a full-blown campaign to improve etiquette and politeness ahead of the expected deluge of foreign visitors. Foul-mouthed taxi drivers have been called on to clean up their acts, and rowdy soccer fans to show more sportsmanship toward the opposing team.

"In 2008, what kind of Beijing shall we present to the globe? A Beijing both ancient and modern, a Beijing friendly and smiling," declares the Humanistic Olympics Studies Center, a city-government sponsored institute.

The next step to tackle, the powers-that-be have decided, is the art of standing in line.

Patiently waiting one's turn isn't a big feature of life in Beijing. Take an intersection on Chang'an Avenue, a main thoroughfare, on a recent Monday morning. Three lanes of cars and buses cram into a two-lane street, honking furiously. A swarm of bicyclists swerves onto the sidewalk to avoid getting trapped in the jam. Pedestrians dodge out of the way as the squeal of brakes announces a stopping bus and crowds rush to squeeze their way on.

Above them, a propaganda billboard reads: "Together enjoying a happy and harmonious life."

Trying to bring a bit more harmony to rush-hour chaos are people like Gao Shuang, a retired family-planning worker who now bears the title of deputy director of the Office of the Coordinating Group for Orderly Bus-Riding.

Gao and her colleagues have been charged with improving the 10,000 bus stops in Beijing and its suburbs, the key points in a public transportation system that serves more than 15 million people. Her office's uniformed monitors have spread out to staff 533 stops, helping make change for bus fares, assisting the elderly and handicapped, rescuing lost items - and, most importantly, getting passengers to stand in line.

Further west on Chang'an Avenue, the results of their efforts can be seen. Two monitors armed with bullhorns and red flags announce the arrival of buses, then wave waiting passengers into orderly groups. Most of the morning crowd cooperates. But the habit of queuing up isn't deeply ingrained. As one bespectacled monitor rushes over to a busy bus, he turns his back on a carefully arranged line of passengers. Without his supervision, it degenerates into a scrum as the passengers try to force their way onto another bus so packed that only the steps are free.

"Our goal is to have people line up voluntarily," says Gao. Although it is early still - the campaign started in March - she is full of confidence. "The cultural level of Beijing people is pretty high. They just need someone to remind them."

Big crowds are nothing new in China. The world's most-populous nation has long had to deal with too many people crammed into too little space, with its 1.3 billion people occupying an area slightly smaller than the continental U.S.

Yet many of the country's traditional codes of politeness, once similar to those in other Asian nations such as Japan, were shattered by the Communist revolution and its campaigns to stamp out "feudal" thinking. China's pell-mell transformation to a market economy has brought out even-ruder behavior, as people elbow others aside in pursuit of every advantage, whether in competing for school admission, jobs or business deals.

But now a growing number of Chinese feel that something important may have been left behind in today's fierce struggle to get ahead. Some Chinese have turned to religion; others are signing up for volunteer work or donating to charity. Officials hope to tap into this yearning for a greater good to overhaul bus lines.

The challenge is enormous. With only a minimal subway system, and limited, though rapidly growing, private-car ownership, Beijing's bus system is still the mainstay of transportation for many people. Beijing Public Transport Holdings Ltd., the government-owned bus company, operates 24,153 vehicles on 750 lines, carrying its riders on 4.4 billion trips a year.

Gao, who has visited New York and Washington, says those cities make her job look especially hard. "In America...it wasn't crowded at all," she says. "It didn't matter if you stood in line or not." When moving as many as 14 million passengers in one day, as Beijing's bus system can do, anything that eases the flow can make a big difference.

To make riding the bus more pleasant and convenient, the city government will be buying more and newer buses, and increasing service at peak hours. Plans also call for several new subway lines to crisscross the city and its suburbs, part of the gargantuan construction spree that is intended to bring the city's infrastructure up to Olympic standards in time for 2008.

The incessant talk of the Olympics means Beijingers increasingly feel the world's eyes upon them. And despite its simplistic sloganeering, the lining-up campaign is striking a chord with some people who feel that contemporary Chinese life has gotten a bit too rough and rude.

Qian Yuli, a diminutive woman with a ready grin, cheers on the bus-stop monitors' work at a stop along Ping'an Avenue, saying it hasn't come a moment too soon.

"It is part of the Chinese people's traditional etiquette to let the person who arrived first go ahead of you," she says. "It is just that there are some people these days that aren't so good about it."

By Andrew Batson, Dow Jones Newswires; (852) 2832 2336; andrew.batson@dowjones.com

posted December 27, 2005 at 02:43 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (25)

December 26, 2005

Stuck at Gitmo

That Uyghurs are being held in the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay is fairly well known, but this is the first time I've heard anything specific about their plight. According to Reuters, a federal judge has ruled that he cannot order the release of two Uyghurs from Gitmo, even though a military tribunal said nine months ago that the pair are not "enemy combatants". The problem? They've got nowhere to go. From the ruling:

An order requiring their release into the United States, even into some kind of parole 'bubble,' some legal-fictional status in which they would be here but would not be 'admitted,' would have national security and diplomatic implications beyond the competence or the authority of this court.

The U.S. says they won't send Abu Bakker Qassim and A'del Abdu Al-Hakim back to China because they would face persecution here. (What do you call what the U.S. has done to them?) No other countries seem interested in receiving them, so they're stuck. It's just like that crappy movie, The Terminal, except in a prison camp. Where's Spielberg?

Read the full article below.

US judge says he can't free Uighurs at Guantanamo

By JoAnne Allen

22 December 2005

(c) 2005 Reuters Limited

WASHINGTON, Dec 22 (Reuters) - A federal judge on Thursday ruled that he does not have authority to order the release of two ethnic Uighur prisoners from China detained at Guantanamo Bay, even though the U.S. military declared they are no longer "enemy combatants."

U.S. District Judge James Robertson said he finds that "a federal court has no relief to offer" Abu Bakker Qassim and A'del Abdu Al-Hakim, who are being held at the U.S. military prison in Cuba while the United States searches for a country to take them in.

"An order requiring their release into the United States, even into some kind of parole 'bubble,' some legal-fictional status in which they would be here but would not be 'admitted,' would have national security and diplomatic implications beyond the competence or the authority of this court," Robertson said in a 12-page ruling.

The two men have been detained since June 2002 at Guantanamo Bay, where the United States hold suspects in its war against terrorism launched after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. A U.S. military tribunal ruled nine months ago that the Uighurs should "no longer be classified as enemy combatants."

A lawyer working with the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights had urged Robertson to order the men released while the government continues its search for a country that will grant them asylum.

The U.S. government told the court it could not return the men to China because they would face persecution there.

Many Muslim Uighurs, who are from Xinjiang in far western China, seek greater autonomy for the region and some want independence. Beijing has waged a relentless campaign against what it calls the violent separatist activities of the Uighurs in the desert region.

Terry Henry, a U.S. Justice Department lawyer, said at an August hearing that the United States would hold the Uighurs at Guantanamo "for as long as it takes."

Henry said the two men had been transferred to a section where they were allowed more freedom of movement and more facilities than at Camp Echo, where they were previously detained.

The United States is holding about 500 foreign prisoners at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo.

posted December 26, 2005 at 04:44 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (16)

December 24, 2005

Merppy Christmukkah!

It's the most wonderful time of the year... and this year it's wonderful for Christians and Jews simultaneously. So, Merry Christmas, and Happy Hanukkah! As a special treat, I've coaxed my students into recording messages of holiday cheer for all of my friends, family and readers around the world. So, to see and hear a group of my students singing "Here Comes Santa Claus", click here. For those of you with a growing hunger for latkes, click here for "I Have a Little Dreidel". (I tried teaching "Feliz Navidad" to a bunch of my 9-year olds, but that didn't really work out. This outtake is pretty funny, though.) Don't forget to turn on your speakers!

It's the most wonderful time of the year... and this year it's wonderful for Christians and Jews simultaneously. So, Merry Christmas, and Happy Hanukkah! As a special treat, I've coaxed my students into recording messages of holiday cheer for all of my friends, family and readers around the world. So, to see and hear a group of my students singing "Here Comes Santa Claus", click here. For those of you with a growing hunger for latkes, click here for "I Have a Little Dreidel". (I tried teaching "Feliz Navidad" to a bunch of my 9-year olds, but that didn't really work out. This outtake is pretty funny, though.) Don't forget to turn on your speakers!

posted December 24, 2005 at 10:07 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (24)

December 22, 2005

Uyghur Toronto

A hot tip for all three of my Canadian readers! According to this article in the Star, a Uyghur restaurant has opened in Toronto. I can't vouch for the food, but chewing on some fatty mutton kebabs should give you Canucks a semi-decent Xinjiang experience.

This article got me wondering... where else can Uyghur restaurants be found around the world? Although I've never been, I'm aware of Cafe Kashkar (review), located in New York City's Brighton Beach. I've heard that laghman and polau can be found in Sydney, as well. There's got to be more Uyghur eateries scattered across the globe...

Uyghur food finally arrives

The Toronto Star

Dec. 14, 2005

JENNIFER BAIN

Let me introduce you to Toronto's almost invisible minority.

They are Uyghurs and they number about 150. They have one political organization and one restaurant. They also have a knack for cooking fiery lamb kebabs and homemade noodles.

You might vaguely remember when the Uyghurs (pronounced wee-gers) first captured headlines here. It was June 2004 and seven Uyghur members of a Chinese acrobatic troupe defected and claimed refugee status, saying they were fleeing political persecution and ethnic discrimination.

See, Uyghurs are Muslim Turks whose Central Asian country, East Turkistan, was annexed by China and turned into a province called the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in 1955. The oil- and gas-rich region is four times the size of California. It claims borders with Russia and Mongolia on the north, China on the east (it's outside the Great Wall), Pakistan and India on the southwest, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan and Tajikistan on the west, and Tibet on the south.

Like the Tibetans, Uyghurs want their country, culture, religion and language back. But instead of having the famous Dalai Lama as a champion, they have Rebiya Kadeer, a little-known human rights activist and former political prisoner now living in the United States.

And they have Mohamed Tohti, the Toronto-based president of the Uyghur Canadian Association. It's Tohti who invites me to the Silk Road Restaurant.

Toronto's first Uyghur restaurant is on a bland stretch of Horner Ave. east of Browns Line in an Italian area of Etobicoke. But that's okay by owner Hayrat Kurban, who opened Silk Road in September in the affordable area that he also calls home.

The space is Spartan, the menu small, the prices low, the meat halal. The menu is presented in Chinese or in photos. There's "lagman #1" and "lagman #2" — boiled handmade noodles with beef, lamb or vegetables. There are soups (lamb or chicken), shish kebabs (lamb or beef) and polos (rice platters, also called "pilows," with lamb or chicken). And there are four combo deals, for a top price of $12.59.

Tohti orders lamb shish kebabs and lagman with lamb. Kurban's teenage daughter Dildana Heyireti pours us Chinese black tea.

I fell for Uyghur food a few years ago in Beijing, where it's considered regional Chinese fare and is better known as Xinjiang food (Xinjiang means new territory/frontier). I was dubious that my cumin-spiked lamb kebabs and Afghani-style flatbreads would be thrilling, but the bewitching taste lingers. I ate in complete ignorance of Chinese-Uyghur politics.

"In Canada, we would like to make more of the public aware about Uyghurs and the problems, and we'd like to introduce our culture," allows Tohti. "Back home, we would like an opportunity for Uyghurs to decide the future peacefully. We would like to restore our independent nation."

The kebabs arrive on long, wide, silver skewers. Normally I'd use a fork to slide the meat off the skewers on to a plate, and then pop them into my mouth, but that's not the Uyghur way.

With one hand, Tohti raises the skewer parallel to his mouth, grips the kebab closest to the end with his teeth and deftly slides it off the pointed edge and into his mouth.

"You like the taste?" he asks.

I like the taste. The tender lamb has the right amount of flavour-boosting fat and is spiced with cumin seeds, red pepper flakes, salt and pepper.

"Uyghurs are Muslim — we just don't eat pork," says Tohti. "We drink, we're quite liberal, but we don't eat pork regardless. Religion has never been a slogan for Uyghurs — just a lifestyle."

Most Uyghurs follow the moderate Sufi strain of Islam. (Tohti and Kurban later shake my hand, something traditional Muslim men would never do.)

Tohti was born in Kashgar at the crossroads of the Silk Road. He got a free university education in biology — thanks to the post-Cultural Revolution times — and went to teacher's college. He was later fired for teaching English and fled to Uyghur-friendly Istanbul in 1991. While at a conference in New York City in 1998, he stepped over the border and sought asylum in Canada.

He settled in Toronto, eventually sponsoring his wife and son to join him, and buying a house in Mississauga. Tohti, a microbiologist, now does contract marketing work for energy and telecommunications companies.

But his most important work has been founding the Uyghur Canadian Association in 2000 to help refugees (83 so far) settle in. Tohti says Toronto's 150 Uyghurs live mainly in Etobicoke and North York, with pockets in Mississauga, Scarborough and downtown. Montreal has about 180 Uyghurs (and two Uyghur restaurants). Vancouver has about 50, and Calgary has eight — for a total community of less than 400.

"We are just a very invisible minority in Canada," laments Tohti, whose association marked International Human Rights Day last Saturday with a protest at the Chinese consulate in Toronto.

It's a lot to chew on. And chew we do, as our lagman arrives.

Kurban's wife makes the noodles from flour, water and salt. The dough is divided into small balls and then stretched by hand. "This is more tasteful for me than spaghetti," says Kurban, "and easier to digest."

The noodles are boiled until very soft and then served under a bed of fried vegetables (bell and hot peppers, cabbage, onion, tomatoes) and meat (in this case lamb) with a lamb soup "sauce." We mix the elements together.

"Usually English people don't like it like this — they like it fried together," observes Kurban, who ran a restaurant in the oil city of Karamay. "All English people like soft noodles that are easier to eat." (He's generalizing about English-speaking Canadians.)

Adds Tohti: "For ourselves, we make it a little harder than this and thicker than this. We prefer to eat by chewing."

Tohti speaks Uyghur, not Mandarin. He says the 10 million Uyghurs back home are now minorities because of Chinese migrants. Political to the core, he refuses to eat Chinese food, even here. "As a nation we don't go to Chinese restaurants."

At home, his family eats only "Uyghur food" — wheat, meat and vegetables. Turkish-style breakfast is tea with home-baked bread, cheese, olives, honey, raisins and almonds. Lunch is fried vegetables with rice or noodles, dumplings or kebabs. Dinner features soup, lagman and polo (rice platters).

Kurban, meanwhile, hopes to expand Silk Road's menu. He won't let his no-frills restaurant be photographed until he moves somewhere larger and decorates it with Uyghur items.

Fair enough. At least we can all try Uyghur food now, and give some thought to the Uyghur situation here and in China.

"We are much united as a community,'' says Tohti. "If there's happiness, we share. If there's sadness, we share."

And if there's food, they share.

Email the author: jbain@thestar.ca

posted December 22, 2005 at 02:43 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (40)

December 20, 2005

NY Times' Korla Journal

First came M&M's, and now the honest-to-god New York Times. Korla really has arrived! You can read Howard French's article below, which is a basic tale of Xinjiang haves vs. have-nots (with a Korla dateline). The article contains nothing that sheds any light on my year of life here on the edge of the Taklamakan, but there was one surprising tidbit:

At one club, Chinese fashion models strut and Russian dancers shimmy on a stage for ogling oil workers.

What!?! Russian dancers in Korla? Where!?! And another question... why didn't this Howard French character contact me before coming to Korla? I am, after all, the #2 Google result for "korla xinjiang". (Damn you, #1 result! Stupid old picture.) Sigh.

December 20, 2005

Korla Journal

A Remote Boomtown Where Mainly Newcomers Benefit

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

KORLA, China - The prop plane packed with businessmen swoops into this once sleepy oasis town in far western China, flying in low over the spectacular Tian Shan mountain range, now snowcapped.

At the tiny, primitive airport here, where people have to wait outdoors in the biting cold for their luggage, a billboard over the shabby terminal announces the arrival of change clearly enough: "Petroleum Hotel," it reads, in Chinese, English and the Arabic script used by the region's Uighur ethnic minority.

There are three ways to get to this city, sprouting on the edge of one of the world's largest deserts, the Taklimakan, and they all bespeak the remarkable boom under way. By night, flares from new oil fields blaze on the horizon in every direction on the bleak roads that cross the desert and run along its edge.

By day, trains disgorge passengers: newly arriving ethnic Chinese migrants from the country's crowded east or, in the harvest season, day laborers who come by the tens of thousands to pick cotton and fruit grown on spreads owned by big east coast investors.

Since this little airfield hardly befits a boomtown, a fancy new airport is being built a short distance away.

Thriving "insta-cities" are common on the prospering eastern seaboard. But in many ways what is happening in Korla and cities like it here in Xinjiang Province is even more impressive. And to a degree little suspected back east, the country's future depends on their success.

China has a bottomless thirst for oil and gas, and Xinjiang these days is producing both in ever greater quantities. Moreover, because of its proximity to Central Asia, the province has become the favorite route for pipelines bringing imported energy from Kazakhstan and beyond.

Since this is China's largest province in area, and home to the largest Muslim minority population, what happens here is crucial to the country's future stability. As with Tibet to the south, China's hold on Xinjiang is recent. Elements of the Uighur and Kazakh minorities have long yearned for independence and have sporadically engaged in terrorism.

Beijing has cracked down harshly on separatists and has banned religious schools in Xinjiang, for fear they will foment Islamic radicalism and separatism. But for now, as elsewhere in China, the government seems to be betting that strong economic growth is the best way to consolidate its control.

The province's recent record of discovering new sources of oil has certainly created an air of confidence here among government leaders and business people, most of whom hail from the east. Natural gas output has doubled in the last five years, and oil production is also rising fast, especially from the nearby Tarim Basin.

"This place is blowing and a-glowing," said Jim Scott, an ebullient Louisiana native who spends much of the year here, selling high-pressure valves and other oil field equipment to Chinese companies. "I guarantee you there's a boom on here. There's more drilling and exploring around here than you can imagine."

Beyond foreign oilmen, the explosive growth in the petroleum sector is drawing thousands of Chinese entrepreneurs from coastal cities like Shanghai and Wenzhou. Some arrive wealthy, ready to invest. Others, like, Qian Bolun, 36, who has been here for 15 years, sought their fortune in Korla when it was little more than a dusty township.

"See this," he said, nudging a glass across the lunch table at a fancy downtown restaurant owned by a Wenzhou entrepreneur. "In the old days if I bought one of these for one yuan I'd sell it here for 1.20." Nowadays Mr.Qian, who dresses in nice suits and drives a late-model Japanese sedan, deals exclusively in big-ticket items like industrial generators, tractors and mining equipment.

The new petroleum economy has left its mark all over downtown Korla, from the smart department stores and shopping malls that line the broad streets of the central city to a large nightclub district that bathes in flashing neon after sunset.

At one club, Chinese fashion models strut and Russian dancers shimmy on a stage for ogling oil workers. An entertainer with an atrocious voice belts out karaoke songs urging patrons who disapprove to "throw your money, your cellphones, whatever you've got at me."

The local Communist Party leaders speak proudly of the city's development. "In the 1990's we were a relatively backward, small and poor agricultural city, with only 100,000 residents," said Hao Jianming, deputy party secretary.

Now the city boasts 420,000 residents and is growing by 20,000 people a year. "People come here because we've become a tourism city, a recreational city with a good environment," the official said.

For all of these economic successes, Korla's problems with minorities have not been solved so much as pushed aside. On the streets of the fancy downtown, Uighur-owned shops are a rarity and Uighurs themselves are few. Across the river that divides the town into old and new, that balance is reversed.

"Uighurs usually don't have a storefront - they'll rent a place in a corner," said Hao Lin, 32, a personal computer merchant in a new computer mall. "Their main customers are Uighurs. Very few of them have business with the Tarim oil company. Those who do are Han," members as he is of China's main ethnic group.

In a barbershop that sits amid a frigid outdoor market across the river from downtown, three Uighur men sit in chairs near a coal-heated stove that warms the place.

"I studied at the university in Urumqi," the province's capital, "for three years, majoring in mechanical engineering," said the Uighur barber, Yasen Keyimu, 25, "but I can't find a job with the oil industry. Such great skills, and I can't get work."

posted December 20, 2005 at 03:59 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (17)

December 17, 2005

Off to Kuqa

I'm heading off to Kuqa (Kuche) today for a one-and-a-half day whirlwind tour of the Kizil Thousand-Buddha Caves, the Mysterious Valley, and the remains of some ancient cities. It's only about 4 hours by bus from Korla... but for those of you who want to see a map you can click here or look at this website's banner (above). Kuqa is located about 250km directly west of Korla.

posted December 17, 2005 at 08:58 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (15)

December 16, 2005

Google w/ Chinese Characteristics

The Wall Street Journal has a front-page article today about Google's efforts to increase its presence in China. The article's basic point is that after a lot of initial hemming and hawing, Google execs have dismissed any worries about the censorship efforts required to co-exist peacefully with the CCP. In fact, along with Yahoo! and other search engines, Google is already tailoring Chinese search results to comply with government restrictions.

The Wall Street Journal has a front-page article today about Google's efforts to increase its presence in China. The article's basic point is that after a lot of initial hemming and hawing, Google execs have dismissed any worries about the censorship efforts required to co-exist peacefully with the CCP. In fact, along with Yahoo! and other search engines, Google is already tailoring Chinese search results to comply with government restrictions.

For instance:

Until recently, Google's map and satellite-photo service offered Chinese Internet users something they rarely could see: a bird's-eye view of the secret compound of Zhongnanhai, where the country's top leaders live and work. But in recent weeks, close-up views from Google's satellite images of the leadership compound in Beijing have been blocked in at least parts of China.

As always, the full article can be read below. Be forewarned: it's long and mildly boring.

Limited Search: As Google Pushes Into China, It Faces Clashes With Censors --- Executives Wrestled With Issue As Others Took the Lead; Now, It's Charging Ahead --- What `Don't Be Evil' Means

By Jason Dean in Beijing and Kevin J. Delaney in San Francisco

16 December 2005

The Wall Street Journal

Google Inc. became a business superstar by relentlessly following one goal: making the world's information "universally accessible and useful." Now its ambitions overseas are bringing it up against a government whose philosophy is very different: China.

Yahoo Inc. and other rivals have been operating in China for years. Google has offered a Chinese version of its familiar search service, but it had no offices or employees in China until this year. That hindered its ability to compete for traffic and advertising among China's rapidly growing base of more than 100 million Internet users, already the world's second-largest, after that of the U.S.

Today, Google is rushing to catch up in a bid to remain competitive globally. But the move into China is giving the country's censors and security officials greater potential leverage over Google -- whose corporate mantra is "don't be evil." Beijing believes that the Internet must be firmly controlled to maintain social stability and, ultimately, the Communist Party's hold on power. It requires Internet companies operating in China to comply with the country's stringent censorship and security laws. Already, Google has been tailoring part of its service to omit sources blocked by Chinese censors. For example, when a user in China searches Google's news service, sites related to Falun Gong and other groups banned by the government don't show up.

Interviews with company executives, public statements and company documents filed as part of a continuing lawsuit show how Google finally decided to move into China after wrestling with reservations over how to reconcile Beijing's restrictions with its own principles. In the end, the opportunity in China proved too important to resist.

Google has paid a price for coming late to China. While the company's leaders debated its strategy there, Baidu.com Inc., a local rival in which Google last year bought a small stake, surged; it now ranks as China's most popular search site. That has left Google facing a rare uphill battle in the Internet search business it helped define. At a board meeting in July, Chief Executive Eric Schmidt cited "serious local competition" as a reason China topped his list of concerns, according to a court document.

"Probably we should have come earlier, but certainly better late than never," says Kai-Fu Lee, a longtime Microsoft Corp. official whose high profile in China was one of the reasons Google hired him in July to help run its new Chinese operation. Microsoft has filed a lawsuit against Google and Mr. Lee in Washington state court alleging Mr. Lee violated a noncompete agreement.

Since Mr. Lee joined Google, the company has signed up a string of local partners to sell its online ads. Mr. Lee has been setting up a research and development center in Beijing and toured 25 Chinese universities to drum up interest in working there. Google is also preparing a marketing blitz.

While other countries set some limits on what people can put on the Internet, China's constraints are perhaps the world's most extensive. It can be difficult to figure out just who enforces the rules and how. Numerous agencies -- from the National Administration for the Protection of State Secrets to the General Administration of Press and Publications -- have jurisdiction over the Internet. Foreign companies operating in China are obliged to comply with rules that block access to online content deemed politically unacceptable. Failure to heed the rules can cost a company its business licenses or trigger other penalties. Companies can also be required to turn over information on users suspected of having broken China's wide-ranging, but often vague, laws.

"We are all very aware that entering China requires us to balance two specific needs: the needs of our users and the need of operating within a political climate and a set of government regulations, as we do elsewhere in the world," says Sukhinder Singh Cassidy, Google's vice president for Asia-Pacific and Latin America operations. She says Google believes it can maintain that balance as it expands in China, saying its approach will be one that "really provides as much information and transparency as we can to users."

The balance has already proved tricky. Until recently, Google's map and satellite-photo service offered Chinese Internet users something they rarely could see: a bird's-eye view of the secret compound of Zhongnanhai, where the country's top leaders live and work.

But in recent weeks, close-up views from Google's satellite images of the leadership compound in Beijing have been blocked in at least parts of China. It's not clear how widespread the blocking is, or whether the government is behind it. Google says it didn't alter that part of its service for Chinese users. In any case, the feat betrays a high level of technical expertise.

Other big technology companies have drawn fire for accommodating the Chinese government. Cisco Systems Inc. has been criticized by free-speech advocates for selling China equipment that helps censors block Web sites. Cisco spokeswoman Penny Bruce says the company does not participate in government censorship but acknowledges standard Cisco equipment can be used to filter access to Web sites.

Human-rights activists in recent months have condemned Yahoo -- which has been in China since 1999 -- for helping Chinese police identify a Chinese journalist who allegedly used his Yahoo email account to relay to an overseas Web site the contents of a secret government order. The order related to coverage of a coming anniversary that was politically sensitive. The journalist, 37-year-old Shi Tao, is now serving a 10-year prison sentence.

Yahoo defends its actions. "We balance legal requirements against our strong belief that our active involvement in China contributes to the continued modernization of the country," it said in a statement.

Concerns about government restrictions helped Time Warner Inc. decide in 2002 to abandon a planned joint venture with Chinese computer maker Legend Holdings Ltd. for its America Online division. Time Warner Chief Executive Richard Parsons has said publicly the company balked because of concerns that Chinese regulators would be able to demand copies of subscribers' emails and other documents.

Proponents of doing business in China point out that the Internet has already facilitated an unprecedented flow of information in the country -- statements critical of the government, for example, are easy to find online.

"There is a misunderstanding in the United States about the degree to which people can access information and say what they want to say in this country," says Mr. Lee, Google's president for China.

Google began providing a Chinese-language version of its search service in 2000. Although the service soon attracted a sizable following in China, it was operated from the U.S. It wasn't until two years later that China really grabbed the company's attention.

In September 2002, Google's site was suddenly blocked in China, apparently by the government, and would-be users were directed to Chinese sites instead. The blocking took Google's executives by surprise. Co-founder Sergey Brin ordered half a dozen books on China shipped overnight to do a crash course on the country.

Google's service was finally reinstated two weeks later, for reasons that aren't entirely clear. Google says it didn't change anything about its service. But Chinese users soon found they couldn't access certain politically sensitive sites that appeared in their Google search results, suggesting that the government was censoring more aggressively.

By early 2004, Google's interest in China was building. "China is strategically important to Google," declared a January 2004 internal presentation, disclosed as part of the Microsoft lawsuit.

But company executives continued to grapple with how to establish a local operation in China without compromising their mission, according to the internal documents and people familiar with the matter. They consulted organizations, business partners and experts such as Xiao Qiang, a Chinese Internet scholar at the University of California at Berkeley. Mr. Xiao says that, despite reservations, he encouraged Google last year to set up shop in China because the Internet could help open up Chinese society.

Google had powerful reasons to eye big overseas markets like China. A majority of the searches it handles are for consumers outside the U.S. Yet Google's international advertising accounted for just 34% of its $3.2 billion in revenue last year.

Revenue flowing to search-engine companies in China is still relatively small but is growing rapidly. Research firm Shanghai iResearch Co. estimates Google had just $3.7 million in search-ad revenue in China last year, and says it ranked third in Chinese search traffic, after Baidu and the combined total for several sites run by Yahoo. Google doesn't disclose its Chinese traffic or revenue.

In June 2004, Google purchased a 2.6% stake in Baidu for $5 million. Google says it saw Baidu as an "investment opportunity." By the end of 2004, Baidu had become the most widely used search site in China, largely thanks to a marketing effort that emphasizes its local roots. Among other things, Baidu advertises that there are 38 different ways to say "I" in Chinese, saying "Chinese search is a complicated matter."

Still, Google's founders remained conflicted about China. Mr. Brin acknowledged as much in an interview published in August 2004 on the eve of Google's $1.7 billion initial public offering. The interview, with Playboy magazine, was included in Google's IPO filings. Asked about choosing between censoring search results and being blocked from China, Mr. Brin responded: "There are difficult questions, difficult challenges. Sometimes the `Don't be evil' policy leads to many discussions about what exactly is evil." He also criticized rival search engines that "have established local presences there and, as a price of doing so, offer severely restricted information."

Shortly after that, Google launched a version of its news service, which allows Chinese users to search news Web sites. In its results pages for Chinese consumers, the company excluded articles from sources the government deemed subversive -- a practice that continues today. Google argues that it would be frustrating to give people links they can't access anyway.

Mr. Xiao describes it as "a very awkward way to say, `I play by the Chinese rules.' " Google's regular searches in China do turn up links to sites that are blocked by the government.

In October 2004, Google's co-founders, Mr. Brin and Larry Page, traveled to China to talk to executives of local Internet companies. In a confidential presentation that same month, titled "China Entry Plan," Google executives outlined government censorship rules and suggested offering free advertising on Google's sites to Chinese government agencies as one possible strategy for building goodwill. The presentation, disclosed as part of the court proceedings in the Microsoft case, mentions giving users explanations when their searches are restricted. That would be a new step toward full disclosure in China, although it's unclear whether the government would allow it.

Last Dec. 23, Google executives presented another confidential "China Launch Update," which laid out strategic objectives including giving Chinese users access to the "greatest amount of information possible." The presentation, which is included in the court documents, listed a series of target dates for the company's China business, including launching a China sales-operations center by the summer of 2005. Google provided the internal China strategy documents because they are potentially relevant to Microsoft's allegations, which include that Mr. Lee's work for Google in China is directly competitive with what he did at Microsoft.

This past summer, Google executives were still fretting about having lost ground to competitors. At a July 15 board meeting, Mr. Schmidt, Google's chief executive, listed China as his top "Lowlight/Serious Concern," citing the local competition, according to an internal document disclosed as part of the Microsoft suit.

Google declined to make Mr. Brin, Mr. Page or Mr. Schmidt available for an interview for this article.

Ms. Singh Cassidy presented slides summarizing Google research that concluded that "people don't know much about us" and "over 50% [of] users who know/heard about Google can't spell Google correctly."

Whatever concerns top Google executives had about competition, by the July meeting they had apparently worked through their moral dilemma over whether to expand in China -- and decided to do so aggressively. Four days after the meeting, Google announced the hiring of Mr. Lee, with a compensation package valued at more than $10 million over four years. Born in Taiwan to mainland Chinese parents and raised partly in the U.S., Mr. Lee founded and ran Microsoft's Chinese research laboratory in the late 1990s. He enjoys nearly rock-star status among the country's technology enthusiasts.

Since his hiring, Mr. Lee has been recruiting heavily and giving speeches to large crowds of university students. Over the past several weeks, he says he has spoken to some 60,000 students. Mr. Lee says he wants to recruit leading young Chinese scientists to build a team that will be integral to Google's global R&D operations. So far, he says, Google has been able to "create instantaneous momentum" in China, he says.

Google now has offices in Beijing and Shanghai. The recruiting portion of its Chinese-language Web site currently lists more than 30 China-based positions, including a lead recruiter. Mr. Lee says he also hopes to hire five executive chefs, one for each major style of Chinese cuisine, and one to cook Western food.

Google plans a marketing blitz surrounding the launch of its Chinese ".cn" site, according to the court documents. Adding .cn would establish Google as a Chinese site and tie its brand to a domain name that is regulated by Chinese authorities. Google has also planned to introduce a new Chinese-language brand name, as Yahoo and others have done, although those plans aren't finalized, according to a person familiar with the matter.

posted December 16, 2005 at 04:17 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (39)

December 15, 2005

Ms. Kadeer Goes to Washington

Agence France Presse is running two completely different stories today on the testimony before Congress of exiled Uyghur activist Rebiya Kadeer. Kadeer (see previous post), as some of you may know, was a high-profile political prisoner in China before being released earlier this year before a visit to China by U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. Now that's she's free, Kadeer is doing her best to be a constant pain in China's ass. Anyway, the two articles:

Chinese Muslim plight highlighted in US Congress

The exiled leader of China's Muslim Uighur minority charged in the US Congress Wednesday that Beijing was using the US-led "war on terror" to persecute her people, including subjecting women to forced abortions. "Today, besides our culture, history and language, our very survival as an indigenous and unique people is now under the direct threat of Beijing's ruthless policies," said Rebiya Kadeer, who was released from nearly six years of detention in Beijing.vs.

China calls on US not to provide platform for Muslim dissident

China called on the United States Thursday not to provide a platform for the exiled leader of its Muslim Uighur minority after she used a US Congressional hearing to accuse Beijing of massive abuses.... "Everyone knows what kind of person Kadeer is. She's been engaging in criminal activities in China," Qin said.

You can read the full text of both articles below.

Chinese Muslim plight highlighted in US Congress

14 December 2005

Agence France Presse

WASHINGTON, Dec 14 (AFP) -

The exiled leader of China's Muslim Uighur minority charged in the US Congress Wednesday that Beijing was using the US-led "war on terror" to persecute her people, including subjecting women to forced abortions.

"Today, besides our culture, history and language, our very survival as an indigenous and unique people is now under the direct threat of Beijing's ruthless policies," said Rebiya Kadeer, who was released from nearly six years of detention in Beijing.

Kadeer, who was deported to the United States immediately after her release in March, alleged "massive" human rights abuses in China's predominantly Muslim Xinjiang region.

"The truth is that the Chinese government has shown it will use the war against terror as a justification to persecute Uighurs," she said.

"Attempting to stop dissent, free expression and free assembly by labelling them as terrorism is not acceptable," said Kadeer, a former millionaire businesswoman and highest-profile Uighur political prisoner who became a symbol of the struggle of her eight million community.

She claimed "tens of thousands" in Xinjiang had been held incommunicado, tortured and sentenced after unfair trials.

"Women are frequently forced to terminate their pregnancies if they are found to be pregnant outside of the Chinese family planning policies," she said.

"There are frequent reports of heavy fines and other reprisals for women who break the birth control rules," the 58-year-old Kadeer said, citing her own experience once when she had to go into hiding in the ninth month of her pregnancy after being threatened by birth control officers.

She said she had met the UN Human Rights Commission's special rapporteur on torture Manfred Nowak in Geneva before his visit to China earlier this month.

The visit was the first by a UN special rapporteur on torture and his claim of widespread torture in China had been strongly rejected by Beijing.

T. Kumar, the Washington-based Asian advocacy director of Amnesty International, told the Congressional hearing that "Xinjiang was the only place in China where political executions of Uighurs are taking place in large numbers.

"China is using the war on terror as an excuse to crack down on the Uighurs. Unfortunately they a minority and are Muslims and that fits well into Beijing agenda of branding them as terrorists," he said.

Kumar said that in the run up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Congress should ask President George W. Bush to demand a "deadline" from his Chinese counterpart Hu Jintao to stop the execution of Uighur political prisoners.

He also said Bush should invite Kadeer to the White House ahead of Hu's expected visit to Washington early next year for talks with the US leader.

"That will send a very strong message to Hu and also symbolise the plight of the Uighurs," he added.

------------------------------------------------------------------

China calls on US not to provide platform for Muslim dissident

15 December 2005

Agence France Presse

BEIJING, Dec 15 (AFP) -

China called on the United States Thursday not to provide a platform for the exiled leader of its Muslim Uighur minority after she used a US Congressional hearing to accuse Beijing of massive abuses.

Rebiya Kadeer, a former millionaire businesswoman and the highest-profile Uighur political prisoner, told the hearing that China was using the US-led "war on terror" to persecute her people with torture and forced abortions.

"The United States should not grant any platform for her to engage in activities aimed at separating China or to make these kind of remarks," foreign ministry spokesman Qin Gang told a regular briefing.

Kadeer, a native of northwest China's Xinjiang region, spent six years in detention and was deported to the United States immediately after her release in March this year.

"Everyone knows what kind of person Kadeer is. She's been engaging in criminal activities in China," Qin said. "Out of humanitarian concerns, China allowed her to go abroad to receive medical treatment."

He said Kadeer's remarks once again prove that she is closely connected with the East Turkestan movement, referring to underground groups pushing for independence for Xinjiang.

Uighur separatists, who maintain a distinct ethnic identity from the Chinese, have been fighting to re-establish an independent state of East Turkestan in Xinjiang since it became an autonomous region of China in 1955.

State media said in September separatists wishing to establish an independent East Turkestan in Xinjiang had committed 260 terrorist attacks since 1995, or roughly one every two weeks, killing 160 and injuring 440.

posted December 15, 2005 at 03:47 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (15)

Flight Details

Despite some last minute employment discussions with CCTV that might have affected my prompt return home, I've sorted things out so that I'll be flying home from China on Thursday, January 19th at 1:00 pm. For those of you who want to know, I'll be flying on Air China flight CA981, which, due to the time zone differences involved, arrives at JFK only 30 minutes after having left Beijing. (The flight is 13 hrs 30 mins long, but New York is currently 13 hours behind Beijing.) So, that means I'll be touching down in New York on Thursday, January 19th, at about 1:30 pm.

Despite some last minute employment discussions with CCTV that might have affected my prompt return home, I've sorted things out so that I'll be flying home from China on Thursday, January 19th at 1:00 pm. For those of you who want to know, I'll be flying on Air China flight CA981, which, due to the time zone differences involved, arrives at JFK only 30 minutes after having left Beijing. (The flight is 13 hrs 30 mins long, but New York is currently 13 hours behind Beijing.) So, that means I'll be touching down in New York on Thursday, January 19th, at about 1:30 pm.

posted December 15, 2005 at 11:04 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (17)

December 13, 2005

Korla: the Final Photos

As my year here in Xinjiang comes to an end, I've posted what will likely be my last set of photos from Korla. The first album includes pics from a Uyghur hatmatoi, a bonfire inside a house, and a trip to Bosten Lake (Central Asia's largest body of fresh water). As usual, random shots of my life in Korla are also featured. The second album is a selection of shots from my trip in November out to the desert to see the diversifolius poplar trees growing along the Tarim River. The trees are spectacular, and the gallery includes a few shots from my flight over the Taklamakan in an ultra-light aircraft.

As my year here in Xinjiang comes to an end, I've posted what will likely be my last set of photos from Korla. The first album includes pics from a Uyghur hatmatoi, a bonfire inside a house, and a trip to Bosten Lake (Central Asia's largest body of fresh water). As usual, random shots of my life in Korla are also featured. The second album is a selection of shots from my trip in November out to the desert to see the diversifolius poplar trees growing along the Tarim River. The trees are spectacular, and the gallery includes a few shots from my flight over the Taklamakan in an ultra-light aircraft.

P.S. The video (with sound!) from the hatmatoi, featuring Big David's awesome Uyghur dancing skills, is a bonus for all of you loyal visitors.

posted December 13, 2005 at 01:42 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (18)

Hiding in Xinjiang

Joseph Kahn writes in today's New York Times about Gao Zhisheng, defender of China's legally opressed and an all-around pain-in-the-ass as far as the Chinese authorities are concerned. The police are trying to hunt him down for his anti-authoritarian behavior... but Gao has eluded them by hiding somewhere in Xinjiang.

As links to articles in the New York Times quickly become useless, I've included the article below in it's entirety.

Legal Gadfly Bites Hard, and Beijing Slaps Him

The New York Times

By JOSEPH KAHN

BEIJING, Dec. 12 - One November morning, the Beijing Judicial Bureau convened a hearing on its decree that one of China's best-known law firms must shut down for a year because it failed to file a change of address form when it moved offices.

The same morning, Gao Zhisheng, the firm's founder and star litigator, was 1,800 miles away in Xinjiang, in the remote west. He skipped what he called the "absurd and corrupt" hearing so he could rally members of an underground Christian church to sue China's secret police.

"I can't guarantee that you will win the lawsuit - in fact you will almost certainly lose," Mr. Gao told one church member who had been detained in a raid. "But I warn you that if you are too timid to confront their barbaric behavior, you will be completely defeated."

The advice could well summarize Mr. Gao's own fateful clash with the authorities. Bold, brusque and often roused to fiery indignation, Mr. Gao, 41, is one of a handful of self-proclaimed legal "rights defenders."

He travels the country filing lawsuits over corruption, land seizures, police abuses and religious freedom. His opponent is usually the same: the ruling Communist Party.

Now, the party has told him to cease and desist. The order to suspend his firm's operating license was expanded last week to include his personal permit to practice law. The authorities threatened to confiscate it by force if Mr. Gao fails to hand it over voluntarily by Wednesday.

Secret police now watch his home and follow him wherever he goes, he says.

He has become the most prominent in a string of outspoken lawyers facing persecution. One was jailed this summer while helping clients appeal the confiscation of their oil wells. A second was driven into exile last spring after he zealously defended a third lawyer, who was convicted of leaking state secrets.

Together, they have effectively put the rule of law itself on trial, with lawyers often acting as both plaintiffs and defendants.

"People across this country are awakening to their rights and seizing on the promise of the law," Mr. Gao says. "But you cannot be a rights lawyer in this country without becoming a rights case yourself."

Ordinary citizens in fact have embraced the law as eagerly as they have welcomed another Western-inspired import, capitalism. The number of civil cases heard last year hit 4.3 million, up 30 percent in five years, and lawyers have encouraged the notion that the courts can hold anyone, even party bosses, responsible for their actions.

Chinese leaders do not discourage such ideas, entirely. They need the law to check corruption and to persuade the outside world that China is not governed by the whims of party leaders.

But the officials draw the line at any fundamental challenge to their monopoly on power.

Judges take orders from party-controlled trial committees. Lawyers operate more autonomously but often face criminal prosecution if they stir up public disorder or disclose details about legal matters that the party deems secret.

The struggle of Mr. Gao and others like him may well determine whether China's legal system evolves from its subordinate role into something grander, an independent force that can curtail abuses of power at all levels and, ultimately, protect the rights of individuals against the state.

"We have all tried to shine sunlight on the abuses in the system," says Li Heping, another Beijing-based lawyer who has accepted political cases. "Gao has his own special style. He is fearless. And he knows the law."

An Air of Authority

Mr. Gao can cite chapter and verse of China's legal code, having committed it to memory in intensive self-study. He is an army veteran and a longtime member of the Communist Party.

On a recent trip to rural Shaanxi Province, where he sneaked into a coal mine to gather evidence in a lawsuit against mine owners, he wore a crisp white shirt and tie and shiny black loafers, as if preparing for a day in court.

He is also a flagrant dissident. Tall and big-boned, he has the booming voice of a person used to commanding a room. When he holds forth, it is often on the evils of one-party rule. "Barbaric" and "reactionary" are his favorite adjectives for describing party leaders.

"Most officials in China are basically mafia bosses who use extreme barbaric methods to terrorize the people and keep them from using the law to protect their rights," Mr. Gao wrote on one essay that circulated widely on the Web this fall.

After an early career that racked up notable courtroom victories, he has plunged headlong into cases that he knows are unwinnable. He has done pro bono work for members of the Falun Gong religious sect, displaced homeowners, underground Christians, fellow lawyers and democracy activists. When the courts reject his filings, as they often do, he uses the Internet to rally public opinion.

His fevered assaults have a messianic ring. But although he became a Christian this fall and began attending services in an underground church, the motivation to pursue the most sensitive cases - and put his practice and possibly his freedom at risk - began a couple of years earlier. It was then that his idealistic beginnings as a peasant boy turned big-city lawyer gave way to simmering rage.

Mr. Gao was born in a cave. His family lived in a mud-walled home dug out of a hillside in the loess plateau in Shaanxi Province, in northwestern China. His father died at age 40. For years the boy climbed into bed at dusk because his family could not afford oil for its lamp, he recalled.

Nor could they pay for elementary school for Mr. Gao and his six siblings. But he said he listened outside the classroom window. Later, with the help of an uncle, he attended junior high and became adept enough at reading and writing to achieve what was then his dream: to join the People's Liberation Army.

Stationed at a base in Kashgar, in Xinjiang region, he received a secondary-school education and became a party member. But his fate changed even more decisively after he left the service and began working as a food vendor. One day in 1991 he browsed a newspaper used to wrap a bundle of garlic. He spotted an article that mentioned a plan by Deng Xiaoping, then China's paramount leader, to train 150,000 new lawyers and develop the legal system.

"Deng said China must be governed by law," Mr. Gao said. "I believed him."

He scraped together the funds to take a self-taught course on the law. The course mostly required a prodigious memory for titles and clauses, which he had. He passed the tests easily. Anticipating a future as a public figure, he took walks in the early morning light, pretending fields of wheat were auditoriums full of important officials. He delivered full-throated lectures to quivering stalks.

By the late 1990's, though based in remote Xinjiang, he developed a winning reputation. He represented the family of a boy who sank into a coma when a doctor mistakenly gave him an intravenous dose of ethanol. He won a $100,000 payout, then a headline-generating sum, in a case involving a boy who had lost his hearing in a botched operation.

He also won a lawsuit on behalf of a private businessman in Xinjiang. The entrepreneur had taken control of a troubled state-owned company, but a district government used force to reclaim it after the businessmen turned it into a profit-making entity. China's highest court backed the businessman and Mr. Gao.

"It felt like a golden age," he said, "when the law seemed to have real power."

That optimism did not last long. His victory in the privatization case made him a target of local leaders in Xinjiang, who warned clients and court officials to shun him, he said. He moved to Beijing in 2000 and set up a new practice with half a dozen lawyers. But he said he felt like an outsider in the capital, battling an impenetrable bureaucracy.

The Beijing Judicial Bureau, an administrative agency that has supervisory authority over law firms registered in the capital, charged high fees and often interfered in what he considered his private business.

One of his first big cases in Beijing involved a client who had his home confiscated for a building project connected with the 2008 Summer Olympics. Like many residents of inner-city courtyard homes, his client received what he considered paltry compensation to make way for developers.

When Mr. Gao attempted to file a lawsuit on his client's behalf, he was handed an internal document drafted by the central government that instructed all district courts to reject cases involving such land disputes. "It was a blatantly illegal document, but every court in Beijing blindly obeyed it," he said.

In the spring of 2003, Beijing was panicking about the spread of SARS, a sometimes fatal respiratory affliction, and Mr. Gao was fuming about forced removals. He gave an interview to a reporter for The China Economic Times arguing that SARS was much less scary than collusion between officials and developers.

"The law is designed precisely to resolve these sorts of competing interests," he said in that interview. "But their orders strip away the original logic of the law and make it a pawn of the powerful and the corrupt."

An Empty Promise

Mr. Gao is not the first lawyer to test China's commitment to the law. Even in the earliest days of market-oriented economic reforms, when the legal system was still a hollow shell, a few defense lawyers quixotically challenged the ruling party to respect international legal norms.

One such advocate is Zhang Sizhi, a dean of defense lawyers, who has accepted dozens of long-shot cases that he views as advancing the law. He defended Jiang Qing, Mao's wife, when she faced trial after the Cultural Revolution. He also represented Wei Jingsheng, perhaps China's best-known dissident.

Mr. Zhang argues that lawyers have prodded the party to develop a more impartial judiciary. But, he says, they must do so with small, carefully calibrated jolts of legal pressure.

"The system is improving incrementally," he said. "If you go too far, you will only hurt the chances of legal reform, as well as the interests of your client."

That view may reflect a consensus among seasoned legal scholars. But Mr. Gao is 37 years younger than Mr. Zhang, far less patient, and after his initial burst of idealism, deeply cynical.

If Mr. Zhang's benchmark for progress is that every criminal suspect has the right to a legal defense, Mr. Gao's became the 1989 Administrative Procedure Law, which for the first time gave Chinese citizens the right to sue state agencies. By his reckoning, it remains an empty promise.

"The leaders of China see no other purpose for the law but to protect and disguise their own power," Mr. Gao said. "As a lawyer, my goal is to turn their charade into a reality."

Following his defeat in the Beijing land dispute he plunged into the biggest land case he could find, a prolonged battle over hundreds of acres of farmland that Guangdong Province had seized to construct a university. Legally, he hit another brick wall. But he fired off scores of angry missives about the "brazen murderous schemes" of Guangdong officials. The storm of public anger he helped stir up got his clients more generous compensation.

Mr. Gao said he was told later that the party secretary of Guangdong, Zhang Dejiang, had labeled him a mingyun fenzi, a dangerous man on a mission. "He was right," Mr. Gao said.

This summer, a fellow lawyer-activist named Zhu Jiuhu was detained for "disturbing public order" while representing private investors in oil wells that were seized by the government in Shaanxi, Mr. Gao's home province.

Mr. Gao rushed to Mr. Zhu's defense with fellow lawyers, local journalists and tape recorders. He camped out in local government offices until officials agreed to meet him. He told one party boss that "he would forever be on the wrong side of the law and on the wrong side of the conscience of the people" unless he let Mr. Zhu go, according to a recording of the conversation.

After the intensive publicity campaign, Mr. Zhu was freed this fall, though under a highly restrictive bail arrangement that prevents him from practicing law.

Most provocatively, Mr. Gao has defended adherents of Falun Gong, a quasi-Buddhist religious sect that the party outlawed as a major threat to national security in 1999.

Mr. Gao has been blocked from filing lawsuits on behalf of Falun Gong members. But in open letters to the leadership, he said the secret police had tortured sect members to make them renounce Falun Gong. He described a police-run, extra-judicial "brainwashing base" where, he said, one client was first starved and then force-fed until he threw up. Another of his Falun Gong clients, he says, was raped while in police custody.

"These calamitous deeds did not begin with the two of you," he wrote in a letter addressed to President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao. "But they have continued under your political watch, and it is a crime that you have not stopped them."

The Police Circle

The crackdown came first as a courtesy call.

Two men wearing suit jackets and ties, having set up an appointment, visited his office. They identified themselves as agents of State Security, the internal secret police, but mostly made small talk until one of them mentioned the open letter Mr. Gao had written on Falun Gong.

"They suggested that Falun Gong was more of a political issue than a legal issue and maybe it was best left to the politicians," Mr. Gao recalled. "They were very polite."

When they prepared to leave, however, one of them said, "You must be proud of what you have achieved as a lawyer after your self-study. Certainly you must be worried should something happen to derail that."

Mr. Gao said he talked to his wife and considered the future of his two children. He wondered whether he could still afford his Beijing apartment and his car if his business collapsed.

"Anyone who says he does not consider this kind of pressure is lying," Mr. Gao said. "But I also felt more than ever that I was putting pressure on this reactionary system. I did not want to give that up."

His resistance hardened. The Beijing Judicial Bureau handed him a list of cases and clients that were off limits, including Falun Gong, the Shaanxi oil case and a recent incident of political unrest in Taishi, a village in Guangdong. He refused to drop any of them, arguing that the bureau had no legal authority to dictate what cases he accepts or rejects.

This fall, he said, security agents have followed him constantly. He said his apartment courtyard has become a "plainclothes policeman's club," with up to 20 officers stationed outside. He and his wife bring them hot water on cold nights.

On Nov. 4, shortly after being warned to retract a second open letter about his Falun Gong cases, Mr. Gao received a new summons from the judicial bureau.

This time, the bureau provided a written notice that said it had conducted routine inspections of 58 law firms in Beijing. Mr. Gao's, it was discovered, had moved offices and failed to promptly register the new address, which it called a serious violation of the Law on Managing the Registration of Law Firms. He was ordered to suspend operations for a year.

When the requisite public hearing was held, Mr. Gao sent two lawyers to represent him. But he boarded a plane for Xinjiang, where he had a medical case pending and where he wanted to inquire about abuses against members of an underground Christian church.

The edict was not only not overturned after the hearing, it was broadened. By late November, the bureau issued a new notice demanding that Mr. Gao hand over his personal law license as well as his firm's operating permit. Both had to be in the hands of the bureau by Dec. 14. The authority would otherwise "use force according to law to carry it out."

When he received that second order, Mr. Gao had escaped his police tail and traveled to a location in northern China that he asked to keep secret. He was conducting a new investigation into torture of Falun Gong adherents. A steady stream of sect members visited him in the ramshackle apartment he is using as a safe house. He tries to meet at least four each day, taking their stories down long hand.

"I'm not sure how much time I have left to conduct my work," Mr. Gao said. "But I will use every minute to expose the barbaric tactics of our leadership."

posted December 13, 2005 at 11:10 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (22)

December 12, 2005

Outsourced Gamers

I meant to blog this a few days ago. The New York Times had an article on Friday about the latest "outsourcing-to-China" craze... that is, gamers. Yes, that's right. You can pay a nerd in China - who's time is far less valuable than your own - to play an online game using your account for days on end, thereby advancing you to later and more exciting levels. Some Chinese companies have even caught on and started paying Chinese gamers to put together powerful avatars for sale online.

I meant to blog this a few days ago. The New York Times had an article on Friday about the latest "outsourcing-to-China" craze... that is, gamers. Yes, that's right. You can pay a nerd in China - who's time is far less valuable than your own - to play an online game using your account for days on end, thereby advancing you to later and more exciting levels. Some Chinese companies have even caught on and started paying Chinese gamers to put together powerful avatars for sale online.

Can I hope that someday soon I'll be able to pay a Chinese guy to wait online for me at the Department of Motor Vehicles? In any case, you can read the full article below.

Ogre to Slay? Outsource It to Chinese

The New York Times

December 9, 2005

By DAVID BARBOZA

FUZHOU, China - One of China's newest factories operates here in the basement of an old warehouse. Posters of World of Warcraft and Magic Land hang above a corps of young people glued to their computer screens, pounding away at their keyboards in the latest hustle for money.

The people working at this clandestine locale are "gold farmers." Every day, in 12-hour shifts, they "play" computer games by killing onscreen monsters and winning battles, harvesting artificial gold coins and other virtual goods as rewards that, as it turns out, can be transformed into real cash.

That is because, from Seoul to San Francisco, affluent online gamers who lack the time and patience to work their way up to the higher levels of gamedom are willing to pay the young Chinese here to play the early rounds for them.

"For 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, my colleagues and I are killing monsters," said a 23-year-old gamer who works here in this makeshift factory and goes by the online code name Wandering. "I make about $250 a month, which is pretty good compared with the other jobs I've had. And I can play games all day."

He and his comrades have created yet another new business out of cheap Chinese labor. They are tapping into the fast-growing world of "massively multiplayer online games," which involve role playing and often revolve around fantasy or warfare in medieval kingdoms or distant galaxies.

With more than 100 million people worldwide logging on every month to play interactive computer games, game companies are already generating revenues of $3.6 billion a year from subscriptions, according to DFC Intelligence, which tracks the computer gaming market.

For the Chinese in game-playing factories like these, though, it is not all fun and games. These workers have strict quotas and are supervised by bosses who equip them with computers, software and Internet connections to thrash online trolls, gnomes and ogres.

As they grind through the games, they accumulate virtual currency that is valuable to game players around the world. The games allow players to trade currency to other players, who can then use it to buy better armor, amulets, magic spells and other accoutrements to climb to higher levels or create more powerful characters.

The Internet is now filled with classified advertisements from small companies - many of them here in China - auctioning for real money their powerful figures, called avatars. These ventures join individual gamers who started marketing such virtual weapons and wares a few years ago to help support their hobby.

"I'm selling an account with a level-60 Shaman," says one ad from a player code-named Silver Fire, who uses QQ, the popular Chinese instant messaging service here in China. "If you want to know more details, let's chat on QQ."

This virtual economy is blurring the line between fantasy and reality. A few years ago, online subscribers started competing with other players from around the world. And before long, many casual gamers started asking other people to baby-sit for their accounts, or play while they were away.

That has spawned the creation of hundreds - perhaps thousands - of online gaming factories here in China. By some estimates, there are well over 100,000 young people working in China as full-time gamers, toiling away in dark Internet cafes, abandoned warehouses, small offices and private homes.

Most of the players here actually make less than a quarter an hour, but they often get room, board and free computer game play in these "virtual sweatshops."

"It's unimaginable how big this is," says Chen Yu, 27, who employs 20 full-time gamers here in Fuzhou. "They say that in some of these popular games, 40 or 50 percent of the players are actually Chinese farmers."

For many online gamers, the point is no longer simply to play. Instead they hunt for the fanciest sword or the most potent charm, or seek a shortcut to the thrill of sparring at the highest level. And all of that is available - for a price.

"What we're seeing here is the emergence of virtual currencies and virtual economies," says Peter Ludlow, a longtime gamer and a professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. "People are making real money here, so these games are becoming like real economies."

The Chinese government estimates that there are 24 million online gamers in China, meaning that nearly one in four Internet users here play online games.

And many online gaming factories have come to resemble the thousands of textile mills and toy factories that have moved here from Taiwan, Hong Kong and other parts of the world to take advantage of China's vast pool of cheap labor.

"They're exploiting the wage difference between the U.S. and China for unskilled labor," says Edward Castronova, a professor of telecommunications at Indiana University and the author of "Synthetic Worlds," a study of the economy of online games. "The cost of someone's time is much bigger in America than in China."

But gold farming is controversial. Many hard-core gamers say the factories are distorting the games. What is more, the big gaming companies say the factories are violating the terms of use of the games, which forbid players to sell their virtual goods for real money. They have vowed to crack down on those suspected of being small businesses rather than individual gamers.