« January 2007 | HOME PAGE | March 2007 »

February 28, 2007

Sandstorm of Death

Every time I leave Xinjiang, deadly sandstorms seem to plague the region. The message from the man upstairs to residents of Xinjiang? You'd better keep ol' Michael around, if you know what's best for you! Alright, alright... I shouldn't be treating death and destruction so lightly. But sandstorms in February? Something freaky is going on.

The jist of the story:

The Urumqi Railway Bureau says three people have been confirmed dead and 34 were injured, two of them are in a serious condition.

According to the Urumqi Railway Bureau, 11 carriages of Train No. 5806 were derailed by winds gusting to 144km at around 2:00 a.m, soon after it left Turpan, about 120 km from Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang. The train was on its way to Aksu, in southern Xinjiang.

"Winds measured force 13, as powerful as a hurricane," said the railway bureau.

"Sand and dust cracked the window panes soon after the train left Turpan, and blew some of the cars off the tracks as we were trying to plug up the windows," said passenger Su Chuanyi, a local TV journalist.

Not exactly the kind of story that makes me long anytime soon for the warm, sandy, deadly embrace of Xinjiang. Have I mentioned that it's a lovely, sunny, and clear day here in New Jersey?

You can read the whole Xinhua wrap-up below.

China Exclusive: Strong winds derail train, leaving more than 30 casualties in NW China

28 February 2007

Xinhua News Agency

By Xinhua writer Ji Shaoting

URUMQI, Feb. 28 (Xinhua) -- At least three passengers have been killed and more than 30 injured after the train they were traveling in was derailed by hurricane force winds, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region early Wednesday, rescuers said.

The Urumqi Railway Bureau says three people have been confirmed dead and 34 were injured, two of them are in a serious condition.

According to the Urumqi Railway Bureau, 11 carriages of Train No. 5806 were derailed by winds gusting to 144km at around 2:00 a.m, soon after it left Turpan, about 120 km from Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang. The train was on its way to Aksu, in southern Xinjiang.

"Winds measured force 13, as powerful as a hurricane," said the railway bureau.

"Sand and dust cracked the window panes soon after the train left Turpan, and blew some of the cars off the tracks as we were trying to plug up the windows," said passenger Su Chuanyi, a local TV journalist.

"The first rescue team of more than 100 people, including doctors and police officers, arrived at 4:30 a.m," Su said.

Later almost a thousand rescuers were at the scene, said local railway bureau.

"The tragedy happened when most passengers were asleep. I fell off from the middle bunk bed when I was just going to get up and plug the cracked windows," said a 34-year-old passenger named Li Zhi from a local travel agency.

"I blacked out for quite a while and woke up when other passengers were asking how I was," said Li who was in the fourth car of the train, which he said rolled three times down an embankment.

Li saw a trapped man whose body was half way out a window.

"I tried to pull him out but I couldn't. The only thing I can do for him is to cover his body with a sheet," the still shaken Li told Xinhua.

"We tried to calm down and plan out own rescue," Li said. A few of strong young man broke the windows, and helped the old and young get out first. One by one all the passengers got out, Li said.

"I got out in my bare feet without even a penny in my pocket," Li said.

The temperature was minus 10 Celsius.

Li was taken 70 km to a hospital. "I can't move my waist and I feel dizzy when I lower my head," Li said.

The area is well known for strong winds and is near a wind farm. A similar accident derailed 11 train carriages of a train in 2001.

The railway, which was blocked for 11 hours, is now back in operation and 1,100 passengers of the derailed train have reached their destination, said the local railway bureau.

Wednesday is the tenth day Chinese lunar new year and many of the passengers were returning home after visiting family members and friends over the holiday. The Urumqi Railway Bureau earlier predicted it would handle 1.397 million local passengers during Spring Festival.

One train with more than thousand passengers, most of them were university students heading back to school was cancelled, said the local railway bureau.

Winds were so heavy rescuers has to wait for them to subside.

"The wind was too strong to stand against. My face and hands were scratched by the sand and small stones. Sand filled my mouth whenever I took a breath," said a local rescuer named Zhang Xiaoli.

"While it's always winds in this area, it's rare to see a train derailed by wind," Zhang said.

Wind, cold and snow hit Xinjiang two days ago, said the regional meteorological station.

A task force from the Ministry of Railways is heading for the scene.

In April last year the windows of a train from Urumpi to Beijing were cracked by a sand storm and the train was delayed 32 hours near where Wednesday's accident occurred.

Eleven train cars were derailed by strong winds in April 2001 in the same section. No one was killed in that accident.

The rail line is a branch of Lanzhou-Xinjiang Railway.

In 2003, the Ministry of Railways and Urumqi Railway Bureau built a three-meter-tall wall along the main rail line to protect trains from strong winds. The project cost 1.3 billion yuan (about 168 million U.S. dollars). Xinhua reporter Zhao Chunhui and Ding Xiuling based in Xinjiang Autonomous Region contributed to the story.

posted February 28, 2007 at 10:14 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (54)

February 26, 2007

High Noon in Xinjiang

Who knew that German weekly Der Spiegel had an international edition written in English? Well, consider yourself informed. I came across the site upon discovering an article published this week about increased ethnic tension brewing in Xinjiang. They recycle a lot of the same old remarks about Xinjiang, but there are some good bits.

The best part is that the article throws more fuel on the Xinjiang 2021 fire I started a couple months back. Remember that raid on a Uyghur terrorist training camp near Kashgar in January? Well,

Since then military transport aircraft and helicopters have been making regular landings at the Kashgar airport, as China builds up its forces in its mountainous border regions. Neighboring Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan are seen as the principal hideouts for the region's Islamists.

Since the battle at the ETIM camp, anyone in Kashgar who is unable to show identification is considered a suspect. The police search vehicles on arterial roads and security forces, uniformed or in civilian clothing, lurk in the city. "We stay home at night," says Mohammed, a 26-year-old Uighur who operates a clothing stand near the "Street of the Liberation." The police keep a watchful eye on Kashgar's crowds, even at events as seemingly harmless as the opening of a new supermarket across the street from the mosque.

So, when the shit goes down, I don't wanna hear anybody saying that I didn't tell you beforehand! Again, consider yourself informed.

There is one Xinjiang stereotype propagated towards the end of the article that I believe to be untrue, at least in the modern age:

Fighting, though, isn't the only reason the soldiers are there. Many have also been sent to the region to develop their own farms and factories. According to one soldier, whenever they encounter unrest the troops simply change into the uniforms of the armed People's Police.

Is this really still going on? Somehow I doubt it. I mean, I've heard the ol' "hoe in one hand, gun in the other" slogan from the early days of the bingtuan. I've even seen a statue in Korla depicting those dual roles literally. But if the folks I see out on the army farm cutting tomatoes are indicative of the situation, these days the farming is left to the farmers and the soldiering is left to the soldiers. Anyone out there have information to the contrary?

You can read the entire Der Spiegel article below.

GUNS AND STEEL ON THE SILK ROAD: High Noon in China's Far West

SPIEGEL ONLINE - February 22, 2007, 04:34 PM

URL: http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/0,1518,467931,00.html

By Wieland Wagner

China is sending more troops to the mostly Muslim province of Xinjiang in the far west of the country. Concerns are rising in Beijing of ethnic unrest in the border region. Its plans for economic development there may be in trouble.

Mao Tse Tung defies the icy wind blowing from the Pamir Mountains across the city of Kashgar. Beijing is worlds away from this spot on the historic Silk Road, not far from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Which is perhaps why the Chairman Mao needs such a tall base for his statue, perched 24 meters (79 feet) above the "Square of the People." But Mao is strikingly alone -- the square is practically devoid of people.

It is time for prayer. A few blocks away, locals are streaming into the Id-Kah Mosque, the largest Muslim house of worship in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region, home to the Uighur minority in northwestern China.

The faithful wear their fur turbans pulled down over their faces. It's bitterly cold, but it is also to disguise their identities. Many are afraid of being recognized.

Muslims are the majority in Kashgar, giving this ancient city bordering the Tarim Basin the air of an Arabian oasis. Uighurs, Kyrgyz and Tajiks bring their dates, nuts and pomegranates to the market on donkey carts. Instead of Peking Duck, the air smells of roast lamb and flatbread.

Veil of suspicion

But a veil of suspicion hangs over the region. Unlike in other parts of Central Asia, the muezzin in Kashgar is not permitted to use a loudspeaker to call the faithful to prayer from the minaret. His voice sounds muffled as it emerges from the interior of the mosque. Civil servants are essentially barred from taking part in Muslim prayers, evidence of fears among China's atheist leadership that Islam could develop into the core of an independence movement.

Xinjiang in north-western China is home to a large Muslim population.

In January Chinese police attacked a base used by fighters of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) in western Xinjiang. The organization supposedly has ties to the al-Qaida terrorist network. It was the bloodiest battle between Chinese government forces and Uighur resistance fighters in a decade. A Chinese police officer was killed, and Beijing has since celebrated the man as a martyr of the revolution. The police shot and killed 18 of the alleged terrorists and arrested 17 suspects.

Since then military transport aircraft and helicopters have been making regular landings at the Kashgar airport, as China builds up its forces in its mountainous border regions. Neighboring Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan are seen as the principal hideouts for the region's Islamists.

Since the battle at the ETIM camp, anyone in Kashgar who is unable to show identification is considered a suspect. The police search vehicles on arterial roads and security forces, uniformed or in civilian clothing, lurk in the city. "We stay home at night," says Mohammed, a 26-year-old Uighur who operates a clothing stand near the "Street of the Liberation." The police keep a watchful eye on Kashgar's crowds, even at events as seemingly harmless as the opening of a new supermarket across the street from the mosque.

Massacre in the mountains

In some ways the heightened surveillance runs counter to the Chinese government's aims in the region, where it welcomes every new business, factory or apartment building -- any building to displace the city's traditional earthen structures. Beijing is spending billions of Yuan to develop a modern-day Silk Road in this border region, complete with new pipelines, railroad lines and roads. China plans to use the new infrastructure to bring oil and natural gas from Central Asia to the Chinese heartland and export its electronics and textiles in the other direction.

Beijing's strategists are pinning their hopes on new wealth to pacify the troubled Xinjiang region. But the recent massacre in the mountains could scare away investors, as China wages its own war on Islamist terrorists.

Chinese President Hu Jintao has long believed that his country is already a "victim of terrorism." He is referring primarily, though, to forces fighting for regional independence, or at least for greater autonomy from the central government far to the east.

The government has charged Uighur dissident Rebiya Kadeer with "violent terrorist activities." Two years ago Beijing forced the prominent local businesswoman to emigrate to the United States and imposed prison sentences on her sons in Xinjiang for alleged tax evasion. In quoting an angry Internet user who called Kadeer a "separatist monster," the official China Daily expressed one of Beijing's greatest fears: that the dissident, who was elected president of the World Uighur Congress last year, could be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The "war on terror" doubles as a convenient fig leaf for the Chinese leadership. In 2001 Beijing used its concerns over alleged terrorist activities as the impetus to establish the Shanghai Organization for Cooperation, which also counts Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan as members. The dangers of terrorism were also used to justify joint military exercises with the Russians in 2005. Three years earlier China gained US support for its campaign to have the United Nations classify the Islam independence movement ETIM as a terrorist organization. But little in fact is known about ETIM's goals, and Beijing has yet to produce clear evidence of the organization's alleged ties to al-Qaida.

"Robbing us of our livelihood"

Despite its successes, the Chinese leadership remains seriously concerned, fearing a reprise of the bloody unrest of recent decades in Xinjiang. According to official figures, the resistance movement's activities cost 162 lives and caused 400 injuries between 1990 and 2001. Out of an apparent fear of attacks, China imposed restrictions on passengers carrying liquids onto airplanes as far back as 2003 -- well before similar rules were enacted in Europe and the United States. With a view toward the 2008 Olympic Games, security has already been tightened in and around the capital.

China's strategy of using the blessings of capitalism as one of its tools in fighting terrorism tends to have the opposite effect among Uighurs. More and more ethnic Chinese are immigrating into Xinjiang; their share of the population has grown to at least 40 percent since 1949.

The change in the region's ethnic makeup has widened the gap between rich and poor, and social decline tends to affect Uighurs like textile vendor Mohammed first. "The Chinese are the ones running businesses here today," he says angrily. "They are robbing us of our livelihood."

In addition, with Xinjiang having evolved into a virtual military base, even the most peaceful of Uighurs are deterred from staging demonstrations. Tens of thousands of Chinese troops, for example, are stationed in Shule, a garrison town near Kashgar.

Fighting, though, isn't the only reason the soldiers are there. Many have also been sent to the region to develop their own farms and factories. According to one soldier, whenever they encounter unrest the troops simply change into the uniforms of the armed People's Police.

As if that weren't enough, the Chinese government also controls the clocks in Xinjiang. Although the capital is almost 3,000 kilometers (1,865 miles) away, Xinjiang runs on Beijing time.

Despite the official mandate, clocks at the mosque in Kashgar are set, in quiet protest, to the real local time, which is two hours earlier than Beijing time -- exactly the way nature would have it in Xinjiang.

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan

posted February 26, 2007 at 03:18 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (46)

February 25, 2007

Laughter is the Best Medicine

Oh, man. How I love a good ol' fashioned anecdote! They've got all the best parts of a story (protagonist, plot, conflict, etc.) but with a healthy dose of humor thrown in to show us what a crazy, crazy world we live in.

Oh, man. How I love a good ol' fashioned anecdote! They've got all the best parts of a story (protagonist, plot, conflict, etc.) but with a healthy dose of humor thrown in to show us what a crazy, crazy world we live in.

Anecdotes make life worth living, no?

So it was with great pleasure earlier this week that I found an amusing reminiscence of an experience at Kasghar airport hidden away in the Travel section of the New York Times. An excerpt:

Reluctantly, I stepped into the slot where bags are passed though the counter. No objection from the agent. I walked over to the conveyor belt. Still no protests. I climbed on to the carousel. The agent smiled and flipped a switch. The belt lurched forward.

I passed through the slit rubber curtain into a dark, cavernous space.

You can read the whole anecdote below.

You've gotta love the intersection of pointless Chinese bureaucracy and Xinjiang tourism. Where else on Earth could the problem of bringing knives onto an airplane be solved simply by skipping the security check altogether?

On a lesser scale, I've more than once had a similar experience boarding long-distance buses in northwest China. The ticket lady will tell me that I've got to get some sort of travel permit from the Public Security Bureau (yeah, I'm thinking of you Golmud)... undoubtedly a huge pain-in-the-ass. Of course, I'm also told that I can circumvent this inconvenience simply by waiting for the bus to pick me up outside the station gates, rather than boarding with everyone else. Problem. Solved.

How quaintly bureaucratic yet lacking any semblance of logic!

A Round Trip on a Conveyor Belt in China

By RON ROBINS, as told to Christopher Elliott.

February 20, 2007

Frequent Flier

The New York Times

In North American airports, there are warnings posted above the luggage carousels: “Please don’t step on the conveyor belt.” These signs are often missing when you travel internationally, and I recently discovered why.

Two years ago, I was in China with a friend who is a professor at the University of Texas medical school, and a group of his students. We had traveled from the old capital of Xian, westward through the oasis towns and deserts of central China, ending up in the 2,000-year-old Uighur city of Kashgar, near the Afghanistan border.

At a sprawling bazaar known locally as the Camel Market, I picked up several small handmade Uighur knives as gifts. Instead of packing them into my checked-in luggage, I slipped them into my carry-on bag by mistake.

We flew out of Kashgar the next day from an incongruously modern airport recently built to open up this very remote part of China to trade and tourism. Everything went fine until my carry-on bag passed through the X-ray machine.

A security screener opened my bag and removed the knives. Although he spoke no English, it was clear they were not allowed on the plane.

But instead of tossing my mementos in the trash, he handed them to me and pointed in the direction I had come, back toward the ticket counter. Interpreting this as a suggestion that I might be able to check the knives through, I returned to the ticket counter.

The ticket agent also spoke no English, but nodded knowingly as I held up the knives. Speaking in Uighur, he pointed to the empty luggage conveyor belt.

“Well,” I thought, “he’s trying to tell me that my bag has already gone and there’s nothing he can do.” I thanked him and turned to leave.

But he stopped me with a tap on the shoulder and again pointed to the conveyor belt. This time he made a more sweeping gesture from me to the conveyor belt.

Reluctantly, I stepped into the slot where bags are passed though the counter. No objection from the agent.

I walked over to the conveyor belt. Still no protests.

I climbed on to the carousel. The agent smiled and flipped a switch. The belt lurched forward.

I passed through the slit rubber curtain into a dark, cavernous space. My moving sidewalk looped and rumbled through the bowels of the airport. After a while, a faint light appeared, leading through another slit curtain that spilled into a baggage loading area.

The baggage handlers were not at all surprised to see a knife-wielding American emerge from the conveyor belt. They helped me find my bag and I repacked my knives.

Now the only question was: How do I get back to the terminal? No one spoke English, so there was no point asking for directions. Gestures didn’t do much good either.

Seeing no other way out, I turned around, pushed through the slit curtain, double-timed it back up the belt and burst through the top curtain into the check-in area.

The ticket agent was clearly expecting me, since other bags were stacked on the floor in front of the belt awaiting my return.

I bowed to him in thanks, not only for saving my Uighur knife collection, but also for surviving my behind-the-scenes tour of a Chinese airport.

By Ron Robins, as told to Christopher Elliott. E-mail: elliott@nytimes.com

posted February 25, 2007 at 01:54 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (27)

February 24, 2007

Caption Contest #3

Welcome to a very special Spring Festival edition of the monthly caption contest! Perhaps you can find something humorous, ironic, or otherwise abnormal to say about the following photograph:

Seeing as I'm relaxing back in the States and feeling a bit lazy, I'm gonna give you nine whole days to submit your entries for the third contest. You've got until 23:59:59 Beijing time on Sunday, March 4th... not a moment to waste.

Also, some of you may remember that I've decided to ask Meg - who blogs over at Violet Eclipse - to decide the winner this time. She's a Jersey girl who somehow managed to win the first two caption contests... so, it's time to let someone else to have a chance.

Good luck, my funny friends!

posted February 24, 2007 at 12:01 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (28)

February 23, 2007

Who is Huseyin Celil?

Who is Huseyin Celil? That's the question addressed in a recent article in Canadian newspaper The Globe & Mail. The Chinese answer is simple: Celil is a Uyghur terrorist bent on splitting the motherland, rightly imprisoned in Urumqi where he awaits possible execution. If you're Canadian, however, things are a bit more complex. That's because Celil is a Canadian citizen, one with protected refugee status from the UNHCR and a young family back in Burlington, Ontario. So, will the real Huseyin Celil please stand up?

Who is Huseyin Celil? That's the question addressed in a recent article in Canadian newspaper The Globe & Mail. The Chinese answer is simple: Celil is a Uyghur terrorist bent on splitting the motherland, rightly imprisoned in Urumqi where he awaits possible execution. If you're Canadian, however, things are a bit more complex. That's because Celil is a Canadian citizen, one with protected refugee status from the UNHCR and a young family back in Burlington, Ontario. So, will the real Huseyin Celil please stand up?

Things started out innocently enough for the young man from Kashgar, with a bit of mild defiance:

The young imam was accused of using a megaphone to amplify the call to prayers at his mosque, standard practice in most Muslim countries. In China, it landed him in prison. The 25-year-old religious leader was jailed for 48 days, according to his family, the beginning of a cat-and-mouse game that would stretch over 13 years, two continents, and at least six countries.

But it's after Celil first attracted the attention of the Chinese authorities that the facts start to get blurry. Did Celil travel on a fake passport using the name Guler Dilaver? Did Guler Dilaver assassinate the "head of Uighur society in Kyrgyz Republic" in March 2000? Did this same person commit an act of terrorism against a delegation from Xinjiang on May 25, 2000? Is Celil a real international criminal or is that only according to the "Interpol National Central Bureau in Uzbekistan"?

Only one thing is clear after reading the article: Huseyin Celil is neither a clear-cut Uyghur terrorist nor a typical maple syrup-lovin' Canadian.

You can read the full profile below.

Who is Huseyin Celil?

Caught in the grip of Beijing; He is a very stubborn man, a pious imam and a proud Uighur. He's drawn the wrath of China's authorities who brand him a terrorist. Huseyin Celil is also a Canadian, jailed in an unknown prison in western China. And his case is straining relations between the two nations

by GEOFFREY YORK and OMAR EL AKKAD

The Globe and Mail

17 February 2007

URUMQI, CHINA and BURLINGTON, ONT. -- The Chinese justice system took its first crack at Huseyin Celil on a late summer day in 1994.

In most countries, his offence would not have provoked an arrest and a jail term. The young imam was accused of using a megaphone to amplify the call to prayers at his mosque, standard practice in most Muslim countries. In China, it landed him in prison.

The 25-year-old religious leader was jailed for 48 days, according to his family, the beginning of a cat-and-mouse game that would stretch over 13 years, two continents, and at least six countries. Even in the years he spent outside the country, China's interest in Mr. Celil never seemed to wane; it even led to regular searches of his relatives' homes long after he was gone.

Mr. Celil believed he had finally reached safety when he won protection from UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, and then entered Canada in 2001.

But that refuge proved temporary. Today Mr. Celil languishes in an unknown prison in the far west of China, facing a heavy sentence or possible execution on terrorism allegations. His case has triggered a crisis in Canadian-Chinese relations.

A close look at Mr. Celil's life story, based on interviews and research by The Globe and Mail over the past several months in Canada and China, reveals a portrait of an intensely stubborn man who defied the will of the Chinese authorities for most of his life.

In China's eyes, Mr. Celil is not just a religious man from a farming community, he is a citizen accused of terrorism, and the definition of terrorism extends well beyond the realm of violence. Human-rights groups argue that peaceful protest or rebellion easily fall under the scope of what China considers a crime.

In the official Chinese view of the Celil case, Canada matters little.

“Of course, as a courtesy, we will brief your embassy officials [about what happens to Mr. Celil],” He Yafei, China's assistant minister of foreign affairs for North America, said this month, “but as a matter of courtesy, not as a matter of obligation.”

China has so far produced no details to support the charges against Mr. Celil. Senior Canadian officials have repeatedly tried to gain access to the imprisoned Canadian, but China refuses to budge. It is on this point that Ottawa and Beijing have had trouble seeing eye-to-eye. Canadian officials have not questioned China's right to level charges against Mr. Celil, but they do object to being prohibited from seeing him.

All the Canadian government knows is that Mr. Celil is charged in connection with terrorist acts.

“I have never seen any documentation of direct evidence whatsoever to link Mr. Celil [to these acts],” Foreign Affairs Minister Peter MacKay said in an interview yesterday. In his strongest criticism yet of Beijing's handling of the Celil case, Mr. MacKay said Chinese authorities have shown “complete indifference to our desire, and more importantly [Mr. Celil's family's] desire to know about his well-being.”

China regularly denies travel documentation to anyone seen as defying the party line on national unity. As such, Mr. Celil has never been allowed to carry a Chinese passport, his family and lawyers say. They add that he actively tried to renounce his Chinese citizenship upon his arrival in Canada, but China has no mechanism for people to do so.

China maintains a tight grip on Xinjiang, the predominantly Muslim region on the western fringes of the country. By refusing to kowtow to Chinese limits on religion, Mr. Celil doomed himself to a lifetime of conflict with state police and security agents.

Mr. Celil was born on March 1, 1969, on a small farm about 70 kilometres from Kashgar, a Muslim city in Xinjiang. He was the second-youngest of nine children. His impoverished parents grew cotton and wheat on a single hectare of farmland, earning an annual income of barely $250 (U.S.).

He and his family were members of the Uighur ethnic people — the traditional majority in Xinjiang. The Uighurs, like the Tibetans, were resentful of Chinese dominance of their homeland. Like the Tibetans, they have been subjected to decades of repression by Chinese authorities who feared an independence movement.

Uighur activists have fought for greater autonomy from China, many of them seeking to regain the independence that the region briefly claimed in the 1930s and the 1940s after Muslim rebellions against Chinese rule. By the late 1980s, the conflict would erupt into sporadic violence, and China responded with a harsh crackdown.

At the age of 13, Mr. Celil graduated from primary school. But, unlike his eight siblings who stayed on the farm, Mr. Celil decided to continue his education by going to mosques to study the Koran. After three years at rural mosques, he moved to Kashgar to continue his religious studies for another two years.

It was an unusual move for a farm boy, revealing the defiant nature that continued throughout his life. He became the first in his family to study the Koran. “We were very proud of him,” said his older brother, Sarmeti Celil.

By the early 1990s, still in his early 20s, Mr. Celil was an imam at a small mosque in Kashgar. He was also running a small clothing shop to earn a living.

The young imam was already attracting the attention of the Chinese police. He was ordered to obey Chinese restrictions on what he could say to the believers at his mosque, but his family says he sometimes violated them.

In the early 1990s, China was in the midst of a massive campaign against Muslim leaders in Xinjiang. To maintain control of the restive Muslim region, it imposed a series of rules on the mosques. Cameras were installed inside, while police agents attended the services and public servants were warned that they could lose their jobs if they attended.

At the peak of the conflict, terrorists detonated several bombs in the region, including on public buses. China blamed the Uighurs, and hundreds were rounded up and arrested, far more than the small handful who may have been involved in the violent attacks, human-rights groups say. China began to use the word “terrorist” to apply to almost anyone who advocated independence for the Uighurs.

After years of harassment from the police and a term in prison, Mr. Celil decided to flee the country. His family says he managed to leave China for the first time in 1995 to make a pilgrimage to Mecca, the Muslim holy city. A few months later, after a brief return to Kashgar, he fled to Central Asia, making his way eventually to Kyrgyzstan, China's neighbour to the northwest, where he continued in the clothing trade and served as an imam in a Uighur mosque. Both the trips to Mecca and Kyrgyzstan, according to family members in Canada, were made using fake passports. China, they say, never granted Mr. Celil a passport; the first and last legitimate one he held was Canadian.

His family and his lawyer say that's why, in the two years he spent in Kyrgyzstan, the last nine months of which were in a jail cell, Mr. Celil used the name Guler Dilaver.

It was 1998, and the bazaars in Kyrgyzstan were thriving.

Mr. Celil was living in the capital city of Bishkek at the time, selling silk and clothes in the sprawling markets alongside other Uighur traders. There was a sizable Uighur community in the country, but almost all of them were considered illegal, so a black market in passports evolved within the community. According to relatives and friends who knew him at the time, Mr. Celil purchased one. The name on the Turkish document was Guler Dilaver, born in 1955. Using this passport, Mr. Celil lived in Kyrgyzstan for two years, working as a trader but also preaching Islam on the side.

In the middle of 1998, Mr. Celil was picked up by Kyrgyzstani police. According to statements made to the Uighur Canadian Association by both his former cellmate and former lawyer, Mr. Celil was charged with crimes, including “creating hatred among the people,” a charge related to his religious sermons. He spent nine months in jail waiting for a trial. And when that trial finally came, his lawyer at the time alleges, there were Chinese officials in the courtroom watching. Both his lawyer and cellmate say he was eventually acquitted in December of 1998. The first thing he did upon his release, they say, is flee Kyrgyzstan.

During the same period, beginning in 1996, when Mr. Celil first left China, Chinese police were keeping a close watch on his family in Xinjiang. They searched the house almost every month, looking for religious texts and demanding to know his whereabouts, his family says.

His family did not find that surprising. Every family with a son who was trained at a mosque or who had fled the country was routinely raided and searched, they say.

“Of course we were angry about it, but they are the police and so we have no choice,” Sarmeti Celil said. “We are afraid of the police. We suffered a lot of stress. Our lives were always interrupted. There was never anything they wanted in our rooms, so why did they keep searching us?”

Mr. Celil's first step on what would be an arduous journey to Canada began when he crossed the border from Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan. Still using a fake passport, he sought refuge with the Uighur community, eventually meeting a man in a local bazaar who not only gave him refuge, but introduced him to his daughter.

Kamila Telendibaeva and Mr. Celil were married a month later.

“He was educated,” Ms. Telendibaeva recalls. “He knew the Koran, he knew the hadith,” she said, referring to the Muslim holy book and the sayings and deeds of the Prophet Mohammed.

(Mr. Celil's first marriage, to a woman who lived near his family's farm in Xinjiang, had ended in divorce.)

But it was only after Ms. Telendibaeva and Mr. Celil were married that he told her he'd just finished a stint in jail and needed to flee the region. The honeymoon was barely over when, in 1999, Mr. Celil left for Turkey with three fellow refugees. In the summer of 1999, the four managed to enter Turkey through Syria. Ms. Telendibaeva joined them a month later.

The couple had their first child, Mohammad, while in Turkey. About six months after his birth, Mohammad's parents found out their son had serious health problems and need near-constant supervision.

Mr. Celil and his wife applied for refugee status with UNHCR. While the United Nations agency would have performed the initial background check on the couple, Canadian officials would have performed a number of security checks to ensure the refugees needed protection.

In the spring of 2000, their claim was accepted, and in October of 2001, they left for Canada after two years in Turkey.

It was during those two years that Guler Dilaver allegedly killed a man.

According to a letter released by the Uzbek embassy in London, Mr. Dilaver is wanted by Kyrgyzstan police for involvement in the “assassination of the head of Uighur society in Kyrgyz Republic on 28 March, 2000, and terrorist act against the state delegation of Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of China on 25 May, 2000.” The Uzbek letter claims Mr. Celil and Mr. Dilaver are the same person.

A UNHCR spokeswoman said it would be highly unlikely for a refugee-in-waiting to travel outside the country in which he claimed asylum, since he would have no travel documents.

Mr. Celil's Canadian lawyer agrees. “It's just not realistic for this guy to have done that,” said Chris MacLeod. “He would have forsaken his UNHCR status, left his disabled kid and wife, forged documents, made it there and back — it's just not doable.”

The Uzbek embassy letter also claims that Mr. Celil is on an Interpol wanted list. However, the Interpol referred to in the letter is the “Interpol National Central Bureau in Uzbekistan.” Had Mr. Celil been on the Western Interpol list, Mr. MacLeod said, he would have never passed Canadian security checks. “Rest assured that [Canadian immigration officials] did not treat Huseyin any differently than any other Muslim man from Central Asia.”

But the Dilaver allegations wouldn't surface for several more years. In October of 2001, Mr. Celil and his wife had other things on their minds, like their trip to Canada, the first country Mr. Celil could legitimately call home.

There aren't too many Uighurs in Halifax.

After a six-hour trip via Holland, Mr. Celil and his wife touched down in Canada for the first time in late 2001. “It was a bit boring, there was no one in our community,” said Ms. Telendibaeva, who was pregnant with the couple's second child while in Halifax.

They studied English, Mr. Celil delivered food and occasionally cooked for an Arabic restaurant. But after 1½ years, they decided to move to Hamilton. There aren't too many Uighurs there, either, but the Turkish community, with which the couple share a common language, is much larger. They stayed there for two years before moving into a modest home in nearby Burlington.

It was a happy time for the couple. Ms. Telendibaeva became pregnant with their third child. Mr. Celil was back to studying, and volunteered part-time at a Turkish mosque. To top it off, the couple received their Canadian citizenship in November of 2005.

In an indirect way, that was when Mr. Celil's troubles really began.

By then, Ms. Telendibaeva had been away from her family for about six years. Her mother was sick and wanted to see her grandchildren. So in February of 2006, just three months after obtaining Canadian passports, Mr. Celil and his family flew to central Asia. They had no trouble getting visas to Kyrgyzstan, where Mr. Celil had been jailed in 1998, or Uzbekistan, where Ms. Telendibaeva's family lived.

In late March, Mr. Celil went with Ms. Telendibaeva's brother and father to a government office in Uzbekistan to ask for a one-week visa extension, so Mr. Celil's son could recuperate from a circumcision operation before travelling. After waiting for several hours, the three were confronted by Uzbek police, who told them they needed to speak with Mr. Celil. It was the last time Ms. Telendibaeva or her family saw him.

For five days, the family awaited word of Mr. Celil's fate. When nothing came, they went to a Canadian consular office. “[Canadian officials] asked why he was arrested,” Ms. Telendibaeva said. “I told them, ‘go find out.' ”

But by the time Ms. Telendibaeva, pregnant with the couple's fourth child, had to go back to Canada in May, she knew virtually nothing about what was going to happen to her husband.

A few weeks after Mr. Celil's detention, Chris MacLeod received an urgent call at his home in Hamilton, outlining Mr. Celil's plight. Mr. MacLeod's wife is from Iran, and he had met Mr. Celil at social functions. Although it had nothing to do with the kind of law he normally practised — he's a business-litigation expert — he decided to take the case.

It didn't take long before Ottawa became acquainted with Mr. Celil's case. On his way to a meeting in Asia in the spring of 2006, Mr. MacKay met with the Uzbek ambassador. Mr. MacKay said the ambassador initially denied any knowledge of Mr. Celil's whereabouts, even though Mr. Celil was still detained in Uzbekistan at the time, but promised to look into it.

The Uzbeks did look into it. On June 26, they informed Canadian officials that Mr. Celil had been deported to China. Canadian officials would soon see just what China thought of the detained Canadian.

During a trip to Kuala Lumpur in July, Mr. MacKay tried to bring up Mr. Celil's case with his Chinese counterpart, Li Zhaoxing. Upon hearing the detained man's name, a puzzled look came over Mr. Li's face until an aide whispered something in his ear, Mr. MacKay recalled.

“Oh,” Mr. Li said. “You mean the terrorist.” For the rest of the meeting, that's how Mr. Li referred to Mr. Celil.

That meeting contrasted sharply with the one Mr. MacKay had with Ms. Telendibaeva after her husband's detention. By now heavily pregnant, the woman was, as Mr. MacKay saw, deeply distraught.

“The stress and strain was written on her face,” Mr. Mackay said. “Both the consequences and impact [of the Celil case] were obvious from Day 1.”

In October of last year, Prime Minster Stephen Harper visited Toronto. He was there to speak on crime prevention and other issues. But in the meeting room of a Marriot hotel suite, he met Ms. Telendibaeva and her lawyer. By then, Mr. Celil had already been sent to China. It was the first time anyone could recall a prime minister talking in person with the spouse of a Canadian detained abroad. The meeting was scheduled for 10 minutes; it lasted 40.

“That was the turning point,” Mr. MacLeod said. “The Prime Minister could put a face to the file.”

The meeting was perhaps the most direct sign that Mr. Harper was taking the case seriously. He brought Mr. Celil's case up with Chinese President Hu Jintao at the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation forum in Hanoi in November, and publicly stated he wouldn't put the countries' economic relationship ahead of human rights.

Information out of China in the months after Mr. Celil's deportation was scarce. Relying on second- and third-hand reports, his family first heard that he was to be executed for vague terrorism charges; then that he had been sentenced to 15 years, a rumour that turned out to be false; then that he had been granted another trial.

His whereabouts in China and the details of the charges against him are unknown. The first time anyone other than his prison guards got a look at him was about two weeks ago, when he appeared before a court in northwest China. Canadian consular officials didn't show up for the hearing, clearly angering Mr. Harper. The highest offices in Ottawa quickly instructed Canadian officials in China to trek northwest and try to meet with Mr. Celil and observe the next stage of his trial.

But as far as Mr. Celil's family knows, there is no next stage; his six-hour appearance in early February was the trial. The next time he shows up in a courtroom, they suspect, will be to hear his sentence.

These days, much of Ms. Telendibaeva's time is taken up with her children. Her oldest son needs a wheelchair and near-constant supervision; her youngest, born last summer, has never seen his father.

Mr. Celil's imprisonment has made life complicated for 29-year-old Ms. Telendibaeva in more ways than one. Her youngest son's birth certificate is proving difficult to obtain; he cannot inherit his father's last name without his father's signature. She had trouble getting six-month-old Zubeyir into the United States last month when she went to testify about Mr. Celil's case before the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, which gives policy recommendations to the President and Congress. Ms. Telendibaeva's mother arrived in Canada last year to help her daughter take care of the children, and renewing her visa is yet another challenge.

Sitting in the cramped living room of her small Burlington house, Ms. Telendibaeva speaks in broken but improving English. Welfare pays the $411 rent on a home that, since last year, has been visited by myriad journalists, politicians and activists from around the world. The walls are decorated with pictures of Mecca, religious scripture and a framed drawing of a mansion, a helicopter and a speedboat. Above the drawing are the words: “All I want is world peace and . . .”

Some time in the next month, Ms. Telendibaeva's husband will make another court appearance in China. His trial might continue, or he might be sentenced. Canadian officials might get to meet with him, or they might not. He might see his wife and children again, or he might not.

Asked what message she would send to her husband if she could, Ms. Telendibaeva paused, the incessant noise of children's toys blaring in the background.“I don't know,” she said finally. “We miss him.”

The charges

Huseyin Celil's lawyer says he has been charged under two articles of the Chinese criminal code.

Article 103: “Whoever organizes, plots or acts to split the country or undermine national unification, the ringleader, or the one whose crime is grave, is to be sentenced to life imprisonment or not less than 10 years of fixed-term imprisonment; other active participants are to be sentenced to not less than three but not more than 10 years of fixed-term imprisonment; and other participants are to be sentenced to not more than three years of fixed-term imprisonment, criminal detention, control, or deprivation of political rights.”

Article 120: “Whoever organizes, leads, and actively participates in a terrorist organization is to be sentenced to not less than three years but not more than 10 years of fixed-term imprisonment; other participants are to be sentenced to not more than three years of fixed-term imprisonment, criminal detention or control. Whoever commits the crime in the preceding paragraph and also commits murder, explosion, or kidnapping is to be punished according to the regulations for punishing multiple crimes.”

*****

The plight of the Uighurs

Uighurs are Turkic-speaking Asians who live mainly in western China. Their history has been interwoven with that of China since they rose to prominence in the eighth century, when they established their first true state in Mongolia. Relations between the Chinese and the Uighurs were never entirely comfortable, however, and the Chinese considered them a barbarian people.

In fact, the Uighurs were advanced in art, architecture, music and medicine, and they practised a complex agriculture, using an extensive system of canals for irrigation. Their history had included adherence to shamanism, Manicheism and Buddhism, but at about the turn of the 10th century, they embraced Islam.

In 1911, after the Nationalist Chinese overthrew the Manchu dynasty and established a republic, the Uighurs, who had been forcibly annexed by the Manchu rulers, staged a series of uprisings in favour of independence. Two successful attempts to set up their own republic were overthrown by military intervention.

After the Chinese revolution in 1949, the Uighurs fell under Communist Party rule. The government flooded Xinjiang, the province in which most Uighurs live, with Han Chinese migrants; pushed the locals to learn Mandarin; and restricted the practice of Islam.

Relations between the modern Chinese state and its Uighur minority are still fraught. Beijing believes the Uighurs pose a separatist threat and Uighurs complain that oil and gas production in Xinjiang has been conducted at their expense, without just recompense. In the mid-1990s, Uighurs carried out widespread protests and even bombings against Chinese rule.

China, for its part, has launched a crackdown on the Uighurs, arresting and executing many in trials criticized by human-rights groups as unfair. China has long linked the region to terrorism, and has attacked what it says are terrorists and training camps in the province.

But while many Uighurs want greater autonomy for their region, few advocate the cause of independence that motivates a handful of extremist groups.

Human-rights observers believe China uses the idea of a Uighur terrorist threat as an excuse to crack down on all dissent. They accuse the government of carrying out arbitrary arrests, unfair trials, torture and religious discrimination in the region.

*****

Seeking a haven around the world

Huseyin Celil's globetrotting began with his efforts to escape first Chinese and then Kyrgystan authorities. His story ends up back in China, where he is now imprisoned.

Start: China

1994: Kyrgyzstan

1998: Uzbekistan

Turkmenistan

Iran

Iraq

Syria

1999: Turkey

Oct., 2001: Toronto

Halifax

2003: Hamilton

2005: Burlington

Feb., 2006: Moscow

March, 2006: Kyrgyzstan

June, 2006: China

posted February 23, 2007 at 10:21 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (157)

February 16, 2007

Chinese New Year

...and surprise! I'll be arriving back in New Jersey for a one-month visit on Monday, February 19th. Why not drop me a line so we can get together, eh old friend?

posted February 16, 2007 at 02:04 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (35)

February 11, 2007

The Kashgar Experience

Howard French has written an article about Kasghar in the Travel section of today's New York Times. For those of you who own a copy of Lonely Planet or have visited Kasghar before, there's nothing really new... just the same ol' "crossroads of Central Asia" blah blah blah. Still, you can read the full article below.

Luckily, I've been waiting for Kasghar to come into the news so I could debut a new music video on this site. Wushur Kari's video below for "Ziyarat" is an excellent introduction to the atmosphere of Kasghar that so many visitors find alluring. The video gives you a good feel for just how different Xinjiang is from China's densely-populated East. Wushur visits many of the Kasghar area's top sites and partakes in a boisterous Uyghur religious celebration:

Don't forget to turn up the volume on your subwoofer for the optimal listening experience.

And make sure you watch the video until the end! The last two minutes are the best part, shot during what I believe is last year's Roza Heyt (Eid ul-Fitr) celebrations outside Id Kah Mosque. The hypnotic, whirling mass of dancing men known as the Sama is something not often seen... only twice a year (the other time is during Kurban) and only in places where large groups of Uyghurs gather to celebrate.

Check out the Chinese Ministry of Culture's description of the Sama dance. And while you're at it, take a look at Kashgarkid's video from the Roza Heyt celebrations in 2005 here.

Enjoy!

Viewing Two Chinas From a Stop on the Silk Road

February 11, 2007

Explorer | Kashgar

The New York Times

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

GLOBALIZATION has always been a dodgy term. As a clever neologism, it flatters our need to believe that the times we inhabit offer something truly new. Pause to think about it more clearly, though, and even a basic knowledge of geography or history turns up examples in almost every corner of the globe of the kinds of intercourse that turns global into globalization.

Better yet, there are places like Kashgar, an ancient Silk Road oasis town in the far west of China, where for centuries great swaths of disparate peoples have come together in a jumble just about as colorful as one could want or imagine.

My first experience of this came just yards from my hotel door on the groggy first morning of my stay in November. Groggy because I had flown there from Shanghai the night before, which meant seven hours in the air and a change of planes in Urumqi, the booming capital of China's Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.

Why bother coming to Kashgar at all, you might ask, given that it is neither the most obvious nor accessible choice for an additional stop beyond, say, Beijing or Shanghai on your average China trip itinerary?

For one thing, this city has few rivals in China for longevity when it comes to defining what it means to be a crossroads.

For at least two millenniums, Kashgar was one of the most prosperous market cities on what eventually became known as the Silk Road. Caravans of camels sometimes stretching for miles made their way through its walls, carrying silk or spices, silver and gold between East and West.

Separated from Pakistan by the Karakoram mountain range, whose 15,500-foot Khunjerab Pass is the world's highest paved border crossing, this area was also one of Islam's main points of entry into China. Ever traditionalist, conservative Kashgar remains perhaps the most important Islamic center for Chinese Muslims today.

The best answer to the question of why travel to China's westernmost city, though, is the visceral response you get from plunging into Kashgar's streets, as I did that first morning with my guide, Abdul. We made our way into the heart of the old city, once protected by an imposing earthen wall, whose sloping remains can still be seen.

As you leave the wide boulevards of modern Kashgar behind and ascend a small hillside lane, the jolt you receive constitutes one of the most powerful feelings that travel can provide — of leaving one world and entering another. In Kashgar's case it is a matter of a few yards from the familiar China of onrushing modernization to places that, but for a few details — like the occasional car nosing its way through streets thick with merchants and foot traffic — seem scarcely touched by time.

The high, old brick walls of closely spaced houses pressed in on us. Bearded men huddled in conversation, some working their prayer beads as they listened. A man in a battered barber's chair sat inclined, had his face lathered and massaged vigorously, and then was shaved with a straight razor.

A little way ahead, a clutch of women in veils approached, the first evidence of what I came to understand as a general rule here: once a woman is beyond her 20s, the veil is pretty much standard attire. That befits a place where in most old neighborhoods there is a mosque every hundred yards or so.

I knocked on the door at one and was welcomed by the friendly man with a beard combed to a fine white point. He was both groundskeeper and muezzin, or caller to prayer, and he sat with us for an hour, offering tea and then turning on the naked lanterns in the pillared and hitherto dark main prayer hall. The light revealed beautiful blue ceramic tiles at the altar etched with calligraphic prayers and a proud smile on the face of our host.

China's Uighur minority, which is the largest ethnic group in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, is almost entirely Sunni, and is subjected to very tight controls by a government wary of both terrorism and of longstanding separatist sentiments.

At the end of our visit with him, the muezzin climbed the rough cement staircase to a platform linking his twin minarets, explaining that it was from there that he called the faithful to prayer. What he didn't explain, careful to be discreet, is that the government doesn't allow the use of loudspeakers or megaphones, as is common in many Islamic countries.

At a small junction in the road, we came across a crowd of men standing engaged in a lively discussion. I wondered if there had been an incident but was told that they were making preparations for a wedding.

Around the corner, next to a bakery where freshly made flatbread lay cooling on an iron grill, a group of women — the female half of the wedding party — stood discussing their own arrangements.

When I turned the next corner in this maze of narrow streets, there was yet another discovery: Stalin lives. Or at least Stalin knickknacks do. All over China one can also find Mao memorabilia from the Cultural Revolution, from Little Red Books to pins and banners emblazoned with the Great Helmsman's image. Here, though, was a shopkeeper in a little hole in the wall. He had hung a vintage poster of Uncle Joe beaming confidently in front of his shop. It served as an appropriate reminder of the region's geography.

Indeed, as much as a Silk Road outpost, Kashgar was one of the main stalking grounds of the Great Game, as the shadowy competition between Russia and Britain for power and influence in Central Asia came to be called. The rival powers chose Kashgar as their listening posts for Afghanistan, India, China and the Islamic underbelly of the Russian empire, and from here each employed diplomat-spies to plot their moves from rival consulates.

In Kashgar today, as in much of China, one gets the impression that a very intense war has been waged on the country's cultural and tourism assets.

Signs of genuine local culture are so often poorly preserved, when they have not been destroyed altogether. China deserves credit for its formidable achievement of development, which has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in a generation, but in most places the price for this has been the imposition of generic forms that are often tasteless and sometimes hideous.

Because of its remoteness, Kashgar is behind the curve, and for once that's good. But even Kashgar is coming under the pressure of Chinese-style homogenization, though, and that's another reason to visit soon.

The old Kashgar open-air market, which once drew as many 100,000 traders from all over the region each Sunday to haggle over everything from carpets to cattle, was a direct descendant of the trade brought here on the great camel trains. But it has fallen victim to what some will fancy is progress. In this case, progress has come in the form of a glorified hangar with cement floors, where bored-looking merchants tend regimented stalls all day. There may still be a big crowd on Sundays, but for the soul of the old weekly bazaar one must look elsewhere.

One place is a livestock market at the edge of town that used to be held in the main market but was moved when the cement was poured. Also held on Sunday, this is a place where thousands of rugged central Asian cowboys and peasants come to buy and sell cattle, camels, sheep and horses.

By midmorning, dust hangs thick in the air from all of the stamping hoofs, but coping with that is a small price to pay for the heaping doses of color as craggy-faced men come together in clusters and bargain loudly over the beast of their choice.

For my money, Friday prayer at the central mosque has become the week's new main event. Non-Muslims are not allowed to enter the mosque during the services, but the mosque sits in the middle of a huge square, which is surrounded by markets where foreigners are welcome.

About 20,000 people show up most Fridays for the midafternoon prayer, filling the mosque and spilling out on an apronlike staircase that wraps around the entranceway. Men to one side, women to the other, the faithful perform their rites, prostrating themselves repeatedly on little prayer rugs and standing, gazing into their palms, which they hold before them as the recite their prayers.

Beggars appear here by the dozens, too, many of them badly deformed. Their troubles are rewarded when the huge crowds of faithful emerge and drop coins and crumpled bills into their cups as alms.

Thirty minutes or so after the service is over, the mosque has fully emptied, but the square has not. There, people lay out goods for trade on sheets, and buy and sell shoes and clothing, prayer books and even eyeglasses.

For others, as for me, it was time for a late lunch of skewered lamb and noodles, and to savor the aroma of tea and freshly baked bread in the afternoon air.

VISITOR INFORMATION:

GETTING THERE

Kashgar can only be reached by air from Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Urumqi, in turn, can be reached via a variety of Chinese cities, including Beijing, Shanghai and Xian. Beyond the regular China visa, there are no special visa requirements for travel to Xinjiang.

Dollars are accepted but not preferred. A.T.M.'s around the city can connect travelers to their overseas bank accounts, and money can be changed in banks and hotels.

WHERE TO STAY

The former Russian consulate in Kashgar has been converted to the Seman Hotel (337 Seman Road; 86-998-258-2129). It is a dark, slightly down-at-the-heels affair that nonetheless still exudes the atmosphere of the era, with its look of a minor Russian palace with pastoral murals and Cyrillic inscriptions. Even if you don't stay there, a stop at the hotel's outdoor restaurant for a lunch of laghman, a tasty, mildly spicy Central Asian noodle dish, is a good excuse to visit. Standard rooms start at about 120 yuan a night, or about $15 at the rate of 7.9 yuan to the dollar.

The Chini Bagh Hotel (144 Seman Road; 86-998-298-3234) is a large, modern establishment set in a complex that also includes the British consulate. Deluxe rooms start at about 220 yuan a night.

Both the Seman and the Chini Bagh can arrange a guide for you, at a day rate of 150 yuan and 100 yuan, respectively.

WHERE TO EAT

Popular restaurants include the Orda (167 East Renmin Road; 86-998-265-2777), which specializes in local cuisine, like samsas (dumplings with mutton filling) and flatbreads. Four people could have a very large meal for about $20.

The same is true for the Intizar Restaurant (33 West Renmin Road, 86-998-258-5666), where in addition to meat dishes, patrons might also be offered a dish of mung bean noodles mixed with julienned radishes, carrots and cabbage, all tossed with a vinegar dressing.

In the old part of Kashgar, visitors will find a wide selection of bread stalls, noodle stands and small restaurants, as well as fruit and vegetable vendors.

posted February 11, 2007 at 09:55 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (135)

February 09, 2007

Chunking Express

Great transportation news for those of you looking to visit Northwest China (and for those few of us looking to travel anywhere else):

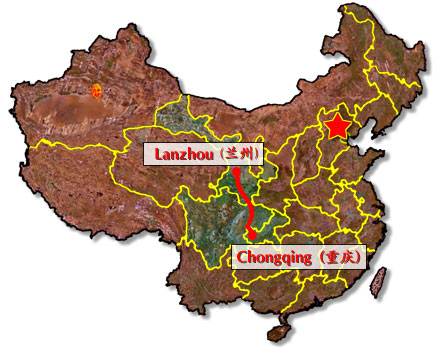

On February 2nd, the main leaders from the Ministry of Railways, Gansu Provincial Government, Sichuan Provincial Government and Chongqing Municipal City signed the "Summary of the Working Conference of Accelerating the Preparation for the Lanzhou - Chongqing Railway Project" in Beijing. According to the agreement, the construction of the said railway will begin within 2007. The 900km-long Lanzhou - Chongqing railway is designed in accordance with a speed allowance of over 200km/h. Upon completion, it will take around four hours to travel from Lanzhou City to Chongqing City by train.

Four hours from Lanzhou to Chongqing! That's a rail journey that currently would set you back between 19 and 27 hours... give or take a huge pain in the ass.

The new route isn't exactly clear. The official Xinhua announcement above lists only Gansu, Sichuan, and Chongqing as participants, leading me to believe the route shown on this mysterious map of China's future rail network. (It's the same route I've mapped out above.)

But then I found a contradictory press release from the Asian Development Bank, an organization one would hope knows the path of the railways it helps to finance:

Asian Development Bank is helping to design a project to construct a railway through mountainous parts of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Sichuan provinces and Chongqing municipality in the People's Republic of China through a grant of US$500,000.

The grant will strengthen the Government's planning for the project, which would involve construction of 817 kilometers of electrified line and 21 new stations linking the city of Lanzhou in the northwest to Chongqing in the southwest. Because of the hilly terrain, some three quarters of the route's length will comprise tunnels and bridges.

The project area will encompass 13 counties and cities with a total population of about 15 million, two thirds of which is rural.

If the line is going to pass through Shaanxi as stated above, it would have to be a bit further east than what's shown on my map.

In any case, being able to travel conveniently between Lanzhou (which is the gateway to China's vast northwest) and Chongqing (the gateway to both the southwest and the Yangtze River) is going to open up a whole new world of rail travel possibilities. Yunnan, Sichuan, Guizhou, Guangxi, Hunan... the entire south will be at my disposal.

Have I mentioned how big a fan I am of the Chinese rail system?

Construction of Lanzhou - Chongqing Railway to Begin

6 February 2007

China Industry Daily News

(Feb. 6, 2007)- On February 2nd, the main leaders from the Ministry of Railways, Gansu Provincial Government, Sichuan Provincial Government and Chongqing Municipal City signed the "Summary of the Working Conference of Accelerating the Preparation for the Lanzhou - Chongqing Railway Project" in Beijing. According to the agreement, the construction of the said railway will begin within 2007. The 900km-long Lanzhou - Chongqing railway is designed in accordance with a speed allowance of over 200km/h. Upon completion, it will take around four hours to travel from Lanzhou City to Chongqing City by train.

Asian Development Bank Helping Plan Lanzhou-Chongqing Rail Project in China

29 January 2007

ACN Newswire

Manila, Philippines, Jan 29, 2007 - (ACN Newswire) - Asian Development Bank (ASX: ATB) is helping to design a project to construct a railway through mountainous parts of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Sichuan provinces and Chongqing municipality in the People's Republic of China through a grant of US$500,000.

The grant will strengthen the Government's planning for the project, which would involve construction of 817 kilometers of electrified line and 21 new stations linking the city of Lanzhou in the northwest to Chongqing in the southwest. Because of the hilly terrain, some three quarters of the route's length will comprise tunnels and bridges.

The project area will encompass 13 counties and cities with a total population of about 15 million, two thirds of which is rural. Most people living in the project area work in low yielding agriculture. Despite the area's rich natural resources and tourist potential, the people have remained largely poor and cut off from mainstream development due to lack of transport.

No expressway or railway connects this region. The railway link will provide the shortest north-south rail route from Xinjiang, Baoji, and Lanzhou to Chongqing and Kunming. The line will also connect Central Asia (Alashankou-Xinjiang-Lanzhou) with Southeast Asia (Chongqing-Guiyang-Kunming-Hekou).

"The planned railway will, during its operation and construction, increase local people's access to jobs, markets and services and give them an opportunity to improve their living standards," says Manmohan Parkash, ADB Senior Transport Specialist and team leader for the project.

The project is planned as a joint venture between the Ministry of Railways (MOR) and the Chongqing, Gansu, and Sichuan local governments and will be implemented by MOR.

Among the planning activities planned under the technical assistance (TA) grant project are field surveys, document reviews, data analysis, and consultations with stakeholders, including government officials, affected people, and project beneficiaries. The TA is expected to be completed by around May 2007.

ADB's strategy for China's railway sector focuses on expanding the system in underserved and poor areas, modernizing key routes to improve transport efficiency, and commercializing operations to ensure efficient running of the rail service.

About ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK:

ADB, based in Manila, is dedicated to reducing poverty in the Asia and Pacific region through pro-poor sustainable economic growth, social development, and good governance. Established in 1966, it is owned by 64 members - 46 from the region.

In 2005, it approved loans and grants for projects totaling $6.95 billion, and technical assistance amounting to $198.8 million.

Contact:

Tsukasa Maekawa

Email: tmaekawa@adb.org

Tel:+632 632 5875; Mobile: +63 918 939-9059

Graham Dwyer

Email: gdwyer@adb.org

Tel:+632 632 5253; Mobile: +63 920 938-6487

Source:

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK

posted February 09, 2007 at 11:36 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (48)

February 07, 2007

Sichuan Natural Gas Smackdown

Sure, Sichuan's got tasty food and the world's biggest Buddha, but Xinjiang's got gas! Hrmmm. That doesn't sound right... but still, it's the truth:

The restive region of Xinjiang in northwest China has become the country's top gas producer, with an output of 16.1 billion cubic metres of gas in 2006.

The region's output, which increased by 5.5 billion cubic metres compared to 2005, overtook southwestern Sichuan Province, which produced an estimated 12 billion cubic metres....

How do ya like them apples, Sichuan? Your time is over! This is a new era... an era that belongs to Xinjiang. (Please feel free, however, to continue sending us your poor farmers to pick our cotton and your skilled chefs to make my lunch.)

Xinjiang becomes China's top gas producer

6 February 2007

The Press Trust of India Limited

Beijing, Feb 6 (PTI) - The restive region of Xinjiang in northwest China has become the country's top gas producer, with an output of 16.1 billion cubic metres of gas in 2006.

The region's output, which increased by 5.5 billion cubic metres compared to 2005, overtook southwestern Sichuan Province, which produced an estimated 12 billion cubic metres, chairman of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Ismail Tiliwaldi said.

The Tarim, Karamay and Tuha oilfields, the three major fields in the region, produced 11 billion, 2.88 billion and 1.65 billion cubic metres of gas respectively last year.

Xinjiang, where Islamic militants are waging a low-intensity struggle against the communist authority, has an estimated natural gas reserve of 10 trillion cubic metres, accounting for a quarter of China's total. The region's proven reserve of natural gas is 1.2 trillion cubic metres.

The Tarim oilfield is a source for the 4,000-km pipeline project to bring natural gas from western China -- primarily Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and Shaanxi Province -- to 34 cities in the economically developed eastern regions.

Last year, Xinjiang supplied 9.8 billion cubic metres of gas to eastern regions, Xinhua news agency reported.

Xinjiang last month witnessed the biggest counter-terrorism drive by Chinese security agencies in which 18 militants were killed and 17 others were arrested. In the January 5 raid, police also seized 22 hand grenades and over 1,500 anti-tank weapons.

One Chinese policeman was killed and another wounded in the gun battle with separatists belonging to the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM). ETIM was listed by the United Nations as a terrorist organisation on September 11, 2002, and was included in a list of "East Turkistan" terrorist organisations issued by the Chinese Ministry of Public Security in 2003.

Other identified East Turkistan terrorist organisations are the East Turkistan Liberation Organisation (ETLO), the World Uygur Youth Congress (WUYC) and the East Turkistan Information Centre (ETIC).

Muslim Uygur militants are waging a struggle to make Xinjiang an independent state called 'East Turkistan'.

posted February 07, 2007 at 03:21 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (26)

February 06, 2007

10 Years Later

Can't talk about these things here, but why not have a look for yourself?

posted February 06, 2007 at 06:17 AM unofficial Xinjiang time

February 05, 2007

General Tso's Chicken

There's an article in this weekend's New York Times Magazine about the origin of General Tso's Chicken. Strangely, the article doesn't really provide the answer to this life-long question of mine, merely filling in some details on the most likely history. The article doesn't even answer the question of why exactly the dish was named after General Tso, better know in China as Zuo Zongtang (左宗棠). Still, the story involves the Nationalist flight to Taiwan and Henry Kissinger, so it's worth a read. There's even a free recipe for an "authentic" version of the dish.

So, what does General Tso's Chicken have to do with this blog besides the fact that I've eaten the dish about a thousand times in my life? Well, aside from supressing the Taiping Rebellion in 1860, Zuo was also responsible for putting an end to Yakub Beg's state of Kashgaria, incorporating the "new territory" of Xinjiang into the Qing empire in 1884. Yakub Beg, as it turns out, died under mysterious circumstances here in Korla in 1877. And that's enough of a connection for me!

You can read the article and the recipe for General Tso's Chicken below.

Food: The Way We Eat

Hunan Resources

By FUCHSIA DUNLOP

The New York Times Magazine

Published: February 4, 2007

General Tso’s (or Zuo’s)chicken is the most famous Hunanese dish in the world. A delectable concoction of lightly battered chicken in a chili-laced sweet-sour sauce, it appears on restaurant menus across the globe, but especially in the Eastern United States, where it seems to have become the epitome of Hunanese cuisine. Despite its international reputation, however, the dish is virtually unknown in the Chinese province of Hunan itself. When I went to live there four years ago, I scoured restaurant menus for it in vain, and no one I met had ever heard of it. And as I deepened my understanding of Hunanese food, I began to realize that General Tso’s chicken was somewhat alien to the local palate because Hunanese people have little interest in dishes that combine sweet and savory tastes. So how on earth did this strange, foreign concoction come to be recognized abroad as the culinary classic of Hunan?

General Tso’s chicken is named for Tso Tsung-t’ang (now usually transliterated as Zuo Zongtang), a formidable 19th-century general who is said to have enjoyed eating it. The Hunanese have a strong military tradition, and Tso is one of their best-known historical figures. But although many Chinese dishes are named after famous personages, there is no record of any dish named after Tso.

The real roots of the recipe lie in the chaotic aftermath of the Chinese civil war, when the leadership of the defeated Nationalist Party fled to the island of Taiwan. They took with them many talented people, including a number of notable chefs, and foremost among them was Peng Chang-kuei. Born in 1919 into a poverty-stricken household in the Hunanese capital, Changsha, Peng was the apprentice to Cao Jingchen, one of the most outstanding cooks of his generation. By the end of World War II, Peng was in charge of Nationalist government banquets, and when the party met its humiliating defeat at the hands of Mao Zedong’s Communists in 1949, he fled with them to Taiwan. There, he continued to cater for official functions, inventing many new dishes.

When I met Peng Chang-kuei, a tall, dignified man in his 80s, during a visit to Taipei in 2004, he could no longer remember exactly when he first cooked General Tso’s chicken, although he says it was sometime in the 1950s. “Originally the flavors of the dish were typically Hunanese — heavy, sour, hot and salty,” he said.

In 1973, Peng went to New York, where he opened his first eponymous restaurant on 44th Street. At that time, Hunanese food was unknown in the United States, and it wasn’t until his cooking attracted the attention of officials at the nearby United Nations, and especially of the American secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, that he began to make his reputation. “Kissinger visited us every time he was in New York,” Peng said, “and we became great friends. It was he who brought Hunanese food to public notice.” In his office in Taipei, Peng still displays a photograph of Kissinger and himself raising wineglasses at the restaurant.

Faced with new circumstances and new customers, Peng invented dishes and adapted old ones. “The original General Tso’s chicken was Hunanese in taste and made without sugar,” he said. “But when I began cooking for non-Hunanese people in the United States, I altered the recipe.” (Though others have since laid claim to it.) In the late 1980s, having made his fortune, he sold out and returned to Taipei. His New York venture was to have enormous impact on the cooking of the Chinese diaspora. Not only General Tso’s chicken but also other dishes that he invented have been widely imitated, and his apprentices have helped to disseminate his style of cooking.

The final twist in the tale is that General Tso’s chicken is now being adopted as a “traditional” dish by some influential chefs and food writers in Hunan. In 1990, Peng returned to Changsha, where he opened a restaurant that included the creation on its menu. The restaurant did not last long, and the dish was never popular (“too sweet,” one local chef told me), but some leading figures in the culinary establishment learned how to make it. And when they began to travel abroad to give cooking demonstrations, it seems quite likely that their overseas audiences would have expected them to produce that famous “Hunanese” recipe. Perhaps it would have seemed senseless to refuse to acknowledge a dish upon which the international reputation of Hunanese cuisine was largely based. Maybe it would have been embarrassing to admit that the dish was a product of the exiled Nationalist society of Taiwan. Whatever their motivations, they began to include General Tso’s chicken in publications about Hunanese cooking, especially those aimed at a Taiwanese readership.

But even if General Tso’s chicken is an invented tradition, it has to be seen as a part of the story of Hunanese cuisine. After all, it embodies a narrative of the old Chinese apprentice system and the golden age of Hunanese cookery, the tragedy of civil war and exile, the struggle of the Chinese diaspora to adapt to American society and in the end the opening up of China and the re-establishment of links between Taiwan and the mainland.