« April 2007 | HOME PAGE | June 2007 »

May 31, 2007

Caption Contest #4

UPDATE: And the winner is... ME! No, not me, "me". I've taken the liberty of punching up his excellent caption, which now reads,

"Learning to 'look the other way' in the face of injustice often requires rigorous training."

Congratulations, me! You're funny.

--------------------------------

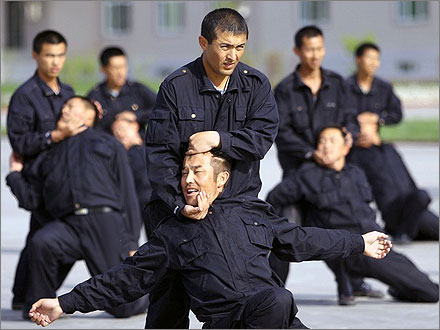

It's been more than three months since my previous caption contest, and not without good reason. The response I got last time was overwhelmingly weak. Obviously, though, I'm not one to learn from my mistakes... so I'm giving it another try. Here's the photo for the fourth caption contest:

I know that it's uncouth to reveal what the photo actually depicts before the contest is over... but this time, reality will probably be funnier than most of your captions. The photo shows prison guard recruits undergoing physical combat training in Urumqi. The kicker is that the apprehensive fellow administering the choke hold is a Uyghur, while his "victim" is Han Chinese. Priceless!

Damn it. Now I've gone and ruined everything. Oh well... the contest is open until Sunday, June 10th, at midnight Beijing time.

posted May 31, 2007 at 12:30 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (55)

May 30, 2007

Let My People Go

The Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed letter by exiled Uyghur leader Rebiya Kadeer today, in which she protests the imprisonment of two of her sons. Note: the words of this extremist splittist-terrorist should be read with extreme caution. The great motherland is indivisible!

Nothing compares to a mother's pain when her children are suffering. The anguish is even greater when the suffering is designed as an act of retaliation by a vindictive government determined to punish those who speak out against its egregious human-rights violations.

Upon my release in 2005 after five years in a Chinese prison, I was warned by the Chinese authorities not to speak out on human rights. I should not forget that I had family in China, I was told.

Fairly standard stuff from Rebiya, but still powerful. Interestingly, she doesn't quite jump on the oh-so chic "Genocide Olympics" bandwagon, preferring to criticize China's domestic rather than international behavior. Still, the fact that she even mentions the Olympics in passing shows what a public relations pain-in-the-ass China is going to encounter as the games approach.

With more than fourteen months to go, China is already facing Olympic-related protests over Sudan and Tibet. How long will it take before Xinjiang, democracy, Taiwan, undervalued currency, human rights, and the weak rule of law are all rolled into the same icy snowball? My suggestion: Zhongnanhai should hire Imagethief to cover their asses. Of course, I don't really believe that there will be an Olympic boycott by the nations that really count (USA! USA! USA!)... the 1980 and 1984 Olympics were just too lame, and nobody in the global community wants to watch that on TV for two weeks.

Towards the end of her plea, Rebiya really gets to the point:

True rule of law is still a foreign concept in China, for any ethnic group, including the majority Han Chinese. Imprisoning its own people and stripping them of their legal rights at the whim of the authorities is just another way that the Chinese government seeks to eliminate any form of dissent.

China will only become a great nation worthy of world-wide respect when it adheres to international legal and human-rights standards throughout its territory, and can guarantee those standards to all its citizens.

Word! You can read the full op-ed piece below.

P.S. You should really check out that Tibet piece in The Times. People are always writing to ask me about traveling to Tibet without a travel pass... it seems that as of this month, things have become decidely more difficult.

My Chinese Jailers

By Rebiya Kadeer

30 May 2007

The Wall Street Journal

Nothing compares to a mother's pain when her children are suffering. The anguish is even greater when the suffering is designed as an act of retaliation by a vindictive government determined to punish those who speak out against its egregious human-rights violations.

Upon my release in 2005 after five years in a Chinese prison, I was warned by the Chinese authorities not to speak out on human rights. I should not forget that I had family in China, I was told.

The Chinese government certainly lived up to its word. My family has been under constant pressure from authorities and my children have been repeatedly detained, tortured or imprisoned. Now my son Ablikim Abdureyim has joined his youngest brother Alim in prison. Ablikim received a nine-year sentence from a Chinese court on charges of "instigating and engaging in secessionist activities."

The real reason for his conviction is my human-rights activism on behalf of the 10 million Turkic Uighurs who live in China's Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, the former East Turkestan. Constantly being labeled terrorists for even the most modest attempt to preserve their unique culture, ethnic background and Muslim faith, Uighurs in Xinjiang continue to suffer under Beijing's repression and forced cultural assimilation. China's long and powerful arm prevents them from finding safety in countries bordering Xinjiang, and Uighurs are harassed by Chinese agents even in Europe and the U.S.

Ablikim's arrest, detention, trial and sentence were all in violation of China's Constitution: My son should have had access to a lawyer; he did not. My son should have had the right to a public trial; yet no family member was allowed to attend his trial or even notified of its existence. Numerous attempts to simply determine his condition were met with stonewalling and frustration.

Unfortunately, mine is just one of countless Uighur families that have been devastated by the Communist Party's use of vaguely defined "state security crimes." In the same week, and in the same court that my son was sentenced to nine years imprisonment, Uighur-Canadian Huseyin Celil was sentenced to life in prison on charges of "terrorist activities" and "plotting to split the country." No evidence against Mr. Celil was made public. In addition, Beijing acted in defiance of international law by refusing to acknowledge his Canadian citizenship and denying him consular assistance.

In recent years, and especially as the 2008 Beijing Olympics approach, Chinese leaders have repeatedly claimed progress on human rights. President Hu Jintao has again and again stressed the importance of respecting the rule of law as a cornerstone of a new and improved China. In a speech at Yale University last year he promised to "protect people's freedom, democracy and human rights according to law."

Yet true rule of law is still a foreign concept in China, for any ethnic group, including the majority Han Chinese. Imprisoning its own people and stripping them of their legal rights at the whim of the authorities is just another way that the Chinese government seeks to eliminate any form of dissent. Polished political leaders in Beijing are eager to say what they believe the world wants to hear, while other government officials, particularly on the local level, routinely break the laws of their own country. All too often the international community is content to listen to the false promises of China's politicians and ignore the miserable reality of China's human-rights conditions.

China will only become a great nation worthy of world-wide respect when it adheres to international legal and human-rights standards throughout its territory, and can guarantee those standards to all its citizens. If Beijing really wants to show the world that it is serious about improving its human-rights record, releasing my two sons and Huseyin Celil would be a good place to start.

---

Ms. Kadeer is the president of the Uyghur American Association and World Uyghur Congress.

posted May 30, 2007 at 02:20 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (38)

May 26, 2007

Breaking Ground

I don't usually blog about my business activities here in Xinjiang, preferring to keep to things either very public (e.g. train derailments) or very personal (e.g. orange toxic mold under my bed). My general thinking is ― and I think lots of other bloggers agree with me on this ― what good could possibly come from blogging about my business? Lord knows I'm already worried enough about customers searching for my name in Google and coming up with goofy old pictures of me and Tom Brokaw.

In any case, I'm only now touching lightly upon the topic of my business because today we held a groundbreaking ceremony for our fancy-schmancy new sundried tomato plant. I snapped the above photo on my Motorola SLVR... it was like a little parade in honor of me and my colleagues. There were Mongol beauties (pink), Uyghur beauties (multicolored), a terrible elementary school brass band, firecrackers, backhoes... ribbons to be cut. Heck, I even made a small speech in Chinese and shoveled dirt for the local TV and newspaper reporters who were ordered to cover the event.

Of course, afterwards came the baijiu, lunch, the inevitable loss of that lunch, and a five-hour nap. But whaddya gonna do? Not a bad day overall.

posted May 26, 2007 at 11:34 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (32)

May 21, 2007

The Sunday Cockfight

I went out to a village in the countryside today with a few friends to pick mulberries. One of the best things about living in Xinjiang is the availability of locally-grown fresh fruit all summer: first watermelon, then mulberries, apricots, all sorts of other melons, tomatoes, red dates, fragrant pears, and apples. The trip also included lunch at a Uyghur friend of a friend's house: kebabs, polo, three types of naan bread, cold beer, some dry red wine, and a hunk of jalapeno pepper jack cheese that I scored in Urumqi.

I went out to a village in the countryside today with a few friends to pick mulberries. One of the best things about living in Xinjiang is the availability of locally-grown fresh fruit all summer: first watermelon, then mulberries, apricots, all sorts of other melons, tomatoes, red dates, fragrant pears, and apples. The trip also included lunch at a Uyghur friend of a friend's house: kebabs, polo, three types of naan bread, cold beer, some dry red wine, and a hunk of jalapeno pepper jack cheese that I scored in Urumqi.

After gorging on huge chunks of lamb and buckets of mulberries, we lay around in a stupor for about thirty minutes... and then the questions was asked: does anyone want to go and see the Sunday afternoon cockfights? Now I know that lots of people have a problem with cockfighting. I wouldn't want to be slashed to bits by razor-sharp claws, either. But what the heck? I'm not closed-minded... I figured I'd check it out.

After a ten minute walk to an otherwise unremarkable intersection of dirt roads, we came upon a crowd of men and boys sitting in a loosely formed circle. It turns out that the feathered fighters weren't cockerels at all, but kakaliq, which look more or less like pheasants. (Anyone know an English or Latin name for this bird? I think it might be Pallas's Sandgrouse.)

Other suprising observations: the fighting wasn't really all that violent. I mean, there was squaking and pecking and jumping around, but no gouged-out eyes or blood-spurting death throes. In fact, there were no visible injuries at all. The fighting proceeded round by short round, with each owner caging his bird as soon as the lesser fighter appeared to lose its nerve. Also, no betting seemed to take place.

Just a bunch of men, relaxing on a Sunday afternoon, watching fat little birds unsuccessfully try to kill each other.

posted May 21, 2007 at 01:07 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (46)

May 17, 2007

Ratforce3 Xinjiang Alpha Squad, Attack!

The grasslands in northern Xinjiang's Altai Mountains are under attack by determined radical forces bent on death and destruction by any available means to achieve their goal of world domination! Yes, I'm talking about rats... despised worldwide for their ability to destroy food supplies, spread disease, and crawl over sleeping babies in the middle of the night. When trying to route an enemy of such extreme capabilities, the only choice is to call in Ratforce3 Xinjiang Alpha Squad:

Animal husbandry officials in western China have deployed crack forces of trained wolves, eagles and foxes to combat an outbreak of marauding rats, local media reported on Wednesday.

The Fuyun county government in Xinjiang's northern Altai region spent 80,000 yuan ($10,400) buying and training 20 foxes at a special base to catch rats that threatened to destroy some 2 million hectares of grassland.

The exact location of this "special base" remains undisclosed, but fear not citizens! Why, an eagle alone can eat up to ten rats per day.

China trains fighting fox force to rout rodents

16 May 2007

Reuters News

BEIJING, May 16 (Reuters) - Animal husbandry officials in western China have deployed crack forces of trained wolves, eagles and foxes to combat an outbreak of marauding rats, local media reported on Wednesday.

The Fuyun county government in Xinjiang's northern Altai region spent 80,000 yuan ($10,400) buying and training 20 foxes at a special base to catch rats that threatened to destroy some 2 million hectares of grassland, the China Daily said.

"The rat populations in areas where the foxes make their homes are much smaller than in other areas. We plan to train and free 200 foxes into the wild every year," Shayila Wu, a local official, told the paper.

The local army contingent had also set up 50 perches for eagles, the paper said, adding that an eagle could eat about 10 rats a day on average.

The large plains rats, which were posing a threat to local people's livelihoods through environmental damage and disease, had bred heavily due to an unseasonably warm winter, the paper said.

Where rat poison had failed, the natural predators were "expected to come in handy this year", the paper said.

China has a history of using unorthodox means to eradicate pests. Mao Zedong launched the "Four Pests" campaign during the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s, instructing citizens to kill flies, mosquitoes, rats and sparrows.

Pest control efforts included banging pots and pans to scare sparrows into flight and have them eventually drop to earth dead from exhaustion.

posted May 17, 2007 at 11:53 AM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (45)

May 14, 2007

Name That Toxic Substance

Hi boys and girls! Are you ready to play China's favorite guessing game right from the comfort of your very own home? It's... NAME THAT TOXIC SUBSTANCE! [applause]

Contestants, here's your first clue for today's substance: a new apartment - somewhere in China - has been fitted out with new furniture. You know, the glossy-white-paint-over-fiberboard kind. A faucet is left on it that same apartment, creating a minor flood. Everything gets wet, and about ten days later this day-glo orange toxic substance starts appearing on all wood surface that were touched by the flood.

Not sure yet? How about trying to identify the substance in this photo:

Now for the bonus clue: the bed in the apartment, once moveable with ease, is now glued to the floor.

Seriously, folks... can anyone out there tell me what on Earth I'm dealing with here and if I should run like hell?

posted May 14, 2007 at 10:05 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (27)

May 11, 2007

Xinjiang News for 2007.05.11

I know, I know. Despite my promises to shape up, I still haven't been paying much attention to the blog. It's just one of those times in a man's life when activities like blogging are pushed aside by small but annoying hurdles: gearing up for the summer farming season, moving house, getting China Telecom to install an Internet connection. (Yes, I'm going back to China Telecom... but not by choice. The new building I'm living in won't allow China Netcom to install their network lines.) Anyway, here are a few news items from the Xinjiang-osphere that caught my attention this week:

I know, I know. Despite my promises to shape up, I still haven't been paying much attention to the blog. It's just one of those times in a man's life when activities like blogging are pushed aside by small but annoying hurdles: gearing up for the summer farming season, moving house, getting China Telecom to install an Internet connection. (Yes, I'm going back to China Telecom... but not by choice. The new building I'm living in won't allow China Netcom to install their network lines.) Anyway, here are a few news items from the Xinjiang-osphere that caught my attention this week:

Sunday Times: Karamay students died as Party officials escaped fire

When the first flames flared around the theatre's stage, many of the excited Chinese children watching must have thought it was all part of the show.

Within minutes 288 of them were dead, a tragedy that has haunted their parents for more than a decade but was forgotten by many as China began its headlong rush to prosperity.

It is not forgotten any more, thanks to a band of internet campaigners who have exposed the shameful truth: the schoolchildren perished because they were ordered to sit down in their theatre seats so that Communist party officials could leave first. (link)

Xinhua: Spring winds stop trains

At least 2,000 passengers were stranded and at least eight trains were held at two stations in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region as hurricane-force winds of up to 170 kilometers per hour swept the region on Tuesday and Wednesday. (link)

SinoCast: Railways extend to Hotan, Kyrgyz and Kazakh borders by 2010

The regional government reveals nine important railways projects: Jinghe-Yi'ning-Huoerguosi Line, the double track of Urumqi to Jinghe Line, the second line from Turpan to Korla, Kuytun to Beitun Line, the section between Kashi and Tuergate of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway, the Kashi-Hetian Line, and so on. (link)

Xinhua: Dry beavers dying in Altai

The population of beavers in China is about 500, even lower than that of the giant panda. Beavers usually spend winter in nests built in riverbanks where water levels exceed 1.5 meters.

The Altay region had seen little precipitation since last winter and has recorded its driest spring since 1974. The water volume of the Ulungur River is just 60 percent of level at the same time last year. (link)

You can read all of the articles below.

China aghast at sacrifice of 288 pupils

Michael Sheridan, Far East Correspondent

6 May 2007

The Sunday Times

WHEN the first flames flared around the theatre's stage, many of the excited Chinese children watching must have thought it was all part of the show.

Within minutes 288 of them were dead, a tragedy that has haunted their parents for more than a decade but was forgotten by many as China began its headlong rush to prosperity.

It is not forgotten any more, thanks to a band of internet campaigners who have exposed the shameful truth: the schoolchildren perished because they were ordered to sit down in their theatre seats so that Communist party officials could leave first.

The revelations have prompted millions of Chinese to discuss the incident in recent weeks and forced the state-controlled media to acknowledge it for the first time.

The facts were suppressed for more than 12 years until Chen Yaowen, a reporter for China Central Television, posted on his website a documentary that he had made about the disaster but which the censors had banned.

Scant details of the fire, which has come to be known among Chinese as the "12/8/94 incident", were reported by the state news agency and by a few foreign media outlets at the time.

On December 8, 1994, 500 schoolchildren were taken to a special variety performance at a theatre in Karamay, an oil-producing city in China's northwest Xinjiang province.

Most were the best and brightest pupils in their classes, aged between seven and 14, the offspring of well educated Han Chinese engineers and physicists brought in to exploit the mostly Muslim region's natural resources.

After they were seated, a delegation of the city's most senior officials entered to ritual applause and took their seats. The show began.

From the accounts of survivors, it appears that lamps near the stage either short-circuited or fell. The scenery caught fire, then exploded in a conflagration that engulfed the auditorium within a minute or two.

The first few seconds became the most controversial of the disaster. Survivors insist that a woman official immediately stood up and shouted: "Everyone keep quiet. Don't move. Let the leaders go first."

She has since been identified in online articles as Kuang Li, who was vice-director of the state petroleum company's local education centre, although there has been no official confirmation of this.

The teachers obeyed, telling their charges to remain seated. Children who survived recall that everyone was paralysed by fear and confusion as flames and poisonous fumes filled the air.

By the time the dignitaries had filed out, it was too late. Teachers hurried the pupils out of their seats to other exits, only to find that the emergency doors were locked.

"My teacher asked me to run out of the theatre," said Li Xiang, then a boy of 10, "but when I stood up the hall was smothered in smoke and fire. The power then cut out. People could see nothing. The place was full of crying and shouting. I was lucky, as at last I crawled out of the hall."

In their haste to save themselves, a Chinese court later heard, none of the officials had bothered to order the fire exits to be unlocked.

Parents and survivors alleged that Kuang took refuge in a ladies' cloakroom that could have sheltered 30 people and barred the doors behind her.

After the fire was put out, the city's emergency services retrieved the bodies of 288 children and 36 adults.

Most of the adults were teachers who perished alongside their pupils. About 100 of the children's corpses were heaped up outside the cloakroom.

The state media recorded the calamity in dutiful but sparing dispatches. A secret party investigation began. Legal proceedings were started, although no publicity was given to them.

For the bereaved and the survivors, the long years of silent endurance were beginning. In 1995, 300 families of the dead and injured sent representatives to the National People's Congress in Beijing, supposedly the venue for Chinese citizens to seek justice and a fair hearing.

They were led off by security guards to a walled government compound, where five buses were waiting to ferry them back to the airport. The group were then escorted through special channels to a plane bound for Xinjiang.

Chen was filming what he thought would be a hard-hitting television report about official negligence. "Even then, 12 years ago, when I tried to set up interviews with the victims, some refused to talk because they were under pressure. I knew local officials were following me. But I never thought my report would be banned or that the local government would conceal the truth," he said on his website.

According to a new account in the online edition of Nanfang Weekend, a campaigning newspaper, the Communist party was dealing out its own justice. A court convicted 14 people, four of them senior officials, of neglecting their duty and imposed prison sentences of up to five years. Public access to the court was tightly restricted.

Fang Tianlu, the highest ranking official in the theatre, received five years for fleeing the scene, failing to organise the escape of the children and neglecting to alert the fire brigade. Zhao Lanxie, the vice-mayor, and Tang Jian, a city education official, got four and five years respectively. Kuang was given four years.

All 14 were freed within two or three years, however. Fang was allowed to retire with a pension and others have been relocated to other cities. Kuang is said to have rejoined the Communist party and entered the insurance business.

For the survivors, the pain was just starting. The 10-year-old Li grew to adulthood with his face scarred and without his fingers, which had to be amputated from his charred hands.

"I'm now a student at Sichuan University and I can fit in because I'm an open-minded person and a great footballer," he said, "but at first my appearance scared everyone off."

Li Jiang, another victim with facial burns, fell in love but was rejected by his fiancee's parents. He stays shut in his room all day.

Hu Ping, a girl of 10 at the time of the fire, refuses to meet anyone and has vowed never to marry because her hands remain fused and twisted while her legs are scarred by skin grafts. She was offered a university place to read medicine, but could not summon the courage to accept it. Her parents "cry all the time".

"I felt constantly distressed," said Chen. "I believed I should do something to console those innocent souls." Emboldened by the growth of online debate in China -where at least 137m people now use the internet - he posted his material on a website last year.

It opened a door to a long suppressed public outpouring of grief and rage. Parents of the victims and badly burnt survivors of the fire have revealed their sorrow and suffering in extensive online commentaries, prompting thousands of angry internet users to accuse officials of a cover-up.

"Those leaders should have protected children but cared only for themselves," said Gao Liwen, 54, an engineer who lost Xiaoyin, his eight-year-old daughter, in the blaze. "They should have been tried for murder."

The father of a dead nine-year-old, who did not disclose his name, said the Chinese people would never forget the words "let the leaders go first". The government promised a memorial, but never built one, he said.

Families received compensation of up to Pounds 4,000, yet this has failed to purchase any consensus that the case is closed. Instead people are demanding a public apology, commemoration of the dead and proper punishment of the guilty.

These are the kind of demands that are made every year on the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 and which the party considers non negotiable.

Extraordinarily, China's army of censors have not blocked the discussions. Chen believes that the issue of a "pure-hearted" government apology, so important in Chinese culture yet so politically sensitive, explains the huge public interest in the case.

Some Chinese internet users say they were profoundly affected by Chen's interview with Li Ping, 47, a teacher and the mother of 10-year-old Teng Teng, who died in the fire.

Like a traditional grieving parent in ancient times, she still talks to his portrait every day. "I always address my son's photo like this," she says. "My dear son, in this world which you have left, there is one proverbial rule for all, be they white or black, brown or yellow: when danger strikes, let women and children go first.

"It might not be in our constitution or any party document, but it's a basic law of human behaviour. This law broke down that day in our city."

High winds stop train services in China's Xinjiang

9 May 2007

Xinhua News Agency

URUMQI, May 9 (Xinhua) -- At least 2,000 passengers were stranded and at least eight trains were held at two stations in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region as hurricane-force winds of up to 170 kilometers per hour swept the region on Tuesday and Wednesday.

"We'll wait until the wind trails off and visibility improves," said a spokesman at the railway station in the provincial capital, Urumqi.

The Urumqi railway station has canceled four trains, including one to Xi'an in the northwestern Shaanxi Province and three to other parts of the region amid fears that trains might be derailed in high winds in Gobi desert.

This has posed a problem for many holidaymakers who are eager to get back to work after the May Day holiday in the first week of May.

The railway station in Hami, a city in eastern Xinjiang, has also delayed four trains bound for Urumqi.

High winds have been sweeping Hami for five days. The local meteorological station said winds gusted 170 kilometers per hour Tuesday night and would probably ease off Wednesday night or early on Thursday.

Railway authorities in Urumqi refused to comment.

The local civil affairs department said no deaths or injuries had been reported as yet because the affected areas are sparsely populated and have few communication links.

In the cities the weather has been less disastrous, but Urumqi suffered heavy rains on Wednesday.

On Tuesday night, the temperature in the southern suburbs of Urumqi dropped to minus two degrees Celsius, compared with 15 degrees over the weekend. The winds measured 38 kilometers per hour.

Hurricane-force winds derailed 11 carriages of a train in Xinjiang on Feb. 28, killing three passengers and injuring 34 others.

Xinjiang to Extend Railways to 4,000km by 2010

9 May 2007

SinoCast China Business Daily News (Abstracts)

XINJIANG, May 09, SinoCast -- Northwestern China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region plans build new railways of 1,800 kilometers long in the 11th Five-Year Plan period from 2006 to 2010, extending the total length of operating railways to 4,000 kilometers four years later.

The regional government reveals nine important railways projects: Jinghe-Yi'ning-Huoerguosi Line, the double track of Urumqi to Jinghe Line, the second line from Turpan to Korla, Kuytun to Beitun Line, the section between Kashi and Tuergate of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway, the Kashi-Hetian Line, and so on.

In addition, a section of the Lanzhou-to-Xinjiang railway will start electrification reform, and a central container station will be built in Urumqi, capital of the region.

By 2010, the region is estimated to have running railways of over 4,000 kilometers, reaching a railway density of about 25 kilometers per square kilometer, and will have improved the railway passenger traffic and railway freight volume to 14.5 million person times and 72 million tons respectively.

Beavers threatened by drought in NW China

4 May 2007

Xinhua News Agency

URUMQI, May 4 (Xinhua) -- The long drought in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is threatening the survival of the country's tiny beaver population, according to local forestry sources.

In northern Xinjiang's Altay area, low water levels have driven the semi-aquatic rodents from the Ulungur River, their main habitat in China, to look for new homes.

"We have received reports that beavers have died searching for new habitats. Some are killed by dogs and some simply die from thirst," said Han Baohong, director of the forestry bureau in Fuhai County, on the lower reaches of the Ulungur River.

"After the snow has melted in May, the drought will make living conditions even worse," he said.

Some beavers had started digging into the banks of irrigation channels, posing a threat to local agricultural production.

The population of beavers in China is about 500, even lower than that of the giant panda. Beavers usually spend winter in nests built in riverbanks where water levels exceed 1.5 meters.

The Altay region had seen little precipitation since last winter and has recorded its driest spring since 1974. The water volume of the Ulungur River is just 60 percent of level at the same time last year.

The forestry administration has called on residents to help protect beavers. It has also assigned workers to track the animals so they can help them survive.

posted May 11, 2007 at 02:45 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (46)

May 01, 2007

Where There's Hashish, There's Marijuana.

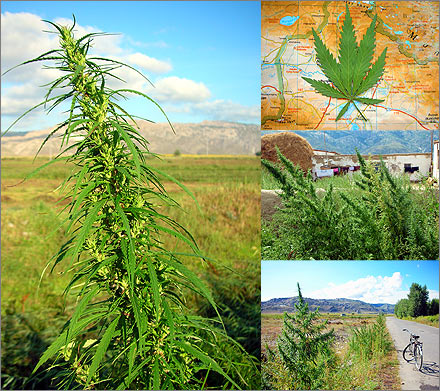

It's no secret to anyone who's been approached by a sketchy Uyghur on the streets of Beijing or Shanghai that Xinjiang is to hashish what Yunnan is to... well, every other illegal controlled substance. Thus it came to be last summer that Marvin Moses — intrepid reporter for High Times magazine — traveled to my fair but remote region of China to track down the holy grail of ganja: the original mother plant from which all later strains of cannabis are descendants. Moses set out to find this ancient lady armed only with a 2,500-year old quote from some "super-awesome Greek dude" named Herodotus:

It's no secret to anyone who's been approached by a sketchy Uyghur on the streets of Beijing or Shanghai that Xinjiang is to hashish what Yunnan is to... well, every other illegal controlled substance. Thus it came to be last summer that Marvin Moses — intrepid reporter for High Times magazine — traveled to my fair but remote region of China to track down the holy grail of ganja: the original mother plant from which all later strains of cannabis are descendants. Moses set out to find this ancient lady armed only with a 2,500-year old quote from some "super-awesome Greek dude" named Herodotus:

The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy.

It turns out that the Scythians of Herodotus' day were inhabitants of the Altai Mountains, where Xinjiang meets up with Mongolia, Russia, and Kazakhstan. It took a bit of searching, but Moses finally found what he was looking for in a beautiful valley near Kanas Lake:

Renting a bicycle from a local resident, I explored the valley for hours, finding marijuana at every turn growing beside houses, in fields, and along the side of the road. The villagers smiled and nodded when they saw me taking pictures, but not once did they ever give any indication that they considered cannabis to be anything but a common weed. I knew, however, that these plants were far from common.

Marvin would sure be happy if you went out and bought the June issue of High Times (ON NEWSTANDS NOW!)... but for all you cheap bastards, the full article is posted below.

Searching for the Mother Plant

High Times Magazine

June 2007

by Marvin Moses

A journey to the birthplace of ganja in China’s wild, wild west.

We all search for marijuana, and we find it everywhere: on the street, at a friend’s house, or in some guy’s sketchy apartment. We find it in small towns and big cities on six continents. It’s as much part of daily life as eating or sleeping. It’s something we live, something we do.

Yet despite the enthusiasm we have for our favorite plant, most of us know very little about marijuana’s basic origins. Who were the first people to smoke pot? When did they first get high? Where is the cradle of stoned civilization?

There are, of course, some popular images: the Indian sadu puffing away at his chillum, or a Nepalese monk hand-rolling temple balls of hashish high in the mountains. But while these images focus on the Himalayas as the source of the original mother plant, experts have also pointed out a different mountain range, 1,500 miles to the north, as the possible birthplace of ganja.

The Altai Mountains are located in the heart of Central Asia, along the borders of four countries not typically associated with the term stoner’s paradise: China, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Mongolia. The mountains bustle with the comings and goings of semi-nomadic sheep and goat herders during the summer, but are nearly deserted during the harsh winters. Located farther from the ocean than any other place on Earth, Altai is a region difficult to get to and seldom visited by foreigners.

Today’s political borders place a good portion of the Altai Mountains in the far-western hinterlands of China. The mountains mark the northernmost point of China’s Xinjiang Province which, in addition to Kazakhstan, Russia, and Mongolia, also borders Kyrgystan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Apart from the mountainous north, Xinjiang is mostly a vast, uninhabitable desert. We’re talking about a place at the ass-end of China, smack in the middle of nowhere. This is where I chose to begin my search.

-----

Along with Tibet, which borders it to the south, Xinjiang (pronounced shin-JEEang) is one of the newest parts of China, an area that experienced little or no control from Beijing before the Communist takeover in 1949. Also like Tibet, Xinjiang is an area not traditionally inhabited by the Chinese majority Han people, but by minorities, many of whom would prefer political independence to their often difficult lives under the watchful eye of a totalitarian government. The natives of southern Xinjiang are a Muslim, ethnically Turkic people known as Uyghurs (pronounced WEE-grs), while northern Xinjiang is home to Kazakhs, Mongols, and Tajiks.

My quest began in Xinjiang’s capital city of Urumqi, a quaint village of more than two million people. “Two million!?!” you may be asking yourself. “That sure is a hell of a lot of people for the ‘middle of nowhere.’” And you’re right – it is – except that you’ve got to remember the massive scale of China and its one-and-a-half billion people compared to, say, the United States. If the city of Urumqi was moved from China to the United States, it would be one of nine American cities with a population of over one million. In China, Urumqi is one of one hundred and sixty-six cities with more than a million people. “Big” means something completely different in China.

Urumqi is a two-and-a-half day journey by train from China’s capital, Beijing. Arriving there, I wasn’t sure at first that I’d be able to find any damayan (marijuana). Like a tourist anywhere, it was difficult to know where to begin looking. As this was China, I also felt the need to be especially careful while seeking out marijuana. There’s no such thing as “too paranoid” or “too cautious” in a country that brutally enforces its strict drug laws, frequently executing smugglers, dealers, and users. Precise figures aren’t available for China, but human rights groups estimate that annually more than five hundred people there are given a bullet-in-the-back-of-the-head for drug-related crimes.

Paranoia aside, it was encouraging when Uyghurs began offering me nisha (hash) as I wandered through bazaars and pool halls in the first days of my search. What’s that old saying? It goes something like, “Where there’s hash, there’s marijuana.” As I sat in a small, dusty apartment passing around the bong with my newfound friends, I knew that I was on the right path.

-----

From Urumqi, an overnight bus takes you to Buerjin, the jumping-off point for the Altai Mountains. As I wasn’t sure whether or where I’d find the wild ganja I was looking for, I decided that I’d have to check out a few different locations in the region. My first investigation would be along China’s border with Kazakhstan.

During the ride to the border, I searched in vain for any trace of marijuana growing alongside the road. Even as we climbed to a higher altitude near the border, the environment didn’t seem right for cannabis. It was all rolling hills covered with low, golden grasses. The only green in sight was the occasional tree that somehow managed to find an underground source of water.

I’d learned from some Kazakhs that even though they don’t puff nearly as much as Uyghurs, many Kazakhs do enjoy rolling up a big joint (or two) when cannabis reaches maturity at the end of the summer. Unfortunately, I’d been too worried about seeming overly interested in marijuana to ask them exactly where I might find the plants.

Arriving at the border, the outlook was bleak. Jimunai is a nothing town between the Altai Mountains and the endless plains that stretch out west over Kazakhstan. It was almost completely empty except for a busload of track-suited Russian tourists. Without a visa, I was stuck in China. After an hour or two spent fruitlessly searching along the fence separating the two countries, I jumped in a cab headed back towards civilization.

-----

If I was going to find any cannabis, it obviously wasn’t going to be located on the high plains. I’d have to head up into the mountains, where there’s more rain and stronger sunshine.

Kanas Lake, a popular destination for adventurous Chinese tourists, is located high in the Altai Mountains near the Mongolian border. It’s dubiously billed as the world’s last unspoiled natural scenic spot, a claim which couldn’t be further from the truth. It certainly is beautiful, with snow-capped, alpine peaks surrounding a long, crescent-shaped turquoise lake. But unspoiled it isn’t; the overpriced hotels and disco yurts blaring Chinese club tunes create a distinctly unnatural environment.

Three thousand years ago, however, Chinese influence on the region was almost nonexistent. At that time, the Altai Mountains were the heart of Scythia, an ancient kingdom whose fierce nomadic warriors fought throughout Central Asia and Northern Europe. Aside from being perhaps the first people to tame horses, Scythians also occupy an odd historical footnote: they are the first recorded potheads. Around 450 B.C., the Greek historian Herodotus took notice of their preferred smoking method:

“The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy.”

In terms of the search for marijuana, Kanas Lake seemed like a step in the right direction. The land around the lake was much more fertile than what I’d found at the Kazakh border. Everywhere was covered in either pine trees or a knee-high blanket of flowers, grasses, and weeds. I hadn’t yet found what I was looking for, but I could almost sense its presence. If people here had been getting stoned in 2000 B.C., reason dictated that some wild plants should still be growing somewhere.

After two unsuccessful days spent walking around Kanas Lake and climbing nearby mountains in search of wild ganja, I decided it was again time to move on. I’d heard about a village in nearby Hemu Valley where the scenery is supposedly the best in Altai. With far less tourists, Hemu is also billed as a relaxing chill-out spot for those seeking refuge from Kanas Lake’s theme park-like atmosphere.

-----

The problem with getting to Hemu was that the road leading there had been put out-of-service for a few days by foul weather. The only transportation option available was to join some Kazakhs who would guide me on horseback. It would be a two day journey through the mountains, but along the way I’d have a chance to see nomadic families travelling with all of their possessions and livestock, as well as some spectacular mountain scenery. I would get to see the region as it had appeared to countless generations of wandering nomads. I’d also be able to view Altai’s plant life at close range, hopefully spotting some elusive cannabis.

Arriving in Hemu Valley, I felt that I’d accomplished quite a lot. Despite having been thrown from the horse and having a painfully sore ass, I’d managed to complete the trip without breaking down in tears. Despite my lactose intolerance, I’d managed to consume a wide variety of rancid-tasting Kazakh milk products (butter, cheese, yogurt, butter tea) without becoming violently ill. Unfortunately, I still hadn’t spotted any ganja. Many of the plants I’d seen along the way appeared to have a very similar structure to cannabis, but they weren’t the real deal. I was beginning to doubt that marijuana still grew anywhere upon the slopes of the Altai Mountains.

Nevertheless, the village was a beautiful place to recuperate for a day. I could finally get a hot, fresh-cooked meal and sleep in a warm bed. The one thing that I couldn’t get rid of was my overall sense of disappointment that my search would soon be over without any success. What had happened to the Scythians’ historic source of marijuana? Had it been eradicated by man, beast, or nature? Would I never get to experience the sweet smell of wild, all-natural cannabis?

-----

It came as shock, then, while travelling back to Buerjin the next morning when I began to spot a few plants here and there with a very marijuana-like appearance. Having been deceived previously while on my horse trek, I discounted the possibility that what I was seeing was actually cannabis. But as the roadside plants became more and more frequent, I couldn’t help but pay close attention. Whizzing by was something that looked a lot like – no, exactly like – my favorite smokeable weed. On the pretence of having to take a piss, I asked the driver to pull over.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of joy that overcame me when I realized that what I was looking at was actually cannabis. And these weren’t just some tiny little sprouts. They were big, fat, healthy-looking plants swaying in the wind, soaking up the high-altitude mountain sunshine. Pinching off a small bud, I found the aroma to be very sweet, but without a lot of the overpowering intensity one often gets from indoor or hydroponic ganja. This was marijuana as nature had created it.

Although I would have loved to frolic for hours along the side of the road, my taxi driver and his other passengers had a different idea. As I had no tent and there were no settlements in the vicinity, I was reluctantly forced to pull a few specimens out of the ground and jump back in the cab. I tried to cheer-up by reminding myself that I had at least confirmed the continued existence of ganja in the Altai Mountains.

-----

With a stroke of luck, however, I got the chance to spend all the time I needed with what might be a direct descendant of the original strain of cannabis. One of my fellow passengers asked the driver to let him off in the small village of Hongqi, located in a huge valley just below the mountains. As we pulled into town, I saw a great swath of ganja growing on the banks of the local river. Knowing that this was probably my one chance to take a closer look, I told the driver that this village would be my final stop.

Renting a bicycle from a local resident, I explored the valley for hours, finding marijuana at every turn growing beside houses, in fields, and along the side of the road. The villagers smiled and nodded when they saw me taking pictures, but not once did they ever give any indication that they considered cannabis to be anything but a common weed. I knew, however, that these plants were far from common. I had finally found what I was searching for: the original mother plant, the birthplace of marijuana.

posted May 01, 2007 at 04:20 PM unofficial Xinjiang time | Comments (72)